The systematic exclusion of Jewish scholars and scientists from teaching and research arguably had graver and longer-lasting consequences than any of the Nazi regime’s other political interventions into research and higher education in Germany.1 Its quantitative and qualitative dimensions have only come into clear view as a result of in-depth studies, undertaken in the last two decades, that have reliably established that around a fifth of the teaching staff at German universities and other research institutions were dismissed or compelled to resign from 1933 onwards and that 80 percent of these dismissals were racially motivated.2 It can be assumed that 1,200 lecturers were affected.3 The unfolding of these developments in the non-university sector is particularly well charted. The dismissal of around ninety “non-Aryans” from the Kaiser Wilhelm Society has been described in detail, drilling down to the level of individual fates,4 and the same is true for the approximately thirty committee members of the Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft (Emergency Association of German Science) who were hit by these measures.5

The state of knowledge regarding the academies of sciences and humanities is not quite as satisfactory. Because the institutional ties binding these scholarly communities are comparatively loose, they have generally shown limited interest in tracing their own histories. Nevertheless, at least all the relevant names have been compiled for the academies, as well. The Leopoldina deleted around ninety names from its long list of members.6 The considerably more exclusive academies in Berlin, Vienna, Leipzig, Munich, Heidelberg, and Göttingen each shed on average one to two dozen full and corresponding members.7 In total, the German academies lost around 10 percent of their full members and 5 percent of their corresponding members.8

The fact that most of these deletions of names took place in or after 1938 could give one the impression that the Gleichschaltung of the academies—their “synchronization” with Nazi ideology—took place at a relatively late stage.9 The most spectacular case of all, the resignation of Albert Einstein, the genius of the century, from the Prussian Academy of Sciences and Humanities on March 28, 1933, and from the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities on April 21, 1933, has come be routinely regarded as something of a chronological outlier despite both its clear connection to that context and its significance—in the words of one authoritative expert—“as a portent of the initially voluntary and then forced exodus of Jewish scholars that would soon commence.”10

Astonishingly enough, the events surrounding Einstein’s decision have never been precisely described and analyzed, even though they harbor significant potential for highlighting the stances both academies adopted on the Nazi seizure of power. That explains why considerable space is devoted to Einstein’s resignation from the Prussian Academy of Sciences and Humanities in the documentation prepared by that association’s successor in East Berlin to mark the centenary of Einstein’s birth in 1979—naturally with the foregrounding of class struggle aspects that was de rigueur at the time. This documentation drew on both archival records relating to Einstein’s resignation and the personal memories of those involved, which Max von Laue recorded for posterity in 1947.11

While this made it possible to form an impression from the sources of what took place at the Prussian Academy of Sciences and Humanities, the state of knowledge about Einstein’s resignation from the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities, with its thematic and chronological links to the developments in Berlin, seemed entirely hopeless. The events were shrouded in obscurity. The problem was not that resigning from the Bavarian Academy had been an event of no great significance in Einstein’s life: Afterall, he had only been a corresponding member of the academy in Munich since 1927 and his affliation with it had been fairly loose, whereas the Prussian Academy had granted him a regular full-time salary since 1914 and exempted him from obligations outside of research. The obscurity was rather a product of the desolate state of the sources. Only the two documents Einstein himself published in 1934 were known. One of these was a letter dated April 8, 1933, from the presiding committee of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities, in which Einstein was asked “how you understand your relationship with our academy after what has taken place between yourself and the Prussian Academy,” and the other was his reply, dated April 21, 1933, requesting that his name be “removed from the list of members.”12

No further information was available, for the academy’s building in downtown Munich was destroyed during the Second World War. Furthermore, it seems highly likely that records were also intentionally purged at some unidentifiable point, because the volumes missing from the rescued proceedings of the mathematics and natural sciences section at the academy and its presiding committee would cover exactly the span of time that is relevant here. At any rate, the academy no longer has any records of its own on the case.

In the absence of substantiated information, an oral tradition outlining these events was able to thrive. It suggested that Leopold Wenger, the academy’s president in 1933, had acted unilaterally “without the knowledge of members of the academy.” This account, which can still be found in recent publications,13 was first committed to writing by Walther Meißner for the academy’s bicentennial celebrations in 1959,14 although Meißner himself had only been elected to the academy in 1938. As Wenger had left Munich as early as 1935 and died in 1953, he was unable to pass comment on Meißner’s version.

Most recently, however, new source material has fortunately come to light that makes it possible to subject the traditional account to historical scrutiny for the first time. At the same time, these sources shed a little light on attitudes within the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities toward the Nazi ascent to power, an issue that has proven somewhat elusive up to now. The freshly discovered material also reveals a second major case of antisemitic discrimination at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences that had previously been entirely overlooked: the ousting of Richard Willstätter, winner of a Nobel Prize in Chemistry, from the academy’s presiding committee in early May 1933.

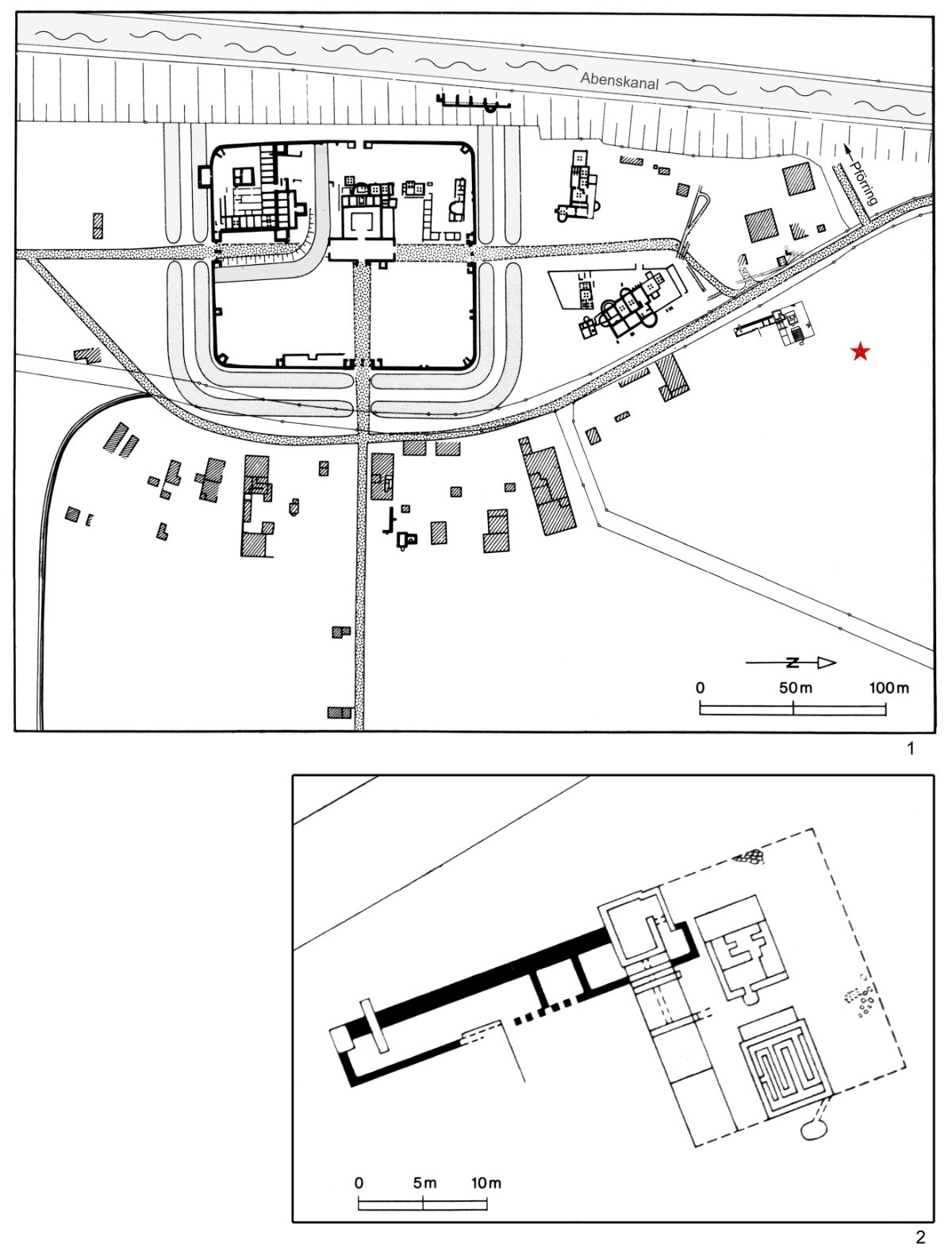

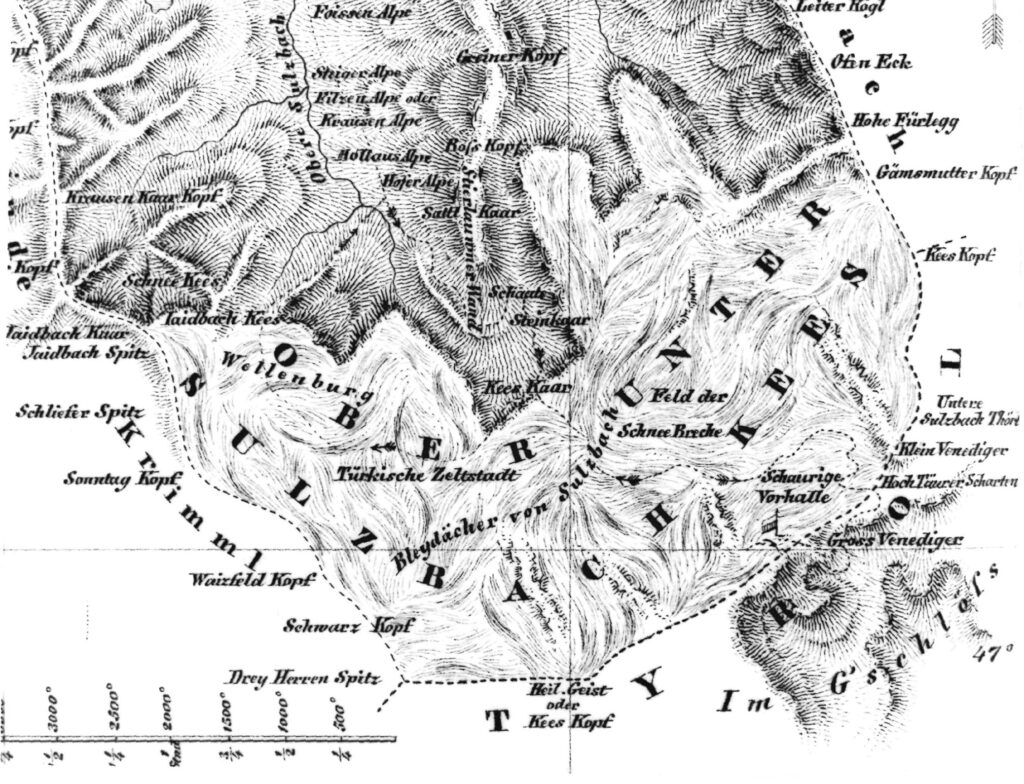

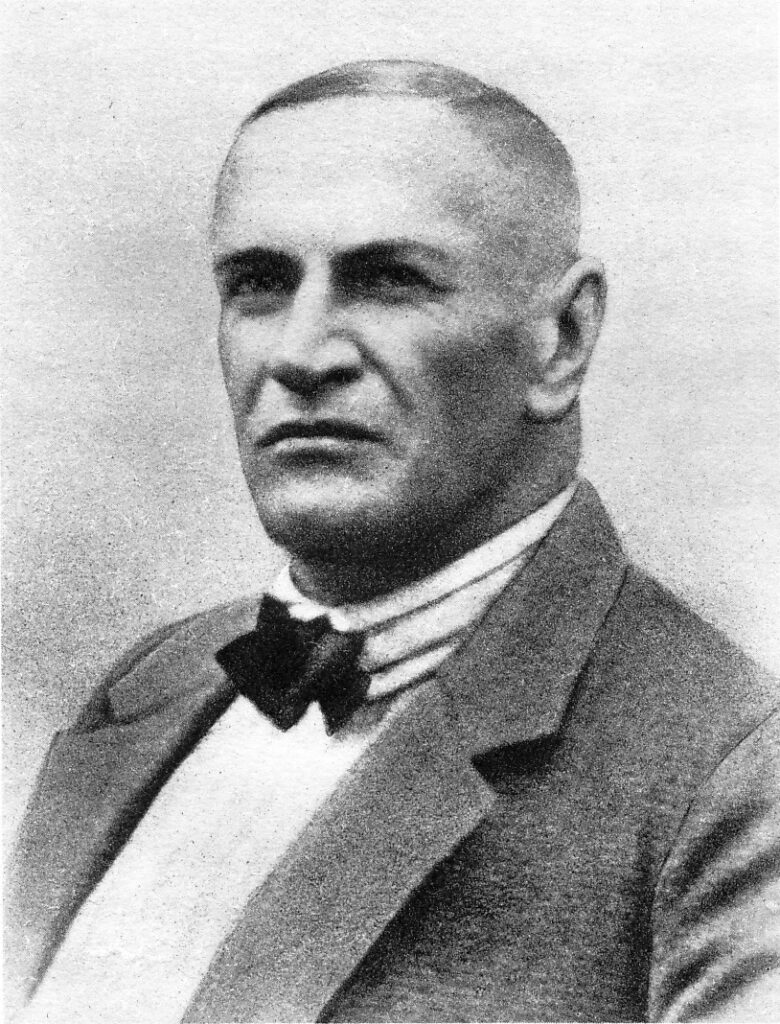

Several documents with academy provenance that relate to the above-mentioned events have survived despite the near total loss of records. They are found in the personal literary estate of Georg Leidinger (1870–1945), who was a member of the academy’s presiding committee in 1933. His primary role was at the Bavarian State Library, where he headed the manuscripts section. He had been an extraordinary member of the Bavarian Academy since 1909 and a full member since 1916. He was elected secretary of the section for history on December 3, 1932, and took part in every meeting of the academy’s presiding committee until 1941 in this capacity. After his retirement in 1936, he lived in Marquartstein in the mountains of Upper Bavaria, where he died shortly before the end of the war.15

Leidinger had deposited some of the files and correspondence that he had accumulated in various academic roles in the Bavarian State Library, where they escaped destruction during the war because they had been removed for external storage. The larger portion of his files, which he had kept in his country house, were handed over to the State Library by his widow in 1946. Leidinger’s former colleague and intimate, Albert Hartmann—who, together with two librarian colleagues, had once been “the spearhead of National Socialism in the Bavarian State Library”16—merged the two parts of the estate to form the “Leidingeriana” collection as had been agreed upon with Leidinger many years previously.17

A handful of pages within this very extensive estate deal with Einstein’s exit from the academy. For reasons hardly attributable to coincidence, they were filed in a location (cataloged under “Monumenta Boica”) that made them unlikely to be discovered.18 Nobody ever looked for them there, nestled among documents about an obsolete series of primary sources (discontinued in 1956) for which Leidinger was responsible as the chairperson of the Commission for Bavarian Regional History at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities. But three of the five folders labeled as “Monumenta Boica” actually contain documents on other academy matters in which Leidinger was involved. Folder 2 contains Leidinger’s papers on the “Einstein case,” which he describes as such on the first sheet.

Nor does the wealth of source material supplied by Leidinger end there. As a civil servant accustomed to documenting his actions in detail, he also kept a diary in which he conscientiously recorded day-to-day events from 1906 until his death. As Leidinger expressly bequeathed this diary to Albert Hartmann personally,19 it only reached the Bavarian State Library after Hartmann’s death in 1973, when it was placed with the rest of his estate.20 “Acta bibliothecaria,”21 the curious label adopted by the author, was undoubtedly a factor that contributed to historians overlooking this rich source for a long time; it was only evaluated selectively for the appraisal of questions relating to library history.22

Naturally enough, the diary mainly reports on developments in the library, Leidinger’s main sphere of activity. In addition, however, Leidinger served on a broad range of academic committees, and he made little distinction between official and non-official matters in his diary. His notes cover all the letters he wrote or received; discussions, meetings, conferences, and exhibitions in which he was involved; and purely personal matters—conversations in corridors or trams, interesting encounters in the city, vacation experiences, and a wealth of other details. They provide a remarkably detailed description of the daily life of a man who played a central role in Munich’s cultural and academic life.

Hartmann, who claimed to have been aware of the existence of the diary volumes since 1936, described the purpose of these notes as he prepared to bequeath them to the library. He noted that Leidinger kept these notes “mainly for himself, as an aid to memory, but also to record certain events, circumstances, and relationships for posterity.”23 Both of these aspects are indeed important and need to be considered when evaluating the material. Keeping track of his extensive and varied correspondence and meetings was certainly a key motive for Leidinger. The “Acta” are a dull, dry read with their notes in a staccato telegram style detailing who had written to Leidinger when and about what, how and when he had replied, what offprints he had received, and which ones he had dispatched to specific recipients.

Interspersed between these terse notes, however, Leidinger sometimes commented with great clarity and feeling on the matters reported. His intention of leaving a record for posterity shines through quite clearly in these passages. Leidinger, who was always of a very confident bearing—at least outwardly—saw his views and judgments as important enough to be communicated to future generations. He deliberately stylized his notes with this purpose in mind. Readers should not be deceived: As the steady handwriting and the occasional use of very slight flashbacks and foreshadowing show, the diary notes are not a direct and immediate record of events. Leidinger probably made notes in an appointment calendar and wrote them up as diary entries a little later. This explains why especially striking events, such as the Hitler putsch or the Nazi Party’s seizure of power, are described in dramatic terms, presumably to demonstrate—and not without pride—the author’s proximity to them.

I

Albert Einstein’s resignation from the Prussian Academy of Sciences and Humanities was a direct consequence of the Nazi takeover of power in Germany. Einstein was a visiting researcher at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena at the beginning of this episode, and he had already resolved to relocate his professional life to the United States. By the time of the Reichstag fire (in the night of February 27/28, 1933), it had also become clear to him that he had no intention of setting foot on German soil again in the near future. He announced this decision in a public statement on March 10 in which he explained that political freedom, tolerance, and the equality of all citizens before the law did not currently exist in Germany, where people who had contributed substantially to the prospering of international relations were threatened with persecution.24 On March 18, the Prussian Academy of Sciences asked Einstein to inform them “of what had actually happened” as newspaper reports indicated that he had “made public statements opposing the current government in Germany.”25

This letter cannot have reached Einstein. Unaware of its existence, he wrote a letter to the Prussian Academy on March 28, during his passage back to Europe by ship, that only briefly alluded to the “current state of affairs in Germany” to explain that “dependence upon the Prussian government” had become “intolerable” for him and that he would thus “resign from my position at the Prussian Academy of Sciences and Humanities.” The academy received this letter on March 30.26 Einstein had left the academy only a few days before he would have been expelled from it. On April 1, 1933, the day of the nationwide boycott of Jewish businesses, doctors, and lawyers, the academy published a press release in which it expressed “outrage” at Albert Einstein’s “participation in atrocity agitation in America and France” and emphasized its support for the “national idea,” a position from which it saw itself as having “no cause to regret Einstein’s resignation.”27 This press release was picked up by all the major German daily newspapers.28

At this point in time, the National Socialists were going to great lengths to inflame public sentiments in Germany.29 They told the German public that international press reports detailing the mistreatment of Jewish citizens public since the Reichstag fire were “atrocity agitation” and obviously the result of Jewish manipulation of the press. Julius Streicher founded a “Central Committee to Repulse Jewish Atrocity and Boycott Agitation.” As its leader, he spoke in Munich’s Königsplatz Square on March 31 to an audience of (according to a report in the Völkischer Beobachter) an estimated one hundred thousand people who had gathered to demonstrate “against the Jewish atrocity agitation.”30 Two days later, the paper proudly announced that Nazis had attacked Jewish judges and public prosecutors in Munich and that the courthouse known as the Justizpalast (Palace of Justice) had been “swept clear” of Jews.31

These developments can hardly have failed to impress themselves on the consciousness of those in charge of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities. The Justizpalast was only a short walk away from the academy building in Neuhauser Straße. Leopold Wenger, a scholar of ancient law, had only been elected to the presidency of the academy on November 12, just a few months earlier.32 In accordance with the academy’s statutes, he had advisers in the form of his predecessor, the classical philologist Eduard Schwartz,33 and four section secretaries, two from the academy’s historical-philosophical section and two from its mathematical-scientific section. The archaeologist Paul Wolters34 and the mathematician Walther von Dyck had extensive experience with academy business,35 while Georg Leidinger was, as mentioned above, a relative newcomer. The presiding committee also had a Jewish member, Richard Willstätter,36 a Nobel laureate in chemistry who had joined the committee in 1930.

The controversy over alleged atrocity propaganda took place a mere three weeks after a Nazi regime had been installed in Bavaria.37 How political events would continue to unfold was not remotely foreseeable at this point. The presiding committee at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities could not yet have developed a firm stance of its own. It therefore resorted to “lying low” and keeping quiet as long as no actions were directly demanded of it, with the calm self-confidence of an institution that had existed since 1759. The principle of Quieta non movere [Do not move settled things] was the order of the day,38 and it worked for a few years—the new regime did not initially meddle in the academy’s affairs.39

But in the “Einstein case,” a policy of non movere was seemingly deemed infeasible after the events at the Prussian Academy had become publicly known. On April 4, 1933, the day after the Jews had been “swept” from Munich’s Justizpalast, President Leopold Wenger wrote to the Prussian Academy of Sciences and Humanities to request that he be provided with a copy of the current correspondence with Einstein and with Einstein’s current postal address and saying that “the greatest possible expediting” was indicated “given the urgency of the matter.”40 The documents were accordingly dispatched to Munich by airmail on April 5.41 Leidinger’s diary notes on the “Einstein case” begin three days later, on April 7: “Committee meeting at the academy: Einstein case. The Berlin documents have arrived. No result yet after two hours of discussion. The committee members should each try to draft a letter to Einstein by tomorrow.”42

These few sentences alone suffice to demonstrate that Wenger was not acting unilaterally but had raised the matter in the presiding committee of the academy. It is also clear that the presiding committee struggled with its deliberations. The fact that one of its members, Willstätter, was himself Jewish had to be considered. In addition, the composition of the presiding committee was diverse not only in terms of the disciplines represented but also in its age range. Wenger, Leidinger, and Willstätter were all aged around sixty. Schwartz, Wolters, and von Dyck were already in their midseventies. Presumably with these latter three members in mind, Leidinger had noted “Business transacted with an awful impression of the worst kind of senility” in his diary regarding his very first meeting as a member of the presiding committee on December 21, 1932.43

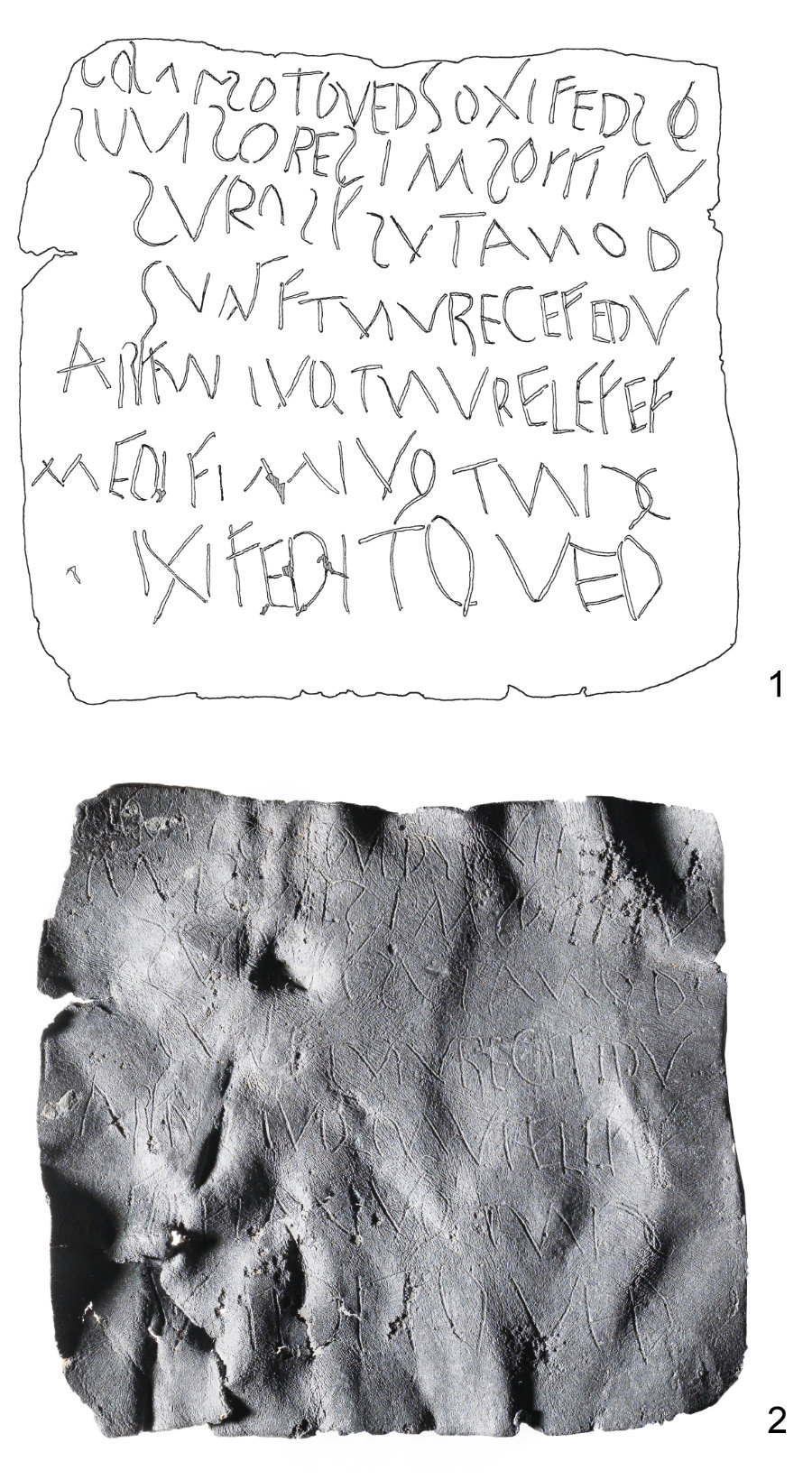

Leidinger’s diary skips the following two days, a rare occurrence, and says nothing about the fresh meeting of the presiding committee scheduled for April 8. But—as noted at the beginning of this article—his literary estate also contains several pages of notes relating to the “Einstein case.” On their cover page, he wrote: “A discussion of this is presumably unnecessary.” The first page bears a pencil draft in Leidinger’s hand, dated April 8, for the letter to be addressed to Einstein.44 It is not clear whether these are Leidinger’s notes taken during the meeting or a draft he had formulated before the meeting. As the text contains only a few deletions and rewordings, it seems likely that Leidinger brought a finished draft to the meeting, as had been agreed the previous day; multiple people struggling to formulate a draft together would have presumably engaged in more intensive rewording. Be that as it may, the text as recorded here is identical with the text of the letter that was sent to Einstein.45

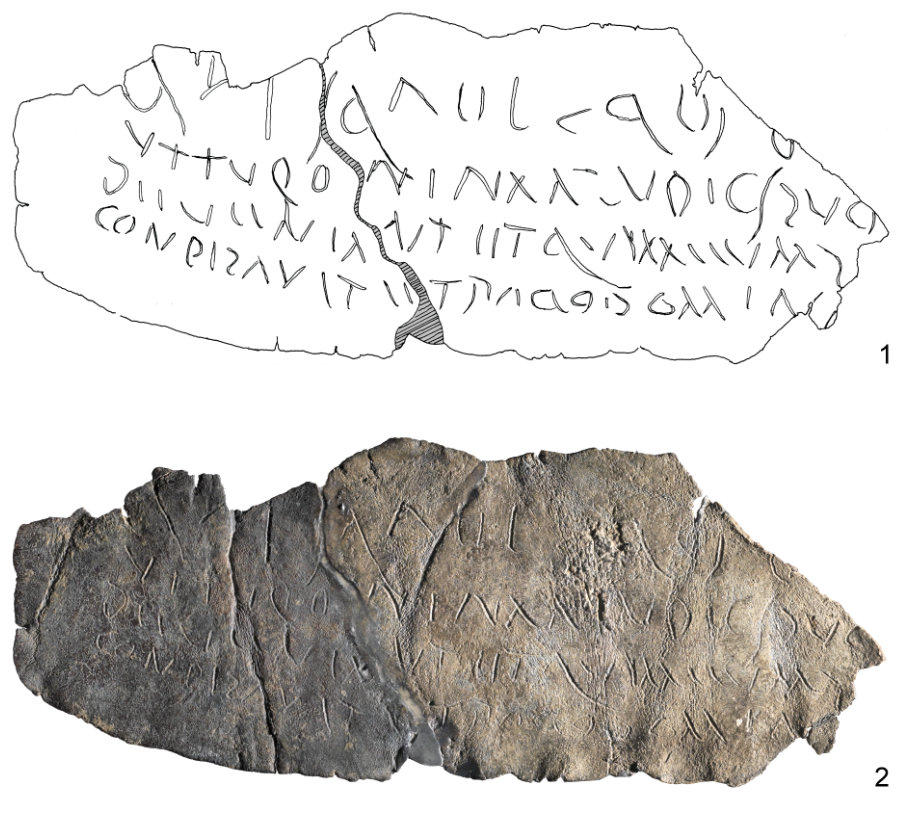

A second page in the file bears the heading: “Resolution of the Committee of the B. Academy of Sciences and Humanities 8. IV. 33.” Containing just one succinct sentence and penned by an as yet unidentified hand, this memorandum urges the mathematics and natural sciences section at the Bavarian Academy to consider “whether it does not wish to apply for Einstein’s exclusion with regard to Section 11, Subsection 3 of the statutes of the academy.”46 It is easy to see that this is the key document in the entire case, for it reveals that the presiding committee had no intention of waiting for Einstein’s reply but was determined to pursue his expulsion even before its own letter to him had been drawn up. This cited passage from the Ordinance on the Organization of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities in the version of July 18, 1923, states: “The Academy may decide to expel a member at the request of a department with a three-fourths majority of the full members.”47

Leidinger did not document which presiding committee members were present at the meeting on April 8, but it seems highly likely that the committee was complete. Leidinger was generally thorough in such matters and would presumably have made a note of any absences.48 The letter that the academy sent to Einstein on April 8—which became public only because Einstein published it—was signed collectively by “The Presiding Committee of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities.”49 It was decidedly brief, containing just one sentence of true significance: “We must therefore ask you how you understand your relationship with our academy after what has taken place between yourself and the Prussian Academy.”

There was no reply from Einstein for quite some time. This was in part perhaps because the Prussian Academy of Sciences and Humanities had forwarded an address (“c/o Prof. P. Ehrenfest, Leiden, Witte Rosenstraat”) to its counterpart in Munich that proved to be inaccurate.50 On April 18, the syndic of the Bavarian Academy, Eugen von Frauenholz51 inquired again in Berlin about the progress of correspondence with Einstein and asked for copies.52 On April 22, the section for mathematics and natural sciences, which was responsible for the case according to the academy’s statutes, dealt with it without knowing Einstein’s stance on the letter the presiding committee had sent to him. As the minutes of the section for this period have been lost, Leidinger’s diary provides the only known documentation of this meeting. On April 24, a Monday, Leidinger noted: “Telephone call to the academy to ascertain the result of the meeting of the natural sciences section on Saturday. Huwig53 says: it should first be asked whether the letter has reached Einstein’s hands. Oh, these Schwachmatici [feeble people]!”54

The members of the section or department, which naturally also included Willstätter—who, as a member of the presiding committee, may even have chaired this meeting—clearly could not bring themselves to move for Einstein’s expulsion, at least not yet.

Einstein, on the other hand, had already decided to resign from the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities. He had remained in Belgium after disembarking in Antwerp and taken up residence in the seaside resort of Le Coq-sur-Mer near Ostend.55 In a letter dated April 21, 1933, he expressed his “wish to have my name removed from the members’ list” and explained this step with clear criticism of the stances taken by “German learned societies.”56

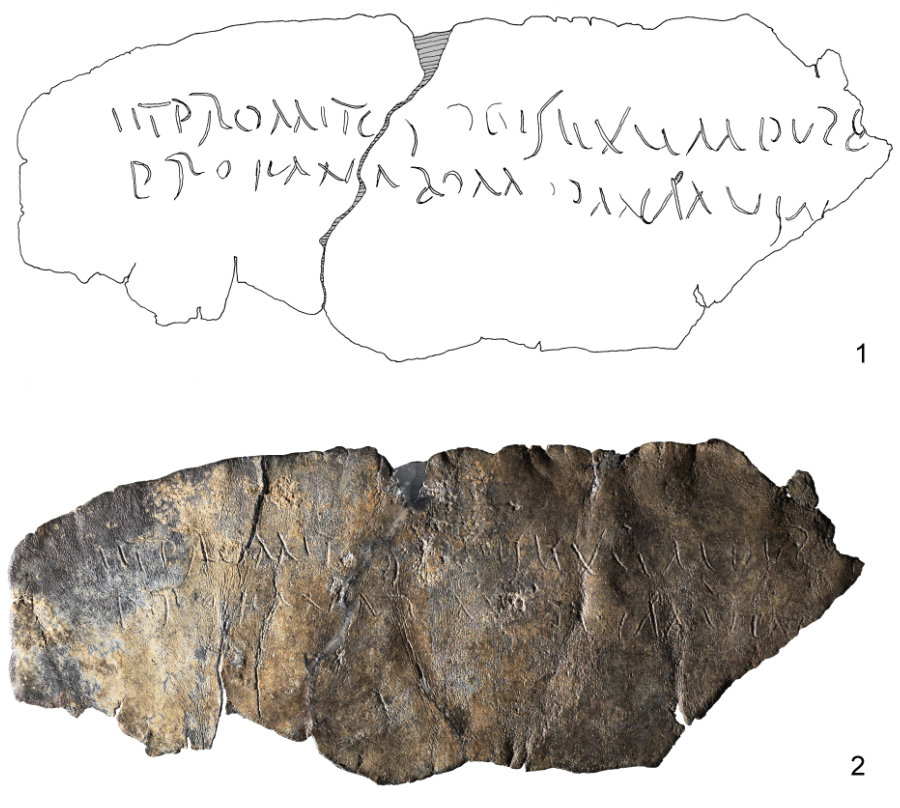

This letter must have reached the academy after April 24, 1933. Leopold Wenger, its president, had not awaited the outcome of the matter and had used the days toward the end of the semester break for a brief vacation. It was thus Wenger’s deputy, Eduard Schwartz who informed the section secretaries in writing on April 27 that “Professor Dr. Einstein has declared his resignation from the number of our academy’s corresponding members.”57 According to the entries of Leidinger’s diary, the presiding committee discussed the “Einstein case” one final time at its meeting at 11 a.m. on May 3 to determine whether to respond to Einstein’s resignation. They decided to issue “only a short note acknowledging receipt.”58

A handwritten page in Leidinger’s estate bearing this date contains a note in his hand that Schwartz had chaired the meeting in his role as deputy. This is followed by the information that it had at least “been decided to write: the acad. has taken note of your letter of resignation.”59 At the meeting of the philosophical–historical section on May 6, 1933, mention was made in passing of Einstein’s “resignation without [further] discussion.”60

II

Leidinger’s notes on the “Einstein case” end there. For all their laconic brevity, they represent a meaningful source of information about how the academy treated its prominent member. But they also shed light on their author, naturally enough, and illuminate his role as a significant representative of the academy and a person active on many of its commissions. Leidinger’s personal attitude regarding the events was conveyed in just a few scant words that were in keeping with his general diary style: “O diese Schwachmatici!”—“Oh, these feeble people!”

Expressions from student slang like Schwachmatikus belonged to his standard repertoire. Leidinger maintained close ties to his Munich student fraternity, the influential Akademischer Gesangverein, as one of its “old men.” He had even become its historiographer, although he generally preferred compiling editions and shied away from producing major historical accounts.61 Among the librarians at the Bavarian State Library, this choral society—generally referred to simply as der Verein, “the association”—enjoyed a dominant and unchallenged position. Fraternity lingo was cultivated in everyday life in these circles. People did not confront each other, for instance, but engaged in coramage (a fraternity term for a formal interrogation carried out by a man who felt his honor had been offended, or his chosen representative, of a person deemed to have caused offense).62

A Schwachmatikus was simply a weakling or a feeble person.63 Leidinger regarded the academy members who could not bring themselves to petition for Einstein’s expulsion as such weaklings. Turning this around, the inconspicuous diary note underscores that Leidinger was an adament advocate for Einstein’s removal from the academy—and regarded any discussion of the matter as superfluous and unnecessary.64

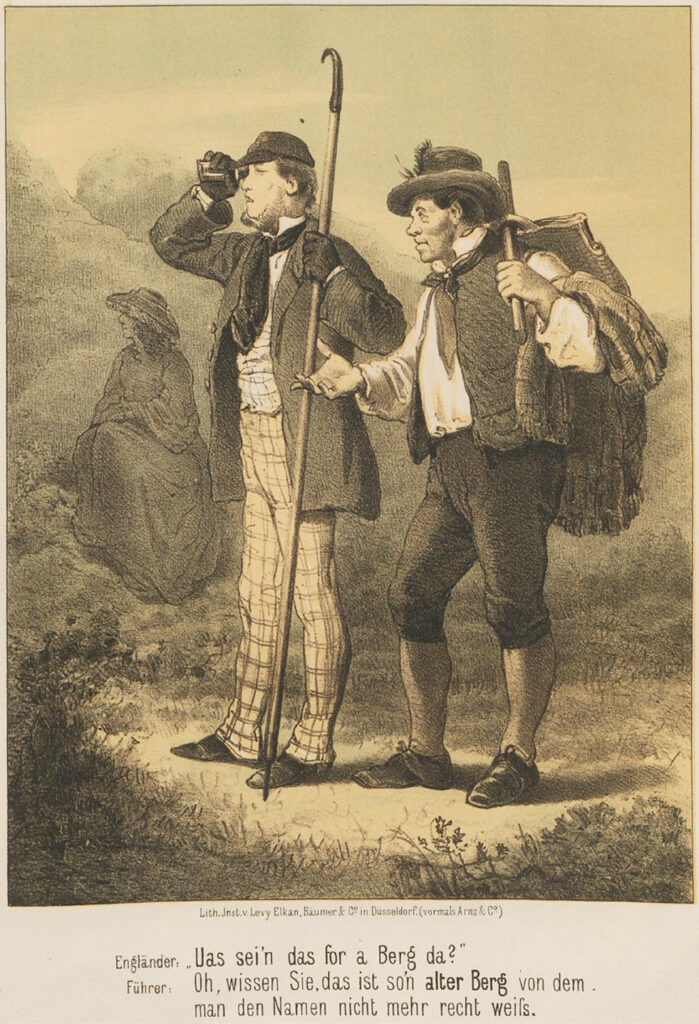

This raises the question of what motivated his stance. Leidinger’s and Einstein’s fields of disciplinary expertise were in no way adjacent, and Leidinger was certainly not personally acquainted with Einstein—he could not have known more about him than what could be gleaned from newspapers. As a regular reader of the Münchner Neueste Nachrichten and the Völkischer Beobachter, Leidinger would not have read anything about Einstein during the days that are relevant here, but he would have seen many general allegations about the alleged Jewish world conspiracy. That said, some broader consideration of his political views is necessary here.

Leidinger, a Protestant Franconian of lower middle-class origins, was strictly deutschnational—an adherent of a conservative and Protestant brand of German nationalism—before 1933. He was resolutely opposed to the political Catholicism that dominated Bavaria and convinced that it was to blame for the fact that he was never appointed to the role he believed himself destined for, the general directorship of the Bavarian State Library. This explains the satisfaction he derived from the changeover of power in Munich and Bavaria on March 9, 1933. He recorded the prevailing mood as general jubilation and “strong hope” (which may have been predominantly his own).65 He would have liked to see the “seizure of power” taken even further; Franz von Epp’s appointment as Reichs-Polizeikommissar (Reich Police Commissioner), which he read about in the newspaper the next day,66 was, in his words, only a “half-measure! What a shame that they didn’t get a firm grip on things right away, as will hopefully still happen.”67 Whether Leidinger only wanted to see the back of the conservative Catholic government or whether he wanted to see democracy liquidated altogether need not concern us here. At any rate, he was highly satisfied with these unfolding political developments.

Leidinger held national honor, or what he understood as such, in high esteem, and sins against it were unpardonable. He regarded Ludwig Quidde, a fellow academy member and colleague, as an elendiger Volksverräter—a “wretched traitor of the people”—because Quidde was a pacifist.68 Einstein, however, was not merely a pacifist but had even publicly distanced himself from Germany and thus, in the Nazi interpretation, likewise become a traitor of the people. That alone would presumably have been enough to turn Leidinger against him.

Furthermore, Einstein was Jewish. Leidinger’s publications are not known to contain antisemitic statements, but his aversion to Jewishness in general and to certain Jews in particular shines through all the more extensively in his diaries. Antisemitic rhetoric features pervasively in his notes from 1918 onwards. This point in time is not coincidental; like so many of his contemporaries, Leidinger blamed Jews for the Bavarian Revolution of 1918/19 and the events that occurred in its aftermath.69 Beginning with the crises of the early 1930s, antisemitic comments in his diary become increasingly frequent. After the Nazi seizure of power, Leidinger shed all inhibitions about displaying this aversion openly.

The fact that Jewish citizens were physically attacked and faced mortal threats in March 1933 did not bother him in the slightest, not even when he was personally acquainted with the victims. Leidinger had previously willingly engaged the legal services70 of the Munich lawyer Dr. Joseph Weil (1886–1940),71 who was in turn an avid user of the Bavarian State Library.72 When Leidinger had a consultation with Weil on March 14, Weil told him that he had been abused by Nazi thugs on the night of March 10–11. At that point, Leidinger refrained from passing any comment on this in his diary.73 But when he saw Weil again two weeks later—by which time Weil’s mental distress had probably become severe—he could only think of one word for him: “disgusting.”74

Dr. Michael Strich (1881–1941),75 a private scholar of Jewish origin in Munich, was not physically attacked at this point. He had known Leidinger since the First World War, in which he had fought for Germany on the western front.76 Strich offered the Commission for Bavarian Regional History an extensive book manuscript in 1928 that entered a production process supervised by Leidinger in 1930.77 This required numerous personal meetings, and Leidinger rarely neglected to put his personal dislike of Strich into words when documenting these conversations. September 5, 1930: “The Jew Strich … stinks terribly of sweat and tobacco”;78 July 25, 1932: “this impertinent Jew”; August 18, 1932: “the insolent Jew, Strich”79 etc. From the spring of 1933, Leidinger no longer made himself available to Strich as a contact person, although numerous details about the delivery of the book remained to be discussed.80 He evaded all attempts at contact for months and put Strich’s letters aside as “whining.”81

To fully grasp the import of Leidinger’s behavior toward both of these men, it must be borne in mind that both of them were completely “assimilated.” Weil had a Catholic father. Strich was a keen researcher into seventeenth-century Bavarian history and accepted Catholic baptism in 1935. Leidinger’s antisemitism was therefore obviously grounded in racism.

In other words, the head of one of the most outstanding cultural collections in the world, the manuscript section of the Bavarian State Library—a man who interacted with scholars from all over the world in that context—put up no resistance whatsoever to adopting vulgar antisemitic tropes. While the biographical context to this cannot be explored here, it bears noting that Leidinger harbored a great many other grudges against collectives and individuals in addition to his antisemitism: These included women in academic professions (“geese”82), Catholics (“dishonest”83), the ministerial bureaucracy (“idiots”84), his own superiors (“useless!”85), and even the Bavarian Minister of Education (a “country bumpkin”86)—the self-confidence of the brushmaker’s son who had reached the highest echelons of academia must have been threatened from all quarters. It bears recalling once again that that this rhetorical belligerence did not arise situationally during temporary losses of composure, but was well considered by Leidinger: These were formulations that he did not wish to see committed to fire after his death but, on the contrary, preserved for posterity.

The source situation does not allow the attitudes of the remaining members of the presiding committee to be discerned with the same clarity. President Wenger notably chose to avoid having his name directly attached to the academy’s decision. The letter to Einstein was signed by “the Presidium” although the statutes of the academy made it plain that the president was responsible for conducting its correspondence as part of his duties.87 When Einstein’s reply arrived, Wenger was not in Munich and had left the task of dealing with the matter to his deputy, Schwartz.

Some parallels in habitus between the two privy councillors Schwartz and Leidinger probably existed. Schwartz also thought along deutschnational national-conservative lines88 and had welcomed the Nazi seizure of power, but he was not an avowed supporter of the regime. From the Nazi point of view, however, he was simply too old and too conservative and rapidly found himself relegated to the margins of academia.89 Schwartz was also, rumor had it, “no friend of the Jews.”90 Leidinger reports that his re-election as president of the academy was prevented by the mathematics and natural sciences section in 1930, “fiendishlyly, due to Jewish intervention!”91 Schwartz’s son reports that a certain emotional block around this issue existed in the family. He says that his father considered “the Jewish, invariably left-wing influence on the press and parties” disastrous and “counseled restraint in matters connected to [academic] appointments.”92

The roles of Wolters and von Dyck are not visible at all in the few surviving documents. Whether Wolters could have exerted any great influence on the course of developments seems decidedly doubtful. He had probably become prematurely senile. Leidinger considered Wolters no longer capable of conducting academy business and repeatedly attested “senility of the worst kind” to him in his diary.93 Although the known sources shed no light on Willstätter’s position, antisemitism can definitely be ruled out in his case.

That still leaves the role of Walther von Dyck to consider. Although von Dyck expressed a fundamental lack of understanding for the tumultuous course of the “national revolution,”94 his letters contain very clear negative statements about the “Jewish question.” He proclaimed himself “no admirer of the Semites” as early as 1894.95 In 1921, he attributed “the ruin … of our German being” to “appalling cronyism in Berlin”—behind which he suspected Jewish intrigues.96 Von Dyck’s personal dislike of Fritz Haber, a colleague in the Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft who was that association’s vice president and a “non-Aryan,” was well known. When Haber resigned97, von Dyck remarked expressly in a latter dated May 14, 1933, “that I never considered the election …, especially of Haber, to be good.”98

The state of hearts and minds among the presiding committee’s membership is clear enough from this overview to allow the conclusion to be drawn that it was unlikely, in this context, that the “Einstein case” could have taken a different turn. On any committee, a tiny handful of people who were “zealotss, possessed, or obsessed” sufficed to make “any opposition impossible.”99 Those who were not among their number might try to tell themselves that it was “more sensible” to sacrifice an individual member than to expose the entire academy to political attacks. The exact distribution of responsibility is probably beyond clarification at this stage. Eduard Schwartz was ultimately the person who formally acknowledged Einstein’s departure. It is one of the ironies of history that he, of all people, is himself now counted among the scholars “driven out” by the Nazi regime because he was frozen out of the academy—likely mainly for age-related reasons.100

III

Apart from the Einstein case, the page that Leidinger prepared for the meeting of the presiding committee on May 3 also contains two further lines of text that may initially seem puzzling. One reads “Angelegenheit der Betriebszelle” [the active cell affair] and the other contains only the name “Willstätter.” This cryptic note can be decoded by drawing on Leidinger’s diary entries. Among other notes committed to his diary on May 3, he remarks: “The active cell at the academy: The busybody v. Frauenholz paid a visit to Willstätter and tried to persuade him to resign as section secretary. How outrageous! It is not clear to me whether Schwartz was behind this as well. The president, who has just returned from vacation, knew nothing about it, and now he has to smooth out the matter and explain that it was based on a mistake.”101

The events described here had previously been completely hidden from historical research. No one had even registered that Willstätter’s name had simply disappeared from the list of secretaries in the yearbook issued by the academy in 1933.102 This is odd for reasons of timing alone, since the terms of office of section secretaries lasted for two years and it is known that Willstätter became a section secretary in 1930.103 Heinrich Wieland’s belated obituary of Willstätter, who died in 1942, had, moreover, made an admittedly oblique reference to Willstätter already having had “to bid farewell to our body eight years before his death [i.e., in 1933] as a victim of political vandals.”104

Willstätter was one of the academy’s most prominent members. In 1915, he had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his groundbreaking research into the chemical structure of chlorophyll, among other topics. That same year, he was appointed to a professorship at the University of Munich, and his corresponding membership (1914) in the academy was subsequently upgraded to a full membership (1916). In 1930, the natural sciences section elected him as their secretary, which made him a member of the presiding committee—together with the remaining section secretaries, the president, and the previous president.

The attack on Willstätter that Leidinger reports is confirmed and commented on in detail in another hitherto unnoticed document relating to academy history, the memoirs of the “busybody” Eugen von Frauenholz, who was the academy’s syndic at the time. Frauenholz had been a career officer in the Bavarian army until 1918. He had then undertaken university studies, obtained a doctorate and later a habilitation degree, and established himself as a military historian. From 1928 onwards, he acted as the academy’s syndic, which essentially meant that he was its managing director—the role did not necessarily demand extensive legal knowledge. He was ousted together with President Karl Alexander von Müller105 in 1944 and took early retirement.106

During the collapse of the Third Reich in 1945, Frauenholz wrote his memoirs for later publication. They are dated from April 17 to July 20 and have remained unprinted and largely unread among the papers of his literary estate to this day.107 In lengthy passages on the “Jewish question,” Frauenholz emphasized his lack of understanding for the actions taken against the Jewish population; he claimed to have made no effort to hide, as syndic, “my understanding that every Jew should be treated as he deserves, and that Jews who were important scholars could not be excluded.” He personally had “not had any bad experiences with Jews.”108 He then begins to describe the “Willstätter case”:

Now, I did have one experience that went in the other direction. Privy Councillor Willstätter, the well-known physicist, was a Jew and a department secretary at the academy. When a directive came out forbidding the appointment of Jews to offices, I considered it my duty as syndic to go to Privy Councillor Willstätter, without saying anything to anyone, and to bring this decree to his attention in a private conversation, so that he could resign from his office himself if he wished to do so. I expressly told him that I was coming without having informed the president in advance; after Goebel’s death, the acting president at the time was once again Privy Councillor Schwartz, who was no friend of the Jews. I told Willstätter that I wanted to bring the directive to his attention in confidence so that he could decide for himself whether he wanted to leave office voluntarily or to await further developments. What he wanted to do was for him to decide; I just wanted to spare him and the academy from unpleasantness, and nobody at the academy knew I had visited him. His behavior was not quite correct, because he raised the matter at the next meeting of the presiding committee, not only referring to me—which I had never forbidden him—but also stating his conviction that Privy Councillor Schwartz was behind my visit. I had given him assurances to the contrary.109

Frauenholz wrote his account in Matrei in East Tyrol from memory, without access to documents, and some details are blurred or inaccurate. Willstätter was not a physicist, of course, and Karl von Goebel, who had died after a short period in office, had not been succeeded as president by Eduard Schwartz but by Leopold Wenger, whose tenure in the role also only lasted for a few years. But this text by Frauenholz, an independent second witness, fully supports Leidinger’s account. Its emergence in the face of the German defeat naturally implies that readers must exercise caution; self-apologetic tendencies should be expected. But the credibility of this passage is supported by the fact that Frauenholz had no incentive to protect Schwartz, who had already died, and to whom he could easily have shifted responsibility here.

Perhaps the honorable intentions Frauenholz claimed can even be credited to him, a man who cultivated chivalrous and courtly ideals and who had ridden into battle as an old-school heavy cavalryman with a lance and a saber. He was close to the former Bavarian royal family and a convert to Catholicism, and he had served as a chamberlain to Prince Ludwig Ferdinand since 1923. He clearly had no ideological affinity with National Socialism; at the University of Munich, where he lectured on military history, he was considered incapable of “representing the military sciences in the spirit of National Socialism.”110 He did not join the Nazi Party until 1941.111

The “directive” that Frauenholz was reacting to was presumably the “Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service” passed on April 7, 1933. Its aim was to remove all “non-Aryans” from public service positions, and a rapid series of increasingly draconian regulations followed that targeted Jews for discrimination in every area of public life. The academy soon began dismissing Jewish members of its project staff.112 A third such decree, issued on May 6, 1933, expressly mandated the dismissal of university professors and honorary public servants who had already been discharged from their duties.113

Remarkably enough, there seems to have been little official pressure exerted on Jewish instructors at the University of Munich at this point in time; only Hans Nawiasky—who had long been a persona non grata on account of his politics and his alleged relativization of the “shameful peace” of Versailles—had already been suspended from his teaching duties on April 20.114 Frauenholz was thus getting ahead of events to some extent with his intervention in the academy. To deduce just how far ahead he was, however, one would need to know when exactly he visited Willstätter, which is unclear. All that is definitively known is that Willstätter sent a letter to Friedrich Schmitt-Ott, the president of the Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft, on April 25 to tender his resignation from his position on the expert committee for chemistry on the grounds that his recent election “did not yet take changed circumstances and opinions into account.”115 It is possible that Willstätter became aware of this sea change via Einstein’s letter of resignation if it arrived in Munich on that day. Alternatively, Frauenholz’s visit could also explain this step on his part. In this latter case, Frauenholz would have launched his plan to “Aryanize” the academy’s presiding committee before the Bavarian state parliament passed its own Enabling Act—in its final session in the Third Reich, on April 28/29, 1933—that made it clear that the “national revolution” had also prevailed in Bavaria.116

Whatever the exact sequence of events, it had become foreseeable by this point that “non-Aryans” would not be able to retain prominent positions in public life. The problem that Frauenholz probably foresaw for the academy was that its statutes did not supply any mechanism for excluding a member of its presiding committee. The only options for removing Willstätter from the committee were to expel him from the academy entirely, which had proven somewhat difficult even in Einstein’s case, or to nudge him into leaving voluntarily. Academic etiquette, which was maintained even during the drastic purges of 1938, demanded asking colleagues to resign from their offices rather than dismissing them outright.

As we have seen, Leidinger had no empathy at all with oppressed Jewish fellow citizens and colleagues, and his perception of this incident as “outrageous” was clearly not because of its antisemitic tendencies. He generally disliked the “noble Mr. v. Frauenholz”117 and regarded his move as a form of interference with the rights of academy members. This explains why he referred to him in his notes as a Betriebszelle—a word that should not be understood in its Nazi meaning (Betriebszellen-Organization as a workers’ organization) but as an allusion to Betriebsamkeit (busy activity).

Willstätter could have been protected by his unimpeachable patriotism: He was a signatory of the infamous “Manifesto of the Ninety-Three” in 1914, a document that sought to justify German military operations in Belgium during the First World War, and he had not distanced himself from it later, as some other signatories had.118 He had been awarded the Iron Cross in 1917 for his scientific research on poison gas defense. This distinguished him sharply from Einstein, an avowed pacifist. In addition, Willstätter was—also in contrast to Einstein—highly decorated in Bavaria; in 1925, he had (together with Eduard Schwartz!) been among the first four researchers admitted to the noble Maximilian Order for Science and Art after the end of the monarchy.119

Nevertheless, Willstätter does not appear to have received any backing from the presiding committee at its meeting on May 3, 1933. This is the conclusion that must be drawn from his reaction to the meeting, which Leidinger recorded on May 15, 1933: “Meeting of presiding committee in the academy presidium: Willstätter sends a letter with his resignation as section secretary and from all academy commissions.”120

Willstätter had not followed the advice given him by his friend Fritz Haber on April 1 to avoid vacating any position voluntarily and await “extreme duress.”121 On the other hand, Haber himself had not stuck to his own advice, either: He resigned from his position as director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry in Berlin-Dahlem on April 30122 after having been forced to dismiss most of his staff—including Willstätter’s daughter Ida, who had worked for him as a research assistant—under the provisions of the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service.123

Now, following Haber’s example, Willstätter opted for what he called “privatization.” This step must have been all the more bitter as Willstätter had already yielded to antisemitic pressure and resigned from his university professorship in 1925.124 He did not expressly mention the incident at the academy in his memoirs, but he did include “academy meetings with my boring minutes” among the things that had ceased but that he did not miss “after Hitler’s seizure of power.”125

Willstätter was succeeded as section secretary by the physicist Jonathan Zenneck,126 who proved willing to acquiesce to the demands of the new regime and expressly defended discrimination against Jewish researchers in interactions with foreign colleagues.127 Zenneck concluded “Science and the Volk,” his speech marking the 178th anniversary of the academy’s founding, delivered on June 16, 1937, with a bold proclamation that “science is service to the people.”128 He did not mention that Jews in Germany were no longer part of science or of the people—because it was already common knowledge anyway.

Although Zenneck and his colleagues at the academy did have to deal with accusations leveled at them in 1940 by Otto Hörner, the lecturer’s leader at the Gau level, that they were trying to “preserve the Bayer. Academy as the last island of a reactionary anti-National Socialist republic of scholars,”129 this reproach essentially only referred to efforts on the part of the academy to preserve its rights to self-administration and to choose its own members. It had long abandoned its innermost raison d’être —from as early as 1933—by depriving individual members of this republic of their citizenship without scholarly justification or ousting them from their academic roles. A large question mark must be attached to the view that the academies of sciences and humanities were only gleichgeschaltet (synchronized with Nazism) at a comparatively late stage.130 As the events of spring 1933 show, the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities, at least, did not need any “Gleichschaltung” to be aligned with antisemitism. A large proportion of its members, and especially of its most influential members, had long been marching in step with the new holders of power. This explained the conclusion that Richard Willstätter had already been forced to draw at the time: “From the very beginning, the universities and learned societies were among the first exponents of this weakness.”131

IV

In mid-October 1938, the Prussian Academy of Sciences and Humanities complied with a request from the minister of science, education, and national culture, Bernhard Rust, and asked its three Jewish full members to resign, which they did.132 In the aftermath of the November pogroms of November 9–10, 1938, the Bavarian Academy—by then under its new president, Karl Alexander von Müller, who had close ties to the regime133—also pressured the Jews among its full members into leaving. On November 14, Richard Willstätter resigned from the academy together with the mathematicians Alfred Pringsheim and Heinrich Liebmann and the Indologist Lucian Scherman.134 Willstätter managed to emigrate to Switzerland at the beginning of March 1939 and find safe exile in Muralto near Locarno. On July 13, 1939, his name was also removed from the list of members of the Prussian Academy, to which he had belonged since 1914.135

After the demise of the Nazi regime, Willstätter could not be readmitted to the academy—he had died in 1942—and Einstein, now a permanent resident of the USA, had no interest in being readmitted. Quite soon after the American military government permitted the academy’s reestablishment on July 25, 1946, Arnold Sommerfeld was assigned the task of seeking to persuade Einstein to withdraw his resignation. Sommerfeld had always had a good relationship with Einstein.136 He was familiar with the letter the academy had sent to Einstein in April 1933 from Einstein’s publication of it in 1934, and he apologized on the academy’s behalf for the “highly inappropriate” request:

There was nothing we could do after the madness had suddenly broken out. … But now the madness is over, and the academy would like to send you its proceedings again. … A refusal on your part would be embarrassing for us, of course. I ask you to bury the hatchet and accept membership of the academy again.137

Einstein’s reaction on December 14, 1946, was friendly but firm:

Since the Germans murdered my Jewish brethern in Europe, I want nothing more to do with Germans, not even with a relatively harmless academy. It is different with the few individuals who remained steadfast within the realms of what possibilities there were. I heard with pleasure that you were among their number.138

Einstein’s stance influenced the academy’s approach to selecting new members in the early post-war years. It had to be acknowledged that the election of a scholar to the academy was now—in contrast to the time before 1933—not primarily an honor for the scholar, but rather for the academy, and one which not every scholar was necessarily eager to grant. This was expressly stated in the discussions that took place in the run-up to the the membership elections of 1951. In the mathematics and natural sciences section, ten possible candidates for nominations were discussed, one of whom was the mathematician Hermann Weyl (1885–1955). Weyl’s candidacy was being advanced chiefly by Heinrich Tietze, a section secretary of long standing.139 Weyl had emigrated in 1933 and found employment alongside Einstein at the Institute of Advanced Study in Princeton.140 Another mathematician in the section, Oskar Perron (1880–1975), who had been a member of the academy since 1924, was concerned that this context meant that electing Weyl could cause the academy to suffer the embarrassing fate of being rejected by a candidate again, as had already happened with Einstein. In a short memorandum addressed “To the mathematicians of the Bavarian Academy expected to attend the election session,” Perron explained his reservations about the election of foreign scholars and especially those who had been forced to emigrate from Germany. He also subjected the academy’s behavior during the Nazi years to a remarkably self-critical assessment. This is all the more notable given that Perron himself had proven to be a steadfast and courageous opponent of Nazism.141 His comments on the academy and the “Einstein case” speak for themselves and represent an appropriate conclusion to this study:

And now about the emigrants! To them, especially, we cannot say that we are an illustrious society. Because we deserted them all. We should not inflate our importance in front of them. We should crawl into the furthest mousehole and be ashamed. Personally, I am ashamed of myself too, and that’s the crux of my stance here. That is why I am in favor of strict reticence and modest flourishing in obscurity. For what did we, what did the academy do to save the persecuted scholars in the Third Reich? Nothing. We reach for the convenient excuse that we didn’t have the power, that we were not able. In truth, however, we did not try in earnest at all. Each of us simply shied away from the risk, perhaps because of the conflicting motive of being worried about our families. We were not heroes. But the emigrants had no choice, for the most part; they and their families had to bear the risk and endure endless suffering. That is why they are a good step above us—we who silently let everything happen—in the estimation of the world. Hermann Weyl is certainly among those who are prepared to forget (and not just because he coped relatively well personally, as the bright star he is, but because of his noble character), and he showed us when he was here that he is well-disposed toward us all. But I do not want to inflate my importance in front of him, and I’m afraid that his neighbor and colleague Einstein will say something to him like: “Well, well—the Bavarian Academy! You needn’t flatter yourself too much I offer my condolences. By the way, the gentlemen wanted to have me as well, but I gave them a smack.”142

Appendix

1

Inquiry from President Leopold Wenger to the Prussian Academy of Sciences, April 4, 1933 (copy),

PAW (1812–1945) (Prussian Academy of Sciences 1812–1945), II–III 57, p. 29, Archive of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Berlin.

Der Ausschuß unserer Akademie ist in die Behandlung des Falles Einstein darum einzutreten genötigt, weil Einstein korrespondierendes Mitglied unserer Akademie ist. Aus der im Namen der Akademie abgegebenen Erklärung des Herrn Sekretars Heymann ersehen wir, daß Herr Einstein aus Ihrer Akademie ausgetreten ist. Wir bitten, uns aus den in Ihrer Erklärung erwähnten Schriftstücken eine Abschrift der Austrittserklärung Einsteins zugehen zu lassen und ebenso, da dies für die Behandlung der Angelegenheit durch unsere Akademie nötig ist, wenn möglich eine Abschrift des Schreibens, in welchem Sie von Herrn Einstein Rechenschaft gefordert haben. Falls noch weitere Schritte von Ihnen in der Angelegenheit erfolgen sollten, so wären wir für jeweilige Mitteilungen sehr dankbar, sowie auch wir von unseren Beschlüssen Sie in Kenntnis setzen werden.

Für eine möglichste Beschleunigung wären wir bei der Dringlichkeit der Angelegenheit sehr dankbar.

Schließlich bitten wir um Mitteilung eines Weges, auf dem wir Herrn Einstein direkt ein Schreiben zukommen lassen können.

Hochachtungsvollst

L. Wenger

Präsident.

2

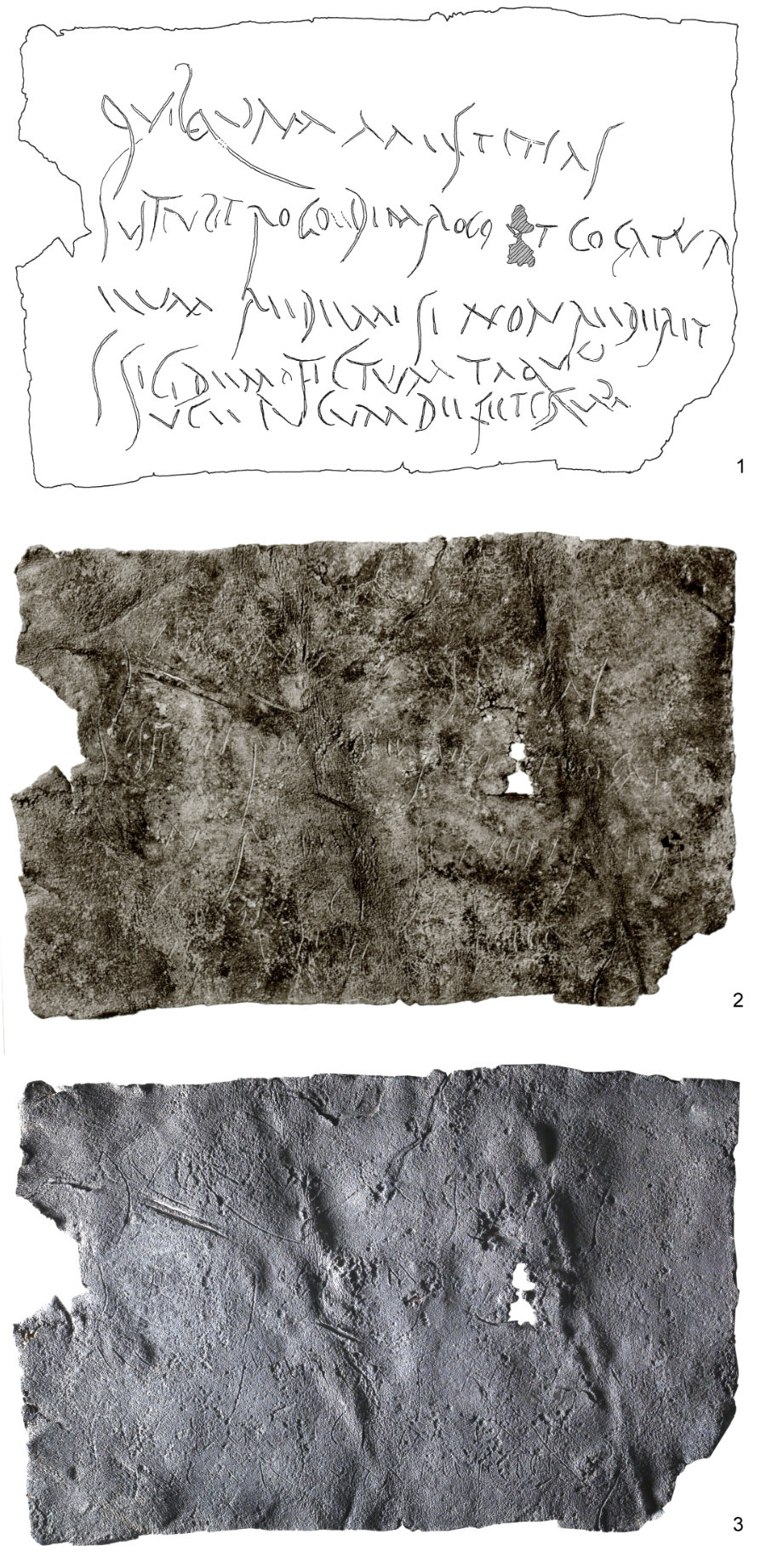

Letter from the Presiding Committee of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities to Albert Einstein, Munich, April 8, 1933.

Published in Albert Einstein, Mein Weltbild, Amsterdam 1934, p. 126–127; handwritten manuscript in Leidingeriana Iv.b.3.c, BSB.

Euer Hochwohlgeboren!

Sie haben in Ihrem Schreiben an die Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften Ihren Austritt mit den143 in Deutschland gegenwärtig herrschenden Zuständen motiviert. Die Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, die Sie vor einigen Jahren zum korrespondierenden Mitglied gewählt hat, ist ebenfalls eine deutsche Akademie, mit der Preußischen und den sonstigen144 Akademien in enger Solidarität verbunden145, sodaß Ihre Trennung von der Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften146 nicht ohne Einfluß auf Ihre Beziehungen147 zu unserer Akademie bleiben kann.

Wir müssen148 Sie daher fragen, wie Sie nach dem, was zwischen Ihnen und der Preußischen Akademie vorgegangen ist, das Verhältnis zu unserer Akademie auffassen.

149Das Präsidium der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

3

Decision of exclusion made by the Presiding Committee of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities, April 8, 1933,

manuscript, Leidingeriana IV.b.3.c., BSB.

Beschluß des Ausschusses der B. Akademie der Wissenschaften 8.IV.33:

Die Umstände, unter denen Herr Einstein seinen Austritt aus der Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften erklärt hat, veranlassen den Ausschuß, an die 2. Abteilung die Frage zu richten, ob sie nicht im Hinblick auf §11, Abs. 3 der Satzungen den Ausschluß Einsteins beantragen will.

4

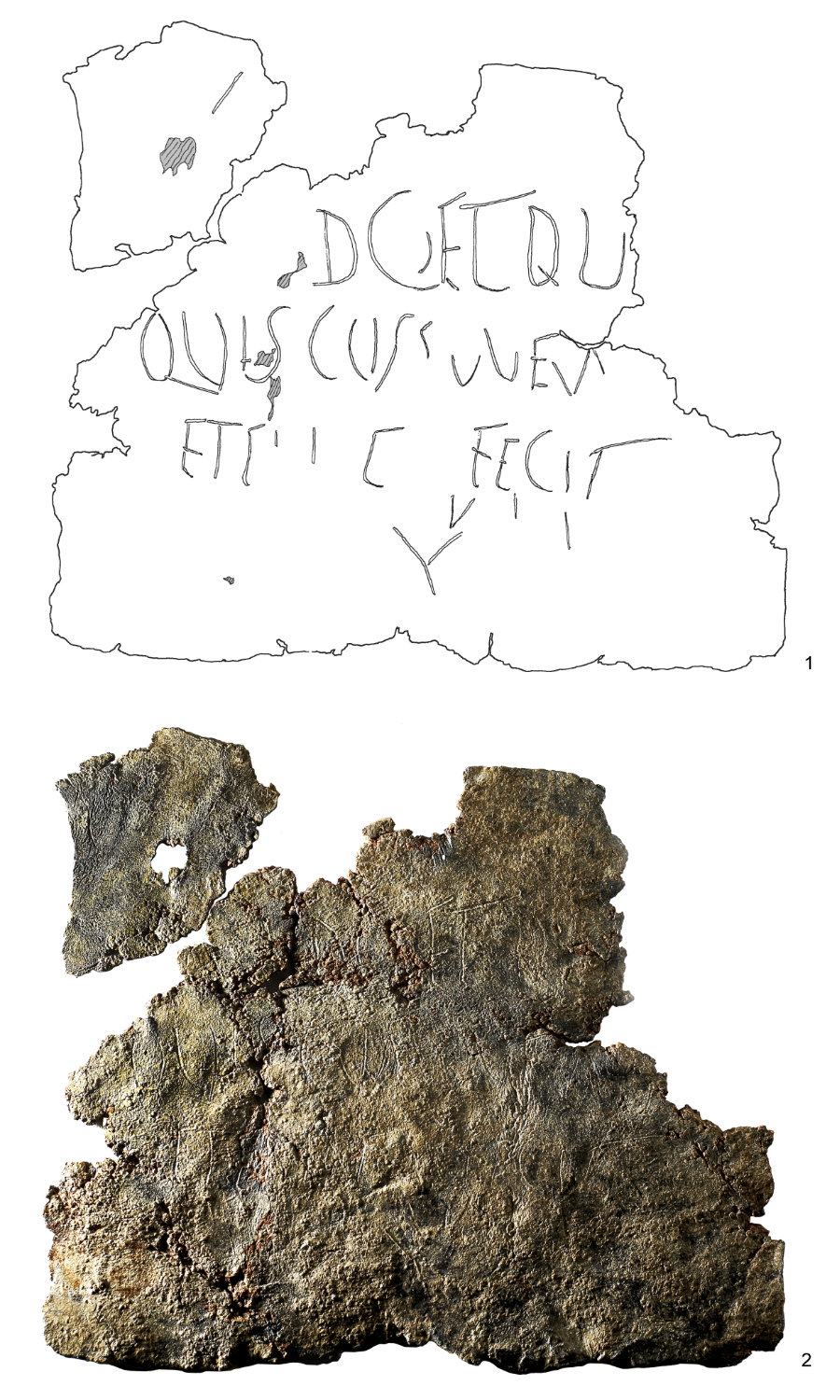

Albert Einstein’s letter of resignation, April 21, 1933,

Le Coq-sur-Mer, typed copy in Leidingeriana IV.b.3.c, BSB; published in Albert Einstein, Mein Weltbild, Amsterdam 1934, 127–128.

Ich habe den Rücktritt von meiner Stellung an der Preussischen Akademie damit begründet, daß ich unter den obwaltenden Umständen weder deutscher Bürger sein, noch in einer Art Abhängigkeitsverhältnis zu dem preußischen Unterrichtsministerium stehen wolle.

Diese Gründe würden an und für sich eine Lösung meiner Beziehungen zur Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften nicht bedingen. Wenn ich trotzdem wünsche, daß mein Name aus der Liste der Mitglieder gestrichen wird, so hat dies einen anderen Grund.

Akademien haben in erster Linie die Aufgabe, das wissenschaftliche Leben eines Landes zu fördern und zu schützen. Die deutschen gelehrten Gesellschaften haben aber – soviel mir bekannt ist – es schweigend hingenommen, daß ein nicht unerheblicher Teil der deutschen Gelehrten und Studenten, sowie der auf Grund einer akademischen Ausbildung Berufstätigen, ihrer Arbeitsmöglichkeiten und ihres Lebensunterhaltes in Deutschland beraubt wird. Einer Gesellschaft, die – wenn auch unter äusserem Drucke – eine solche Haltung einnimmt, will ich nicht angehören.

Mit vorzüglicher Hochachtung

gez.

A. Einstein

5

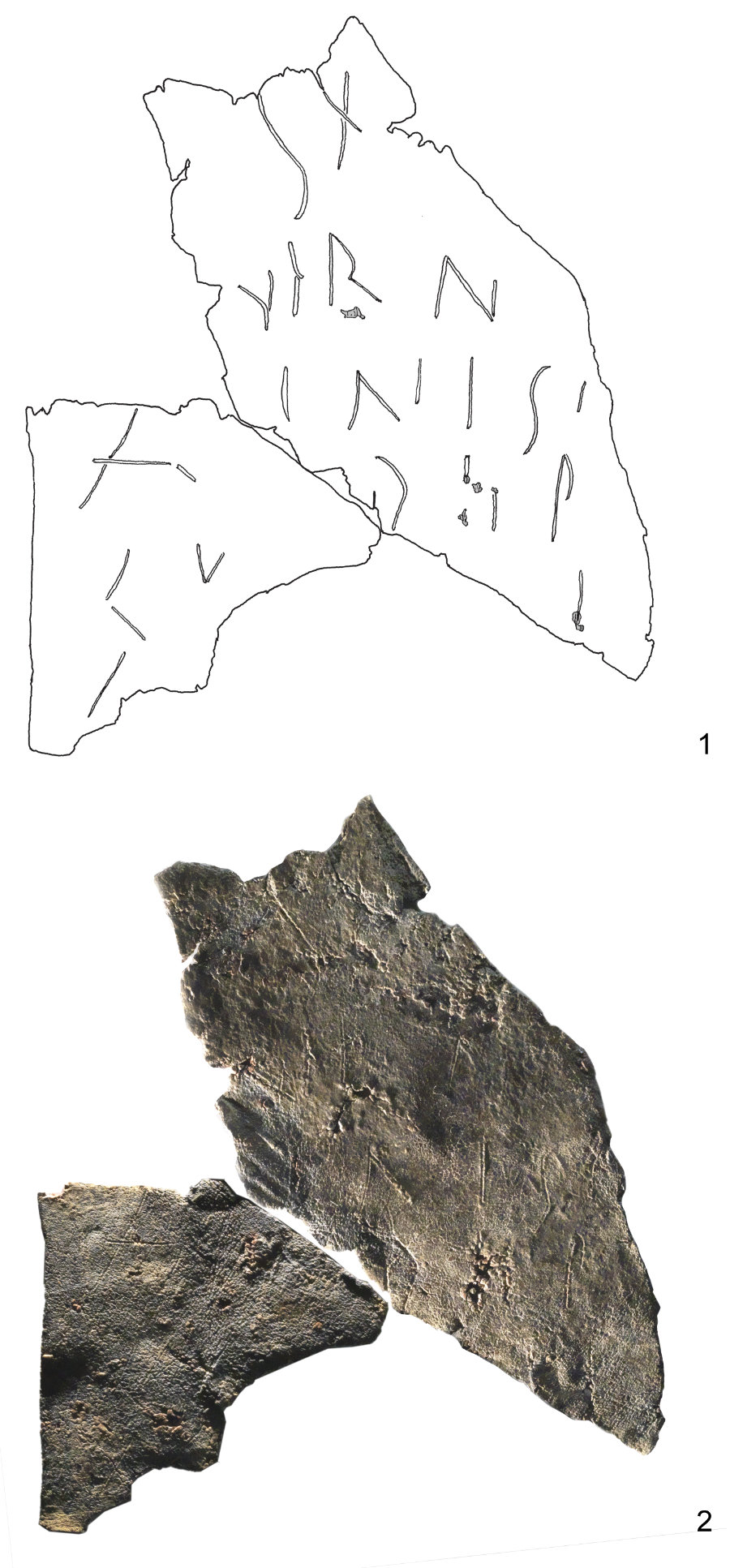

Message from Eduard Schwartz to the section secretaries, April 27, 1933,

copy for Leidinger as secretary of the history section, Leidingeriana Iv.b.3.c, BSB.

An die Herren amtierenden Klassensekretäre.

Ich beehre mich mitzuteilen, daß Herr Professor Dr. Einstein seinen Austritt aus der Zahl der korrespondierenden Mitglieder unserer Akademie erklärt hat.

E. Schwarz

Frauenholz