Anniversaries and jubilees are central to the formation of cultural memory1 as “monuments in time”.2 They, as well as the commemorative rituals performed on anniversaries, have important functions in the process of memory and identity building by contributing to the transmission, fixation and institutionalisation of identity-securing knowledge within collectives. The past is reconstructed in the present on anniversaries in a way that gives meaning and makes it relatable for the future: the “past” is, as Winfried Müller somewhat crudely puts it, “directed towards one’s own history”.3 This “dressing up” takes place through cultural practices of visualisation, which are simultaneously reinterpretations of the event to be remembered. They are practices of retelling and re-enactment, of medialisation and materialisation, of staging, performing and “curating”.4 Anniversaries and jubilees, says Peter Burke, “reconstruct history or ‘re-collect’ or ‘re-member’ it in the sense of practising bricolage, assembling fragments of the past into new patterns”.5 They order and structure the past, present and future and, thus, have a stabilising effect on society. However, they are characterised by ambivalence. This means that they can also have “a considerable potential for cultural change”,6 especially if they are understood as cultural performances7in the theoretical tradition of ethnological ritual research. In Erika Fischer-Lichte’s words, a performance is initially understood in very general terms as “a structured programme of activities that is performed or presented at a specific time and place by a group of actors in front of a group of spectators”.8These can be events of all kinds, such as “rituals, ceremonies, festivals, games, sports competitions, political events, circus performances, striptease shows, concerts, opera, dance, drama, artistic performances, etc.”.9 If such performances – such as commemorative rituals on the occasion of historical anniversaries – function as cultural performances, they become a “stage on which ideas and interpretations are made visible and vivid and can thus also be made available for social negotiation”.10 This is because these public event complexes are “temporally limited […] situations” in which “goods and values are spread out before an audience in a mostly highly condensed form”, reflected upon and confirmed or questioned.11 Thus, cultural performances as “privileged moments of entry” are particularly suitable “for ethnographic investigations”.12 Using the Berlin Schlossplatz debate as an example, the European ethnologist Beate Binder has made this concept extremely fruitful for ethnological urban research – even against the background of questions of memory culture and historical politics. To this end, she observed numerous cultural performances, such as information events, exhibitions, events, discussion forums, public meetings and protest events, and investigated their role in constituting Berlin’s urban space.13 This conceptual and methodological approach also proves to be insightful in the context of memory research, because it is precisely within the framework of anniversaries and jubilees that “the coexistence of competing patterns of interpretation in processes of change can be made visible”,14 because “the palpability and tangibility of these performances makes them an important venue for political and social conflicts”, according to Binder.15 The visualisation of a plural memory landscape should also be the goal of cultural anthropological memory research, insofar as the (national) anniversaries, which are usually choreographed and decreed ‘from above’, contribute to the homogenisation of the memory discourse and the legitimisation and consolidation of hegemonic structures. It is, therefore, important to understand anniversaries and jubilees as plural arenas in order to also make visible the counter-discourses and suppressed narratives that are produced by memory-cultural staging practices, especially by non-state actors.

Cultural commemorations of anniversaries, especially those of civil society institutions and actors, always have two central characteristics: on the one hand, they have a communal, identity-forming character, as do all social (especially ritual and/or event-oriented) events. Sociologist Regina Bormann writes: “They serve social self-expression, public reflection, sometimes also the design of alternative social courses of action. As collective designs, they serve to communalise, to create a sense of community, of ‘identities’”.16 On the other hand, the forms of cultural memory have an increasingly demonstrative and protest character, especially in the regions of East Central Europe. The cultural performances listed are, thus, also always to be understood as “political interventions in public space”, and are, therefore, simultaneously, “part of social critique”.17 Characteristics such as community building, the exercise of critique and the questioning of prevailing discourses and collective identity offerings come into play especially in times of crisis and upheaval, they have, thus, been described by Victor Turner as “phenomena of the liminoid”. Such phenomena can be identified – analogously to “phenomena of the liminal” that exist(ed) in pre-industrial societies – in complex, late-modern societies that are characterised by diversity, plurality and fragmentation:18

Liminiod phenomena emerge away from the central economic and political processes, at the margins, in the interstices and gaps of central institutions – they have a pluralistic, fragmentary and experimental character. [… they] are often part of social critiques or even revolutionary manifestos – books, plays, paintings, films, etc. that denounce the injustice, inefficiency and immorality of economic and political structures and organisations.19

Bormann has harnessed Turner’s concept of the liminoid for the study of urban experiential spaces. She describes the urban spaces marked (if not produced) by consumption and events as “zones of the liminoid”, i.e. as “stages of cultural performance where the possibilities and limits of society are playfully tested, explored, negotiated or discarded”, as places “where the existing can be examined and the new imagined”.20 In the following, the performative production of such urban “zones of the liminoid” and their function as instances of social control with the potential for mobilisation and change will be examined based on selected cultural performances in the context of historical anniversaries in the Czech Republic. The focus of the study is the so-called Velvet Carnival in Prague, a commemorative event on the anniversary of the “Velvet Revolution” based on the Basel carnival, which is characterised by a highly socio-critical impetus and sees itself as a counter-hegemonic actor. It is founded on ethnographic research, particularly participant observation, photographic documentation, dense descriptions and media analyses of the commemorative events on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the “Velvet Revolution” in 2014.21

The discursive framing: The “Velvet Revolution” in the national culture of remembrance

Although the so-called “velvet” or “soft” revolution (sametová revoluce), which brought down the communist regime in Czechoslovakia in the autumn of 1989, has a national holiday in both the Czech and Slovak Republics, this event remains a place of remembrance ‘from below’.22 According to historian Muriel Blaive, the “revolution” is even a “non-lieu de mémoire” politically and in terms of society as a whole, as it is neither suitable for creating myths and legitimising existing power relationships in terms of identity politics, nor for constructing an overall national sense of unity.23 A central reason for this is a politics of memory that, on the one hand, interprets communism as a foreign implant, “as a historical distortion, an interlude, an aberration from the supposed natural past of national history, an ‘Asiatic despotism’ imported from the ‘East’”.24 This is reflected, for example, in the research mandate of the national authority Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes (Ústav pro studium totalitních režimů – ÚSTR), “which is to address the legacy of the Nazi occupation and the dictatorship of the KSČ (Komunistická strana Československa – Communist Party of Czechoslovakia)”, as well as in the “research into the period 1938–1989, which is defined by law”.25 The institute, thus, ranks the period of communism “among the other totalitarianisms of the 20th century”26 and contributes significantly not only to externalising this period, but to telling it as a story of oppression by major enemy powers. This narrative is legally supported by the controversial “lustration laws”27 of the early 1990s, which define the pre-complaint regimes as “unlawful and criminal”.28 The laws are problematic in several respects: on the one hand, there is insufficient differentiation between “perpetrators” and “victims”, because they also pillory those people who did not necessarily belong to the regime’s henchmen, such as numerous members of the “grey zone”, i.e. people who were active in the official structures but, at the same time, supported dissent.29 On the other hand, however, a number of communists from the nomenklatura have not been prosecuted at all. On the contrary, many of them are among the beneficiaries of privatisation. The lustration laws have not always been implemented, which means that a change of elites has not taken place in all institutions.30 In addition, there has been the growing strength and entry into parliament of the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (Komunistická strana Čech a Moravy – KSČM), the successor party to the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (Komunistická strana Československa – KSČ), a party that has so far not undergone any reforms and, to this day, clings to the legitimacy of the past regime, which was characterised by a gross disregard for human rights. This is an important reason why widespread resistance is forming on the anniversary of the “Velvet Revolution” on 17 November and a change in the politics of remembrance is being demanded. It is, therefore, not surprising that the majority of urban stages on this day are occupied by civil society actors – student initiatives, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), associations, artists and other memory activists – while the state is increasingly withdrawing from public space.31 The commemoration events, which are staged bottom-up by civil society actors, are, therefore, also and especially an expression of a political will to influence and a critical public.32 The occupation of public space and demand for a different politics of remembrance, for a “decommunization” (dekomunizace) of state and society, are important building blocks in this memory building. At the same time, the commemoration of the “Velvet Revolution” and the admonishing memory of the victims and crimes of the communist regime serve as a foil on which many other grievances in politics and society are made visible. These notably include the high level of corruption, discrimination against minorities, the power of the economic elites, problems of environmental pollution and, time and again, the political culture. The latter has been under particular rebuke since Václav Klaus replaced Václav Havel in the office of president in 2003 and even more so since Klaus’ successor Miloš Zeman took office (in 2013). Zeman is highly polarised: while he is popular among former communists, people in rural, structurally weak regions and those in precarious social milieus, opposition to him is forming especially in the intellectual academic urban milieu, which is also reflected in critical media coverage (especially in Lidové noviny [People’s Newspaper] and Mladá Fronta Dnes [Young Front Today]). The reasons for this are mainly Zeman’s populist and Russia- and China-friendly policies (at least until Russia’s war against the Ukraine), his vulgar and often tasteless political style and his broad support within the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (KSČM).33 Moreover, criticism of the “lack of decency in politics” has continued to rise since the election of Andrej Babiš as prime minister (until 2021). Thirty years after the fall of the Iron Curtain, up to 300,000 people have taken to the streets against the two office holders in Prague alone. Doing memory in the Czech Republic is, therefore, primarily associated with doing civil society and doing democracy.

Nevertheless, it should also be taken into account that only certain sections of society inscribe themselves and their interpretations in the urban (memory) spaces. On the one hand, the civil society actors belong to the successor generations of the “Velvet Revolution”, i.e. today’s 20- to 40-year-olds. They are often the children and grandchildren of former dissidents or the children of those young people (especially from the student milieu) who took to the streets in 1989 in their hundreds of thousands. On the other hand, many of them come from urban academic milieus. They are citizens who generally have a high level of cultural, social and, in some cases, economic capital: students from various disciplines and universities and their families, NGOs and civic initiatives, and representatives from the fields of culture and art. They are memory activists who are competent enough to take on the role of an authority regulating the state and the market, or are able to interpret the messages of the organisational elites ‘correctly’ and communicate them through their own networks.34 Sections of the population who do not have such capital, count themselves among the losers of the system transformation and are politically more on the left or right fringe, on the other hand, are not represented or they have their own rallies and try to disrupt the commemorative events of civic initiatives. These are, for example, supporters of the KSČM and right-wing or extreme right-wing groups.35

It has become clear that on the anniversary of the “Velvet Revolution” in the Czech Republic, large sections particularly of civil society are occupying the public space in order to remember the events of 1989, recall the crimes of the communist regime, commemorate the victims and criticise what they see as a failed politics of remembrance. On the other hand, they aim to draw attention to problems in politics and society, question claims to hegemony and demand participation in political decision-making processes. At the same time, in the sense of late-modern experience orientation, the actors are concerned to let doing memory and doing democracy take place in a unique event that appeals to all the senses – especially in order to mobilise the younger generations for their own interests. Thus, a diverse and colourful repertoire of (remembrance) cultural practices is spreading on the urban stages on the anniversaries: vigils, light chains and (open-air) exhibitions commemorating the victims’ experiences of violence and calling for “never again communism”; politically motivated street festivals, flash mobs, carnival parades and re-enactments; readings, concerts, panel discussions and theatre; protest events of all kinds, mostly demonstrations for but, above all, against members of the government, as well as radical right-wing rallies that extend to violent excesses by neo-Nazi groups.36

These initiatives and events have been particularly prominent in recent years: the Sametové posvícení (literally “Velvet Church Fair”, usually translated as “Velvet Carnival” or “Prague Carnival”), founded by the academics and artists’ initiative FÓR_UM in 2012, an association of various NGOs whose members explicitly model themselves on the Basel Carnival and carry their causes into the centre of Prague in carnivalesque costumes. A more detailed description and analysis of these carnival-like commemorative and protest practices follows on the next few pages. It is also worth mentioning the all-day street festival Korzo Národní (Parade on the National Street) organised by the NGO Díky, že můžem! (Thank you that we can!), one of the most diverse and crowd-pleasing events initiated by a small group of students in 2014.37

Other actions initiated by various NGOs and associations in recent years which have (had) a high mobilisation potential and have also received or experienced great popularity in the media were, for example, the re-enactment or “reconstruction of the velvet parade” 38 of 17 November 1989 on the 10th and 20th anniversaries in 2009 and 2019 – actions through which the rebirth of civil society was to be re-enacted above all.39 Once again, in 2014, the initiative Chci si s vámi promluvit, pane prezidente (I want to talk to you, Mr. President) initiated by Martin Přykril, a member of the Prague indie band The Prostitutes, caused a sensation by demonstrating against the incumbent president Miloš Zeman with their media-effective actions Červená karta pro Miloše Zemana (Red Card for Miloš Zeman) and Pochod na hrad (March on the Castle).40 And to celebrate the 30th anniversary, the commemorations joined a long line of protests calling for the resignation of Miloš Zeman and Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, who has been proven, inter alia, to have funnelled EU funds into his own pocket and worked in state security.41 All these actions have been attended by anywhere from about 10,000 (re-enactment of the 17 November 1989 demonstration on 17 November 2009) to more than 250,000 people (Demisi! [Resign!] demonstration on 16 November 2019) in recent years.

The Velvet Carnival will be the focus of attention in the following. Firstly, we will look at the actors and their practices and motives for shaping the anniversary. Then, this urban phenomenon of the liminoid will be examined in the context of larger processes of social transformation.

The Velvet Carnival as an urban zone of the liminoid

The Velvet Carnival can be defined as a ritualised cultural performance imported to the Czech Republic and adapted to local traditions42 as an invented tradition brought about by migration and globalisation processes, which in recent years has become an important part of Prague’s culture of remembrance ‘from below’. It was initiated in 2012 by the FÓR_UM initiative, which emerged from an interdisciplinary project by theatre scholars and performance artists on the topic of “Satire in Public Space”.43 One of the initiators, the religious scholar and performance activist Olga Věra Cieslarová (*1980), developed the idea of transferring the Swiss custom, or individual elements of it, to Prague in the course of her research on the Basel Carnival and to establish a “Prague Carnival” in the context of the “Velvet Revolution” on 17 November.44 According to Cieslarová when she started the collaborative project, there were no actions in the Czech Republic on the anniversary of the “Velvet Revolution” that were communal and promoted democracy. On the contrary, violent protests would increase on 17 November. Therefore, there should be an alliance of civil society initiatives (e.g. for the reappraisal of communist crimes or for equal opportunities and against discrimination), non-profit NGOs (e.g. environmental organisations such as Greenpeace or Extinction Rebellion) and artists from the fields of visual arts and music, who together open a public space for reflection, providing “a platform for a broad public discussion”.45 The primary aim of FÓR_UM is to “support playfulness and creativity in the formulation of serious social and political issues” and to “raise awareness of social issues and values”,46 for which the forms of satire and carnival are better suited than banners. “Following the Basel model”, the aim was to “support democracy in the Czech Republic with satire and art” and promote “free, creative and democratic citizenship”.47 “Satire and the ability to reflect” are particularly necessary today because they are the “most effective defence against populism, demagogy and totalitarianism of all kinds”.48

The participants develop their “subjects” in joint workshops every year, similar to the carnival cliques in Basel, and translate them into carnivalesque-satirical forms. The city provides vacant rooms for temporary use, which the participants first convert into workshops (dílny) where the “larvae” (masks) and costumes are designed and produced and the pamphlets are printed. Around 17 November, these will then become the “velvet centre” (sametové centrum), where readings, panel discussions and art performances will take place. The terms and theoretical programmes that FÓR_UM uses as a guide, as well as the forms of expression and practices that it employs, make the deliberate reference to various customary traditions, especially those of the Basel carnival, unmistakable: there are the themes, motifs or materials known as “subjects”, which are processed in a carnivalesque way and made available to the public for consideration. The “subjects” are transmitted via the communication medium of the “entertaining pamphlets”, as the organisers call their satirical-political information flyers and brochures, i.e. the political pamphlets that point out grievances in politics and society and call for them to be fought against. Then there are the masks, reminiscent of the “larvae” of the Basel Fasnacht, but also of the masks of the Comedia dell’arte and the Carnival of Venice, and costumes like those worn in circus arenas and jugglers’ performances. Some of the disguises look very professional, while for others their designers make do with simple materials, such as painting egg and shoe boxes or working with crepe paper, old bedsheets and (plastic) rubbish. The Middle Ages are just as present in the form of knight, executioner and clergy costumes as are abstract arts and artificial intelligences of the 20th and 21st centuries. Music, as in all well-known carnival, Fasching and Fas(t)nacht traditions, is an important element that accompanies the procession. The repertoire of genres at the Velvet Carnival ranges from Basel Guggenmusik and flute music to Latin American samba sounds, pop, hip-hop, Schlager and folk songs from the national and international music scene. Some “cliques” are led by individual musicians, others have an orchestra with them, and a few do without any musical accompaniment at all. This blend of elements from different customs points to the underlying hybridity of the Velvet Carnival. In addition to its outward appearance, it is also evident in its functionality: the Velvet Carnival is both an art and theatre production, it is a celebration and ritual, a party and event, an information and educational platform. This ambiguity in terms of form and function also reveals the impossibility of committing oneself terminologically to this kind of postmodern “custom”. If one were to follow the older German-language research on customs here, the German designation “Prager Fasnacht” would be preferable to the designation Velvet Carnival – especially since the Velvet Carnival is explicitly based on the Basel Carnival. Werner Mezger distinguishes between carnival and Fastnacht as follows:

In simplified terms, the two customs can be summarised in the following pairs of opposites according to their different manifestations: carnival versus Fastnacht, that is costume versus disguise, cardboard nose versus wooden mask, spontaneity versus ritual, frivolity versus melancholy or, to put it a little more pointedly, wine bliss versus beer seriousness.49

However, if one takes a closer look at the cultural performance in Prague, such a dichotomy cannot be maintained, because elements of both categories of customs can be found, as well as elements from other traditions. Due to this bricolage-like composition and in view of the semantic charge of “velvet”, the translation “Velvet Carnival” seems to make the most sense.

Against the background of this initially general definition and theoretical positioning, the Velvet Carnival will be described in more detail based on concrete questions: Who are the civil society actors hiding behind the masks? What subjects are transported through them into the urban space and into the everyday lives of the masses? How are the subjects staged discursively and performatively? And how can the Velvet Carnival be placed in wider social contexts?

The Velvet Carnival took place for the first time in 2012. Six “NGO cliques” together with five artists created 150 masks on a volunteer basis, at a cost of just under 1,000 euros. One year later, there were already more than twice as many cliques and the costs amounted to over 11,000 euros.50 At the beginning particularly, the carnival pioneers in Prague were also supported by artists from Basel, who assisted in the making of the “larvae” and accompanied the procession with their flute playing (which individual cliques from Basel still do today).51 During the period of my research in 2014, there were more than 15 cliques, 21 artists and 8 dramaturges who offered a cultural programme in the city for one month after the parade on 17 November. The costs, largely raised by sponsors, are said to have amounted to about 25,000 €.52

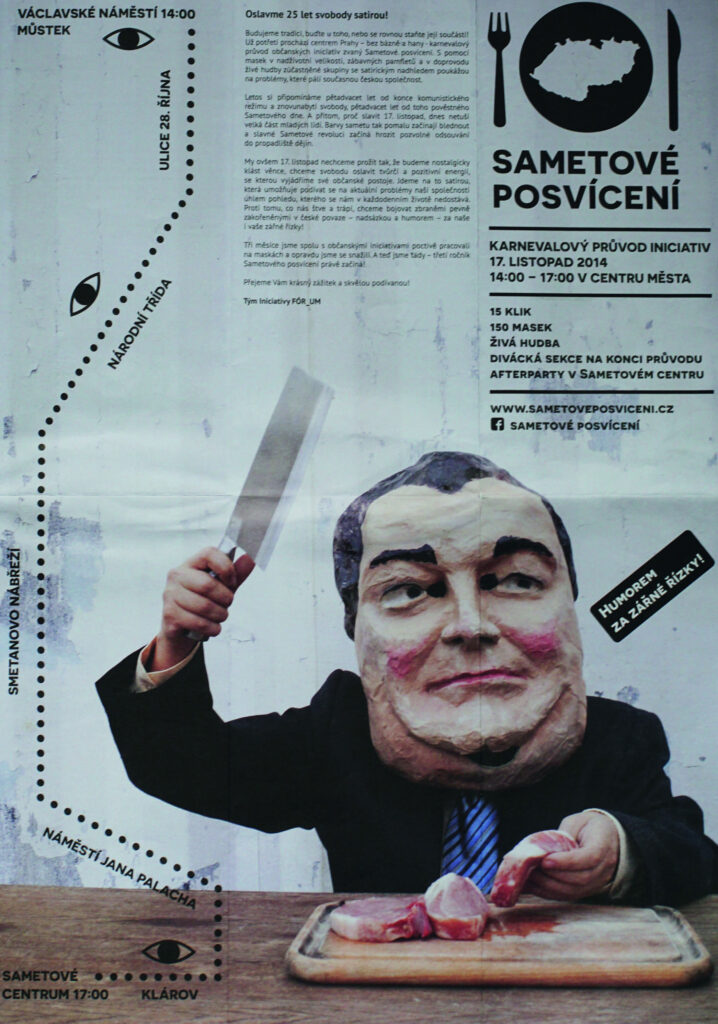

In accordance with the Czech meaning of the word “Church fair” (posvícení), the logo of the carnival forms a place setting with a plate, knife and fork (Fig. 1). The geographical silhouette of the Czech Republic is depicted on the plate, reminiscent of a breaded schnitzel – one of the most popular dishes in the Czech Republic. The logo, thus, ironically alludes to the motif of celebration and pleasure, of eating and drinking before the (meatless) Lenten season, and simultaneously links it to the objectives formulated to bring grievances to the table. Every year, a new motto is added to the logo, which, as in Basel, reflects current discourses. The topics in previous years have included a failed culture of remembrance and commemoration (2012),53 domestic government crises (2015),54 Fake News (2017),55 bee deaths and climate change (2019).56 In the anniversary year 2014, 25 years after the fall of the Iron Curtain, the motto was “With humour for the enlightened schnitzel”.57 The flyer was decorated with the likenesses of allegedly corrupt politicians and entrepreneurs preparing and eating a schnitzel. The A3-sized information leaflet, which announced all participating cliques with texts and pictures, said among other things:

We do not want to spend 17 November nostalgically laying wreaths, we want to celebrate freedom with creative and positive energy expressing our civic positions. […] We want to fight against what annoys and torments us for our and your enlightened schnitzel with weapons that are firmly rooted in our Czech essence – with hyperbole and humour!

This brief text summarises what the cultural performance stands for: on the one hand, it aims to create a civic alternative to common commemoration and protest formats and establish a counter-design to existing cultural practices of remembrance. On the other hand, the aim is to “fight” against grievances. However, especially against the background of increasing violence on 17 November in the streets of Prague (as well as in Brno and other larger cities), this struggle should be peaceful, creative, humorous and open to all. Indeed, the Velvet Carnival seemed friendlier, more open, relaxed and joyful than any of the commemorative events I attended on 17 November 2014 (as well as in other years). Nevertheless, attitudes were also very clearly expressed here and social concerns were called for with visible and quite confrontational and unsettling means (e.g. through the use of prisoners’ costumes). However, masks, puppet theatre, music, dance, confetti and especially the presence of lots of children among the participants and spectators contributed to the perception of this “velvet” performance as a colourful and friendly celebration. On the occasion of the milestone anniversary in 2014, 15 cliques took part, whose concerns can be roughly categorised as follows:58 social justice and the struggle for recognition and participation; environmental and animal protection; and criticism of political decision-making processes and corrupt economic practices.

A number of NGOs and initiatives that advocate for the needs of disadvantaged families, especially children and young people, such as Člověk v tísni (People in Need), appeared with the slogan “Where to go with them?”. Or also: “Edudant and Francimor want to go to your school”, which called for the inclusion of children and young people with physical and mental disabilities in mainstream schools. The subject was staged as a small play that addressed negative prejudices against mentally disabled children anchored in society. The practices of discrimination were represented by a teacher who elevated “smart kids with high foreheads” and blond hair to the norm, while bullying those with red hair and crooked teeth (Fig. 2). The accompanying pamphlet, entitled “A weekday morning in the school street in an average Czech town”, featured a corresponding scene with two pupils and the headmaster of a mainstream school. The two boys Edudant and Francimor, one of whom suffers from Asperger’s syndrome and the other is of below-average intelligence, very fat and has dyslexia, dream of going to a mainstream school like “normal” children. But they fear that they are not “normal enough” and “too conspicuous”. An impression that comes true when the headmaster chases the two boys away towards a special school.

Another association, the Nízkoprahový klub Husita (Low-threshold Club Husita), founded by members of the Hussite Czechoslovak Church, again addressed the stigmatisation of children and young people from socially precarious family backgrounds in the Žižkov district of Prague, a former working-class neighbourhood increasingly affected by gentrification measures. The initiative’s flyer was printed with simple bird motifs, mainly doves, and the message “We are rushing to help” (in Czech: “We are flying to help”) and folded into a paper aeroplane. The activists wore bird masks in the style of commedia dell’arte and held oversized birds, reminiscent of vultures, on sticks in their midst. Another NGO pointing out state and societal stigmatisation and discrimination was Tosara (Romani: The Morning). Tosara is a very active association founded by students of Romany studies that provides educational and recreational services for children and young people, mainly from Roma families, who are affected by neglect. In 2014, the subject referred to the discrimination of Roma in educational institutions, the motto was: “They sent me to a special school because I’m Roma. Isn’t that stupid?” More than half of the children in special schools have a Roma background; in some regions Roma make up 80 % of the pupils in special schools. While the student performers wore simple eye masks and walked “voluntarily” in front of the university building made of white cardboard, the heads of the “special needs students” were completely covered with masks and the students themselves were chained to an upside-down special needs school.59

Other NGOs and associations, in turn, addressed the increasing homelessness in the city (“Every city has the homeless it deserves”), inadequate rehabilitation measures for former prisoners (“The real prison starts when you’re out and nobody gives you a job”, Fig. 3)

or demonstrated for renewable sources of energy, against factory farming and for a (capital) city with sufficient green spaces and children’s playgrounds, markets, organic food shops and vegetarian or vegan restaurants. Still others denounced corruption and tax scandals, drew attention to discrimination against LGTBQ movements by the churches (“Even warm pigs go to heaven”) or autocratic regimes in other parts of the world. The latter included, for example, the protest movement Pražský Majdan (Prague Maidan), which emerged in September 2014 as a reaction “to the lax attitude of the Czech president and government to the situation in Ukraine”.60 Under the slogan “We have a small tent – Maidan”, the activists critical of Moscow protested symbolically against Russia’s aggressive Ukraine policy within the framework of the Velvet Carnival: a yellow tent decorated with motifs of Ukrainian traditional costumes (so-called Vyshyvanka motifs) and the flag of the EU, and demonstrators with yellow and blue hair wreaths drove the Russian bear, alias President Vladimir V. Putin, before them (Fig. 4).

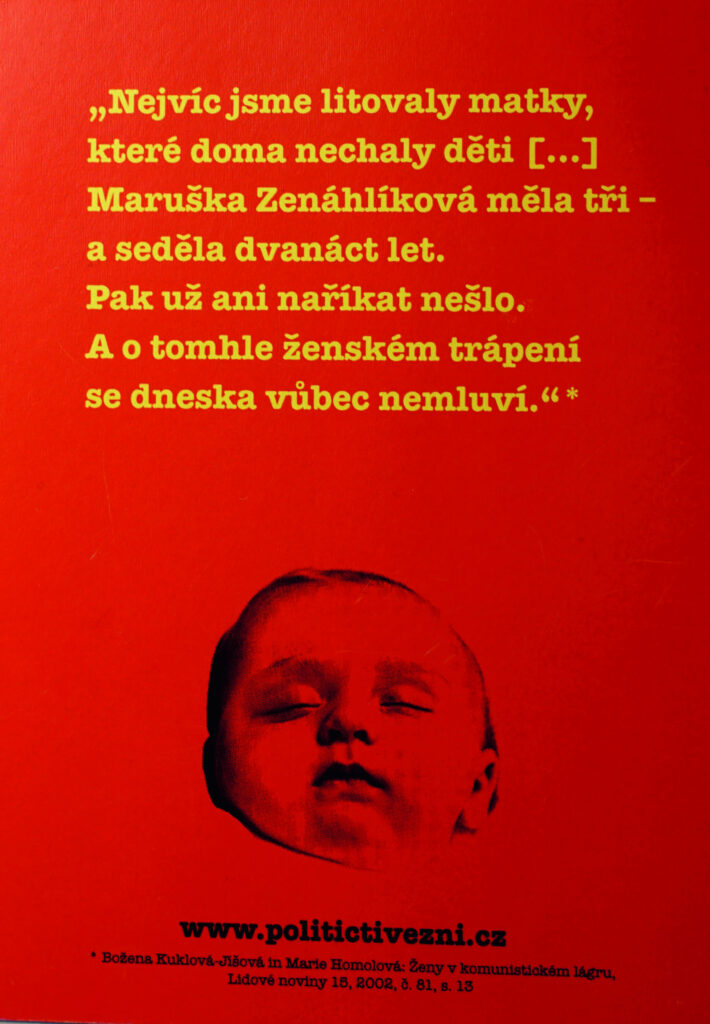

The NGO most directly related in 2014 to the event of the “Velvet Revolution” and remembering the repressive policies of the pre-transition regime was Političtí vězni.cz (Political Prisoners.cz), a digital oral history project “that aims to ethically capture and preserve the memories and life experiences of former political prisoners – eyewitnesses and actors of historical events that were meant to be forgotten”.61 The activists and researchers conduct mainly oral history interviews and make them available to the public on their website. In 2014, women and their children in the communist labour camps of the 1950s, for example, in the Vojna uranium mine, were the focus of the Velvet Carnival under the slogan “They were there too!”. According to Političtí vězni.cz, the history of repressed women, especially mothers, is a topic that is still taboo and has been insufficiently dealt with so far. The participants were dressed as female camp prisoners in grey suits and their heads covered with scarves; they rolled a red star with babies’ faces painted on it in front of them in a pram that resembled a cage (Fig. 5). The face masks or “larvae” gave an emaciated, injured and agonised impression. The group was accompanied musically by a trumpet player wearing a black balaclava. The pamphlets, written in Czech and English, were designed in the form of red postcards with the face of a sleeping baby on the front, and above some of them were moving quotes from interviews with imprisoned women or from their autobiographies. The writer Božena Kuklová-Jíšová (1929–2014), who was sentenced to twelve years in a labour camp in 1954, was quoted as saying: “We felt most sorry for the mothers who had left their children at home […] Maruška Zenáhlíková had three and served twelve years. With something like that, you could no longer even complain. And this suffering of women is not talked about at all today” (Fig. 6).

And on another one it said:

In the beginning, when they [the guards] came to the cells individually, they molested us. But when some of the women became pregnant, they were ordered to come in pairs. The women were in a dreadful situation. One was very afraid to tell her husband about the pregnancy. It was a struggle for values. To have an abortion was a great sin. But in such a situation, it was something else. Arrested mothers simply had their children taken away from them and in many cases gave them up for adoption, so that the woman concerned would never find her child again.62

Although the Velvet Carnival was all about entertainment, parties and events, the critical impetus was omnipresent: dealing with the communist legacy and the crimes committed by the communist regime between 1948 and 1989; current corruption and distribution struggles; education policy, social discrimination and disintegration; environmental and climate protection – socio-political concerns that, with varying degrees of importance, are currently being expressed on the streets and made available for negotiation by civil society actors all over Europe and beyond. In contrast to other forms of protest and memorialisation in the Czech Republic in recent years, such as mass demonstrations (here the march on the castle in Prague or the red card against Zeman), which place a theme at the centre of the performance (in 2014 it was particularly Zeman’s political style), the Velvet Carnival makes it possible to bring different subjects into the public sphere and make a variety of grievances visible. It seems to be a suitable platform not only for NGOs that already have a high profile, such as Greenpeace, but especially for smaller initiatives that rarely attract media attention and do not have prominent advocates, for example, FÓR_UM with its cultural performance offers the opportunity to stage their own concerns on the urban stage. The Velvet Carnival gives socially marginalised people the opportunity to become part of a critical public sphere. By giving “oppressed” people space to occupy central and historically significant places in the city (e.g. Wenceslas Square, Charles Bridge and the National Street), it “contributes to the ‘empowerment’ of socially disadvantaged groups […]”.63 The carnival does this by means of satire and the grotesque, with humour as a “weapon of the weak”,64 by having the rulers – in this case Zeman, Putin and corrupt entrepreneurs – appear in the form of exaggerated, grotesque bodies made of papier mâché, wood, plastic waste or metal objects, and by reversing the roles between ‘above’ and ‘below’, between the hegemon and the oppressed (e.g. the Maidan drives the Russian bear before it). Alongside oppressive, serious subject productions, such as those of former political prisoners, a topsy-turvy world is brought onto the stage – very much in the style of François Rabelais (or in his reception by Mikhail Bakhtin) – and laughter is placed at the centre as a practice of resistance.65

The Velvet Carnival is a hybrid, polyvalent phenomenon in a late modern society. First of all, it is an event to remember the upheavals of 1989, to commemorate the “velvet” end of the repressive regime under the rule of the Communist Party and the regaining of democracy. Regarding the how, i.e. the praxeological design of the anniversary, the initiators are concerned to distinguish themselves from conventional remembrance rituals, such as wreath-laying ceremonies, and to create new commemorative practices. This is done by explicitly adapting elements of the Basel carnival: such as socio-political subjects, masks and “larvae”, pamphlets, music, confetti and the parade. The commemorative procession is, thus, also and above all a carnival or Shrovetide procession that deals with social issues in a satirical way. In this function, it can be described as a tradition newly established by civil society actors, as a “hybrid new construction”66 that is composed bricolage-like of different building blocks and that satisfies different needs and fulfils different functions. Humour and wit, satire and creativity as the guiding motifs of carnival and Fasnacht are linked here with the demand for unconventional, but above all peaceful rituals, especially against the background of the increasingly “aggressive demonstrations” on the occasion of the anniversary celebrations on 17 November. According to the initiators, they want to counter this development with something “cheerful”, “humorous” and “intelligently critical”,67 they want to “transform anger into creativity”.68 Here, FÓR_UM follows the global trend of recent years to replace confrontational forms of protest, violent ones at that, which often deterred interested parties and ran counter to mass mobilisation, with new, creative, playful and thus communicative and inclusive forms. Sonja Brünzels writes about this in connection with the often carnivalesque practices of the Reclaim the Streets movement – a movement that emerged in Britain in the 1990s as a reaction to the displacement of the population from the inner cities to reclaim public space creatively and with fun: “Carnival [is] initially inclusive – its pull is strong enough to blur boundaries between actors and spectators, above and below, good and evil. Protest, on the other hand, is confrontational and exclusive – it separates the good from the bad, the accusers from the accused.”69

Secondly, the Velvet Carnival offers participating civil society initiatives the opportunity to articulate concerns and demands to the public in a media-effective way, to provide knowledge about social shortcomings and injustices – for example, in the school system, in relation to the social fabric, in (remembrance) politics and the economy – and to propose alternative life and social models (e.g. inclusion, sustainable economy). The cultural performances are, thus, on the one hand, the stage on which very different (interpretations) are staged and different collective identities are reflected and presented. Instead of identities “that cannot be fully lived out in everyday life”, it is more a matter of “exaggerations and expulsions of identity elements that are suppressed by hegemonic cultural tendencies”.70 On the other hand, as a form of protest, they are a “resource of the powerless”,71 since they are about the creative occupation of public spaces. FÓR_UM sees itself as an important civil society actor with an educational and enlightening sense of mission, committed to not only “influencing civil society engagement” but also “spreading good humour”.72

The “‘preparation’ phase” of the carnival in particular would help to “connect members of different social classes” and, thus, “help to cultivate civil society”.73 It is about creatively participating in the shaping and negotiation of society. This cultural performance also fits into the global trend of appropriating urban spaces through creative action, helping to shape them and intervening in them through performative artistic acts.74

Finally, the Velvet Carnival promises experiences and events, entertainment and pleasure: on the one hand, as an end in itself (“We create a good mood”), on the other hand, to generate positive emotions (“When people see this, they associate November with something good and valuable that should be protected”). The cultural performance on the occasion of the anniversary of the “Velvet Revolution” is a popular cultural event that promises an aesthetically pleasurable experience, which is also an important motive for mobilising the participants and the mass media. The satirical street parade, inspired by the Basel Fasnacht, is an event that promises to satisfy individual and collective cravings for fun and (self-)staging, for communalisation and identity. It is an event that, like any other, has to assert itself over and over again in the (media) public sphere and fight for its position on the civil society experience market, which is also a history market throughout (East) Central Europe in November.

The Velvet Carnival can, therefore, be summarised as a liminoid cultural performance that is characterised by hybridity, polyvalence and polyfunctionality. Liminoid because – to echo Turner – it emerged “in the interstices […] of central institutions”, has “a pluralistic, fragmentary and experimental character” and as “part of social critique […] denounce[d] the injustice, inefficiency and immorality of economic and political structures and organisations”.75 However, the extent to which it can actually contribute to overcoming the boundaries of milieus and reach a large number of citizens must be critically questioned, as the actors are primarily members of the educated middle classes. Although a perception of the Velvet Carnival as an elitist event in the capital cannot be ruled out, the cultural practice of the carnival seems to be more accessible and open to broad sections of the population compared to wreath-laying ceremonies, panel discussions, demonstrations and the like.