The Rhaetian Military Outpost in Eining and the Site Where the Tabellae Defixionum Were Found

At the very latest, the wooden cohort fort Abusina was erected on the high (southeastern) bank of the Donau in Eining during the reign of Emperor Titus (79–81 AD) as part of Governor C. Saturius’s efforts to fortify the Danube frontier by occupying the Ingolstadt basin.1 It was here that the new route along the north bank of the Danube crossed the river, linking Abusina with the Roman forts to the west. Isolated artifacts suggest that there may well have been an older military outpost here, however, perhaps a small fort similar to that in Nersingen.2 The oldest artifacts found date back to the Augustan Age;3 they could be relics of travel along the road from Augsburg along the Danube through the region around Regensburg, and from there to Bohemia—into the kingdom of Maroboduus.4

According to fragments of an inscription on the building, the camp, which covered 1.8 hectares (app. 4.5 acres), was built by a cohors Gallorum, generally assumed to have been the cohors IIII Gallorum. The relatively recently discovered military diploma AE 2007, no. 1782, however, provides evidence that the cohors II Gallorum was present in Rhaetia after 86 AD, and, taken together with the fragments of the inscription in Eining—of which the numerals are only partially extant—it is thus possible that the reference is in fact to this cohort. Between 107 and 116 AD, the cohors III Britannorum from Regensburg-Kumpfmühl moved into the castellum in Eining.5 During the first half of the second century AD, but after 125 AD, the fort was reinforced with stone.6 The Britannic cohort maintained their station in Eining even beyond the upheaval of the third century. During the tetrarchic period, significantly less expansive fortifications covered the southwestern corner of the mid-imperial quadrangle. According to the Notitia dignitatum, troops were still stationed in Eining in the fifth century AD. Gschwind suggested that the location had been abandoned around 430 AD,7 but more recent scholarship has estimated that this might not have occurred until somewhat later in the middle third of the fifth century AD.8

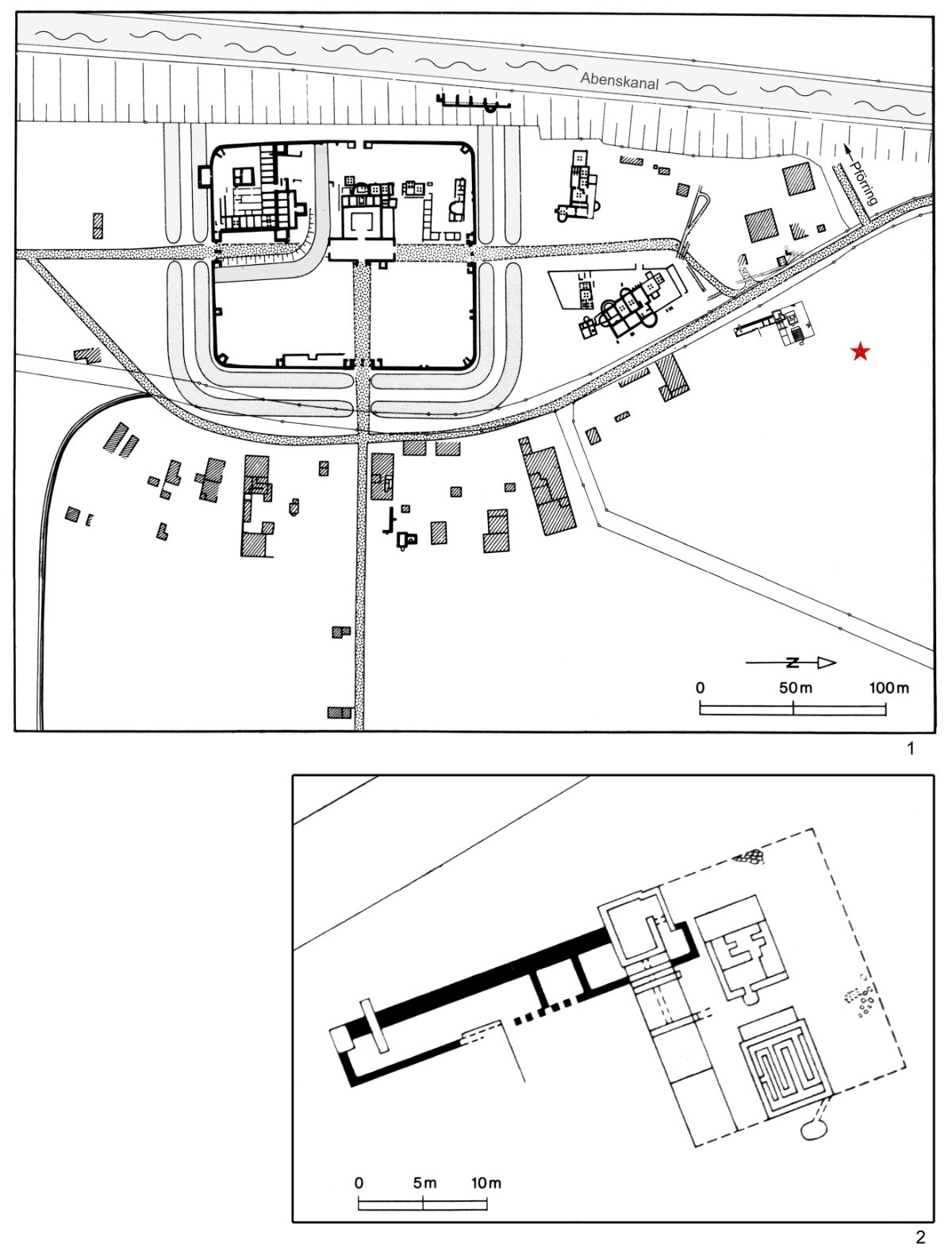

The fort and the northern vicus, looking towards the north. The location where the tabellae defixionum were found is marked with a star.

A considerable vicus [civilian settlement]—at present known primarily from scattered finds and aerial photographs (image 1)—developed along the road that paralleled the Danube, which curved around the east side of the fort.9 With the narrow end perpendicular to the road, these long rectangular building complexes were primarily built along the eastern side; over time, some of these were built of stone or at least had stone foundation walls.

In the roughly triangular area defined by the northern side of the fort, the road to the east through the vicus, and the steep embankment down to the Danube, there were a number of large stone buildings, including a bath and a building referred to as a “villa” or “guesthouse” with hypocaust heating and apses. It can thus be concluded that it was in this part of the vicus, in front of the porta principalis sinistra, where the public buildings stood. At the northern end of this area, these may have included religious temples, which would correspond to the square foundations evident in some aerial photographs.10

The southern end of the encampment village is marked by a cemetery beginning some three hundred meters from the fort’s southern portal. The northern limits of the settlement, with increasingly scarce findings, were established in 1999 in rescue excavations related to new construction two hundred meters north of the fort’s northern gate.11

The Location Where the Tabellae Defixionum Were Found

The lead curse tablets which are the subject of this study were found in the 1980s with the help of a metal detector in what was once the northern part of the vicus and was then a field used for agriculture.12 The location at which they were found is to the east of the Roman road, only sixty meters east of the point at which the road from Pförring crossed the Danube, here went up and over the edge of the plateau to join the Danube Road (image 2.1).

1) Abusina/Eining fort and vicus according to excavation finds and aerial photograph analysis. The area in which the curse tablets were found along the northern periphery of the settlement is marked with a star.

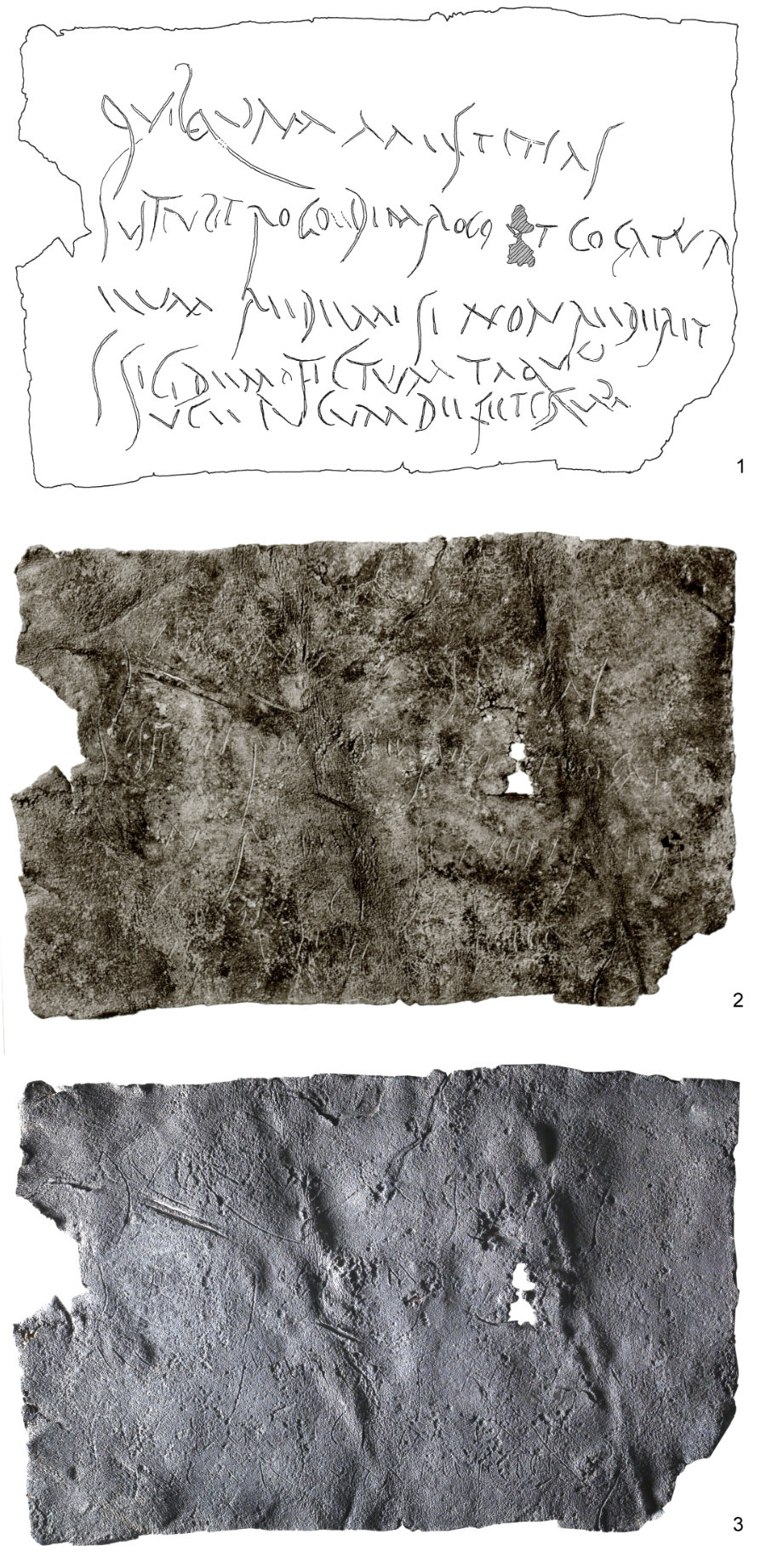

2) The complex of buildings discovered by P. Reinecke in 1915/16 east of the road in the northern part of the vicus.

In 1915–1916, Paul Reinecke conducted an excavation of the area around this intersection, just some thirty meters to the southwest of where the curse tablets were found. He reported briefly on the excavations in the autumn of 1915 which focused on the northern portions of this area in the Römisch-Germanisches Korrespondenzblatt.13 The succinct, unillustrated description of what they had excavated can only be understood when juxtaposed with later illustrations of the excavation (image 2.2). Reinecke’s interpretation of the excavated remains as a “small farmstead with agricultural character” hardly makes sense given its location which more recent research has definitively shown it to have been within the vicus belonging to the fort. The archeologist noted several phases of building evident in the floors of the excavated structures. Together with the southern wing, which was first excavated in 1916, the complex consists of a stone cellar which opens to the north; a narrow stone building (25 m long, 5 m wide) was attached on the south side. The western wall of this narrow wing was a particularly massive stone wall; the other walls were considerably thinner, and the building’s interior was divided by two internal walls. The cellar had a wooden floor, which, rather unusually, had been covered with a layer of mortar. The building that rested upon this foundation was certainly half-timbered construction, as evidenced in the debris from the fire that was dumped into the cellar. On the eastern side of the cellar, there is extant evidence of the floors of three additional rooms that had neither outer stone walls nor wall trenches. It can thus be presumed that the construction here rested on sleeper beams. To the north of this framework of the cellar and rooms, there were two separate but aligned sets of nearly square walls, approximately 7.5 x 6 m in size. Reinecke described their inner structure thus:

The second building with the living space displays in the back (to the east) a nearly square, walled room, the floor of which, for the sake of keeping it dry, was built over a hypocaust-type (without praefurnium) cellar (stone panels over ducts formed by low dry-pack walls). To the west lay a deeper room, the kitchen and praefurnium of the square living room to the west, two quarters of the floor of which could be heated (in two diagonally opposite corners) (a sort of duct heating, the channels of which were simply carved into the sand floor, only partially reinforced by poorly constructed dry-pack-wall-type stone piles).14

It is practically impossible to clarify the particulars of the archeological find based on this description.

To the north and west of the quadrangle, there was a courtyard paved with stone, but the outer limit of this courtyard was not found. The archeologist at the time thus considered the possibility of there having been a fence or hedge. An area leading up to the ancient road, just in front of the complex to the west and about ten meters wide, was covered in a light layer of gravel. According to the finds, which included the youngest coins minted by Gordian III and Philip the Arab,15 Reinecke dated the building complex to the third century AD.

The total character of the structures inventoried does not fit into the general pattern typical of Rhaetian settlements dominated by strip-house construction.16 The massive perpendicular stone wing extends over the width of several typical strip-house lots. For this reason, it seems beyond a doubt that this shape corresponds to an especial function of the not yet completely studied complex. The building’s location along the northern periphery of the vicus—and, even more so, the fact that the curse tablets were found nearby—can be read as additional evidence for this supposition. In regards to the massive transverse wing, but also in the many divisions of the complex and the courtyard area, this structure resembles the sacred site dedicated to Isis and Magna Mater in Mainz that was discovered and excavated between 1999 and 2001.17 There, too, a number of leaden curse tablets were found scattered throughout the entire area.18 According to the observations of the excavator, these tablets were not directly related to regular cultic rites. Instead, the relationship of these goddesses to sorcery and death likely made their religious site attractive for practicing forms of magic.

Candleholder unearthed in P. Reinecke’s excavations in 1915/16 in the buildings in the northeastern part of the fort’s vicus. Scale 1:2.

This supposed religious character of the structure in Eining may be further evidenced in an unusual, elaborately formed bronze candleholder, which was the only artifact pictured in the context of Reinecke’s report (image 3). Whether or not the “assorted tin fibula” were found in numbers exceeding what one might expect or might suggest their having been left as sacrificial offerings is not clear, given the brevity of Reinecke’s account.19

The curse tablets, floor plan, and excavated artifacts do not provide conclusive evidence as to whether or not the building site that Reinecke excavated in part served a religious function, perhaps even as a sanctuary to Isis and/or Magna Mater. This remains, however, a distinct possibility, which future studies will hopefully help to clarify.

Bernd Steidl

The Lead Tablets

Due to the irregularity of the shape and size of the letters, the in some instances very shallow groove of the engraving, lacunae in the text due its fragmentation, and the advanced state of oxidation, it was exceedingly difficult to decipher the text of the lead tablets.20 The disintegration of the metallic lead had already resulted in multiple yellow and red oxidation spots. The lead tablets were studied and documented with attention to the following characteristics: condition, dimensions, text, dating, peculiarities. The sketches were made by the author [J.B.].

The edition is organized in the following chapters:

- literal transcription of the text as read (so-called “diplomatic transcription” that distinguishes between majuscule and minuscule letters); textual analysis. The critical characters used here include: […] spaces; <…> emendation, (…) the resolution of abbreviations.

- edited transcription with spaces between words, punctuation, and capitalization of proper nouns, interpretive additions (…); translation; commentary on the contents and language used; interpretation of the contents. Incomprehensible text is indicated by capital letters.

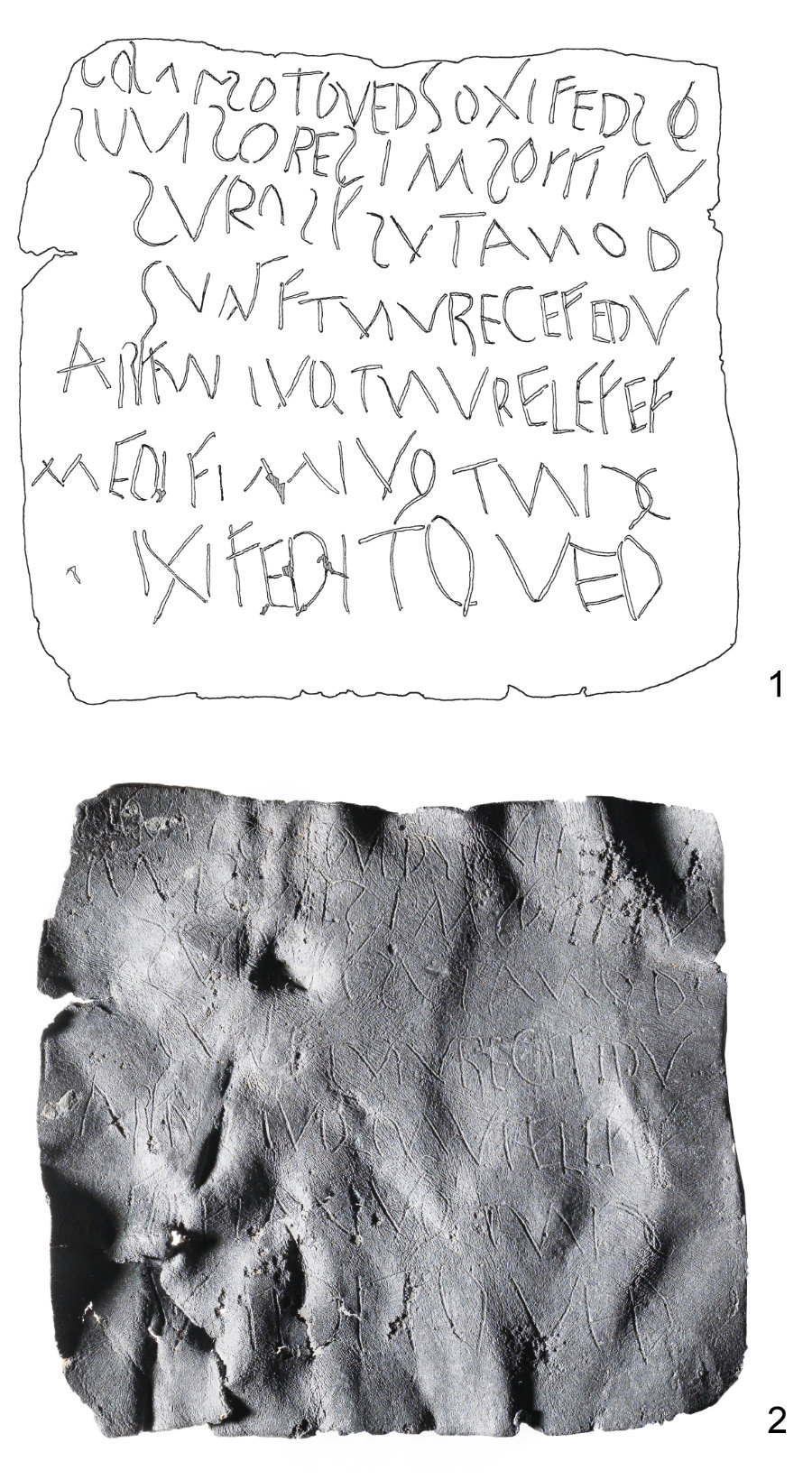

DT Abusina 1

ASM Inv. 2006.2173. Width x height: 10.5 x 6.5 cm. Height of the letters: 6–8 mm

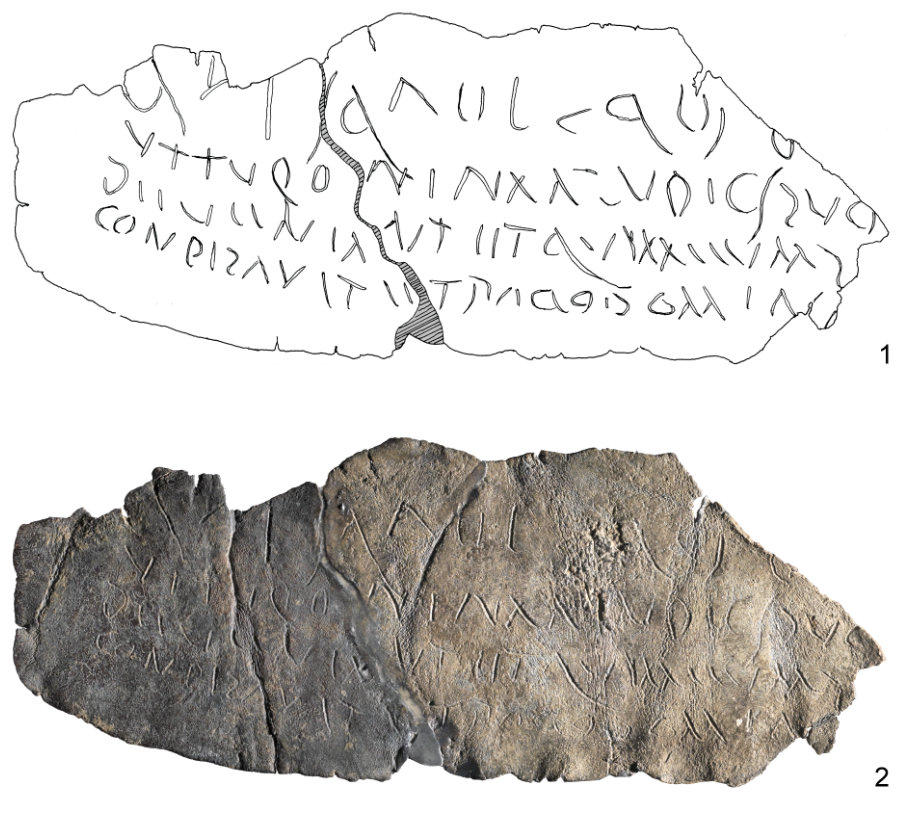

Lead tablet DT Abusina 1. 1) Sketch; 2) Photograph of the condition prior to restoration (1982); 3) Current condition. Scale 1:1.

Lightly uneven as a result of having been folded; Surface unoxidized; missing fragment on left edge that does not affect the lettering. Small hole in the middle. Writing is preserved only on the verso (see below). In the right corner of the recto, the lead has begun to oxidize as evidenced in yellow and red spots.

Script

Older minuscule cursive with the typical shape of the letter e in which a double stroke leans to the left and long codae (horizontal strokes) in the letters q and r. The letters A, D, G, M, and N retain the majuscule form. The script resembles that of the curse tablets found within the sanctuary of Isis and Mater Magna in Mainz down to the very details.21 No doubling of consonants (i.e., gemination). Dated: Mid to late first century AD.

Additional Information

The analysis is based upon a recent flash photograph, older photographs, a previously completed sketch, and recent detail photographs. In some cases, the older pictures reveal more details than the newer ones. The sketch reproduced here combines the results of these various readings.

Diplomatic Transcription

1 quisquam mestitias

2 sustulit rogo [..]dim rogo [u]t cogatur

3 eum redemi si non rederit

4 sic idem fictum taqua

5 sucepu cum defictcsione

Textual Analysis

The words are separated by remarkable spaces.

Lacking double consonants: 3 redemi = redde mi(hi), rederit = reddiderit

5 sucepu: p is formed with a hasta (vertical stroke) and a downward-leaning second stroke similar to the manner found in some of the tablets from Mainz.

Edited Transcription

1 Quisquam m(a)estitias

2 sustulit? rogo, [i]d<e>m rogo, ut cogatur.

3 eum red(d)e mi. si non red(d)e<d>erit,

4 sic idem fictum, ta(m)qua(m)

5 susceptum cum defixione

Translation

“Has anyone endured (such) misery? I ask, just as I ask, that he might be compelled. Give him back to me. If he does not give him back, I will banish him, just as if he had been overcome by a curse.”

Commentary

The side which bears the text must have been the verso, for the text assumes the salutations addressed to the deity and the mention of the object stolen.

Characteristic of Vulgar Latin are the monophthongization from ae to e, the lack of gemination, the incorrect form fictum instead of fixum, and the exclusion of the nasal in taqua instead of tamquam.

Line 1: The use of the pronoun quisquam is grammatically correct, if a negated interrogative clause is assumed. One expects something like tales maestitias.

Line 2: [.]dim cannot be completed with a Latin term. Presumably, it is meant to read idem as in line 4. Particularly noticeable is the emphatic repetition of rogo… rogo. It is only line 5 that makes clear that the text refers to a male (sucepu = susceptum), but this must have been already clearly stated on the recto.

Line 3, which initially seems to read eum redemi (I have bought the freedom of…) is contradicted by the subsequent si non rederit. In addition, the clause ut cogatur would then be left without the necessary complement. A predicate for fictum, for example, faciam, is missing.

Line 4: idem is either to be understood as a substitute for ego quoque or as a grammatically false accusative instead of eundem.

Line 5: Even if we presume Vulgar Latin spelling, the classical pronunciation of the word cannot be determined with certainty. My preliminary suggestion is susceptum, which, together with cum defixione, forms a cogent phrase: “overcome by a curse.” The orthography of the classical word defixio is beyond the scope of the author’s knowledge: defictcsione.

Interpretation

The text on this side implies that the delinquent and his infraction have been named on the other side. This side must thus be the verso. The wording expresses more strongly than other extant curse tablets how the loss has taken an emotional toll on the author. It begins with the lamentation over the loss of the object, which cannot be more closely determined. The weight placed upon the lost suggests more that it is about a person than a material object. It is followed by the demand for the return and the threat of a curse, the extent of which is expanded in the grammatically incomplete added phrase. The author of this primarily Vulgar Latin text has insufficient language skills to use the expression properly.

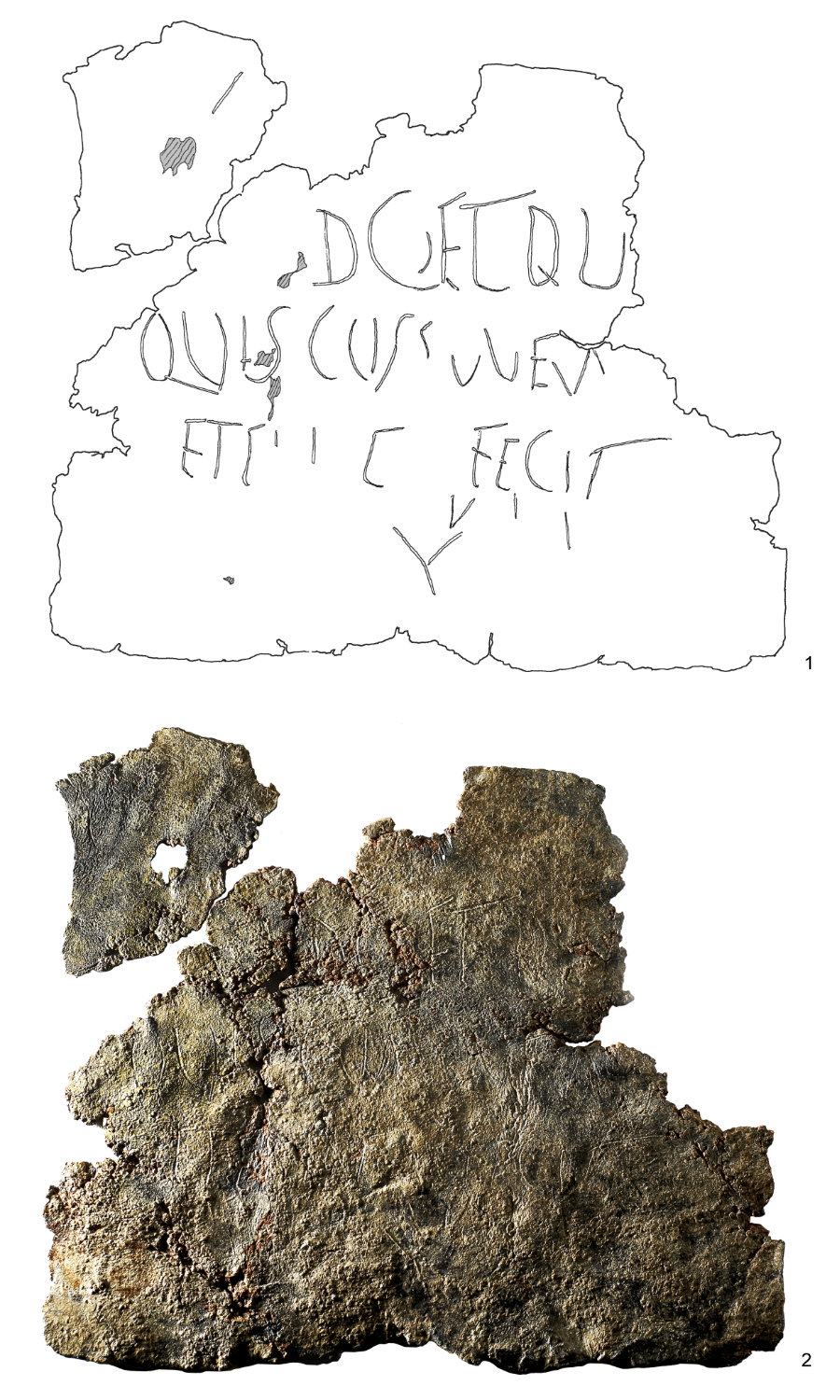

DT Abusina 2

ASM E. No. 1981/22. Width x height: 9 x 3.5 cm. Height of the letters: 3–4 mm

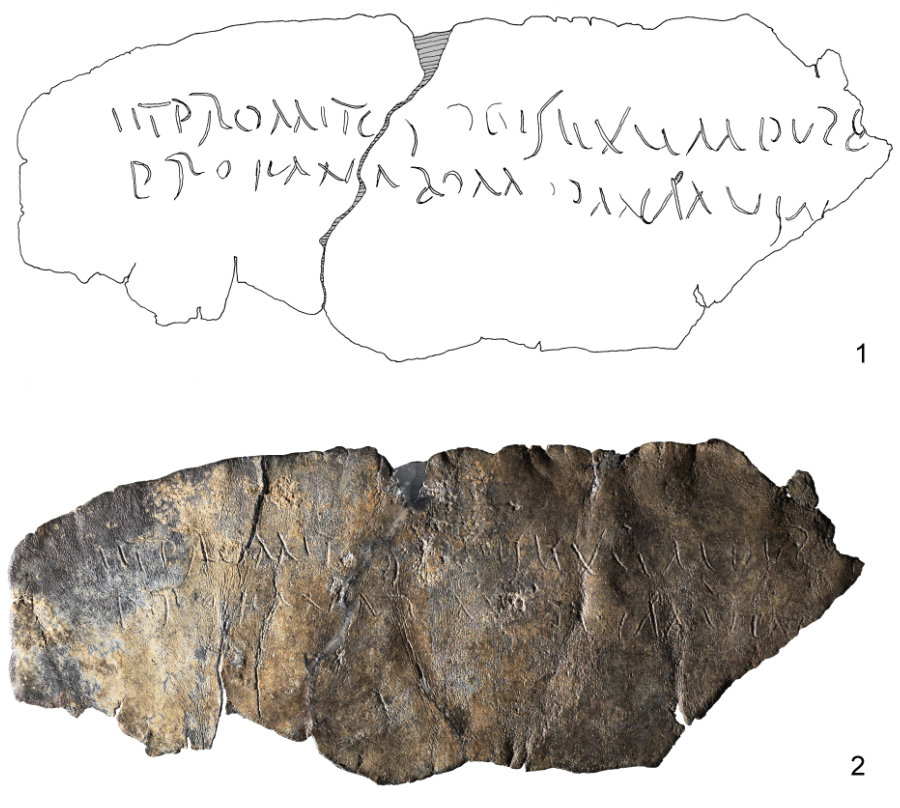

Lead tablet DT Abusina 2, front (recto). 1) Sketch; 2) Photograph. Scale 1:1.

Lead tablet DT Abusina 2, back (verso). 1) Sketch; 2) Photograph. Scale 1:1.

The writing has been adapted to the irregular form along the upper, left, and right margins. A fragment of indeterminable size has broken off the right side. The tablet is broken and has been glued back together somewhat inexactly; some smaller pieces are missing. As a result, the right half of the line 3 has been shifted upward somewhat. The glue has obscured one or two letters in two spots.

Script

Older minuscule cursive like DT Abusina 1; thus a similar date, but rougher and mostly without spacing between words. The letter D has a majuscule form and an unzial shape open to the left; u and e are distinctively different. No gemination of consonants.

Additional Information

After writing three lines on the recto (3 lines), the author turned the originally strip-shaped tablet over along the long axis, so that the damage documented here is mirrored on the other side, as well.

Diplomatic Transcription

Recto:

1 quis qAui[…] quis[…

2 uttudominaaludiosluo[…

3 deueniant et quimeuml[…

4 conpilauit et rogodomina[…

Verso:

5 etpromito […]cesexempulo[…

6 prosuanabom[…]mumus[…

Textual Analysis

On the right end of the lines, so much text has been lost that it is impossible to conjecture the context. In line 6, the word division is uncertain.

Line 1: very large letters. The fact that quis is thrice repeated and the second u is turned backwards and then repeated correctly suggests a faulty mastery of writing.

Line 2: From this point, the letters are smaller and more regular in size, presumably written by another author. Only the d in domina is wrong. The l in ludio is uncertain due to advanced oxidation. Two vertical strokes have been determined after closer observation to be cracks in the lead. They are thus omitted from the sketch.

Line 3: The end of the word deueniant is somewhat misaligned due to the fragmentation of the lead tablet.

Edited Transcription

Recto:

1 quis quis quis […

2 ut tu, domina, a ludio SLUO[…

3 deveniant, et qui meum l[…

4 conpilavit, et rogo, domina[…

Verso:

5 et promit(t)o[…]CES exempulo […

6 pro sua NABOM[…]MVMUS […

Translation

Recto:

1 “Who, who, whoever […

2 that you, (my) lady, from the scoundrel […

3 they should arrive, and who my […

4 has stolen, and I ask, (my) lady […”

Verso:

5 “and I promise… (sacrificial offerings?) of the highest quality […

6 for his… […

Commentary

Line 1: The use of quis or quisquis is typical for curses directed at unknown delinquents.

Line 2: The phrase ut tu, domina marks the beginning of the appeal to the deity. This domina could refer to Victoria, who is known to have been worshiped in Abusina. Female deities referred to as domina include, among others, Mater Magna (Mainz), Isis (Baelo Claudia), and Terra (Carthage). The word ludius (player/actor, scoundrel) is more likely a deprecatory epithet than a proper name; a ludio can be interpreted as the wish to have something returned from the delinquent. No interpretation can be offered for SLUO. In Latin, only two consonants can follow the letter s, p, or t. Neither of these can be read in this instance.

Lines 3–4: The verb deveniant is associated with multiple negative connotations (in manus alienas, in potestatem), and thus refers here to the wish as to what should happen to the delinquents—in the plural here, which is often used to include a potential confidant to the infraction. The stolen object must have been named in the gap, the length of which is indeterminable, in et qui meum l[… / …]conpilavit.

Line 4: The verb conpilare (to steal, to plunder) is classical, but rare, and used here, as in other curses concerning theft, in place of furari, which Vulgar Latin typically avoids as a deponent. The phrase et rogo, domina repeats the request for help and could be completed along the lines of “that you grant my request before something is promised on the reverse side in return.”

Line 5: In et promito, the doubling of the consonant is missing; it should be promitto. The return offering should consist of multiple objects: ]ces. – exempulo: although etymologically correct, there is no established anaptyxis for exemplo, which could refer to the extraordinary value of the offering promised in return. The orthography of the consonant combination pl is uncertain. In addition to the common templum, there are three documented instances of tempulum or tempulinum (AE 1940.209; CIL VI.831, CIL XII.649). In discipulus, the anaptyxical form is the standard, in disciplina, the syncopated form is established; in addition, there is one documented instance of discipulina (CIL VIII.14464). If one were to suppose another division of the words, one might conjecture that pulo is pullo(s) (“boy” or “black”) with a lack of gemination and to be read with sex, but this leaves a senseless em between them. Another division results in sex empulo, but this, too, does not correspond to any known word. Other words that end with -ulo—like discipulo, epulos, famulo, manipulo, populo, scopulo, scrupulo, titulo, tumulo—are not fitting alternatives in regard to either orthography or meaning. Similarly, any attempts to infer shifts typical for Vulgar Latin (e.g., e = ae or the dropped h) failed.

Line 6: Aside from the easily read word pro, the line is indecipherable. In the middle of the line, the strokes preserved are not sufficient to support the fitting conjecture of ab om[nibus]. The same can be said for another guess: abominamur.

Interpretation

Despite the fragmentary nature of the object and the partly undecipherable text, all of the components of a curse in response to theft are present. A deity addressed as domina is asked for help; a delinquent is named, in this case with an epithet; the infraction is outlined along with a desire for revenge and the request that this revenge might be fulfilled, and an offering is promised in return.

Unlike DT Abusina 1, the text in this case is classical except for the lack of consonant gemination.

DT Abusina 3

ASM Inv. 2006.2172. Width x height: 5.5 x 5.0 cm. Height of the letters: 3 mm

Dr. Steidl has already presented the text on this tablet elsewhere.22

Lead tablet DT Abusina 3. 1) Sketch; 2) Photograph. Scale 1:1.

Very well preserved. A few cracks on the left margin and lower section, a dent in the upper section, no loss of text.

Script

Majuscule letters, which—especially notable in the N—lean to the left, as is typical for retrograde script. The progressively smaller text and tighter line spacing from line 7 to line 1, along with the significantly tighter spacing of the letters at the end of the text (= left end of line 1), are evidence of the fact that this text is indeed a retrograde writing sample. Only a few letters are written in mirror image: S; the letter L is only upside down in line 2. It is not possible to date the object based on the script.

Additional Information

Retrograde writing to be read from the end of line 7 to the beginning of line 1. Except for lines 4–5, the word and syllable endings are observed.

Diplomatic Transcription

1 SOLAMSOTOVEDSOXIFEDSOL

2 LVNSORESIMSOLLIN

3 SVROLFSVTANOD

4 SVALFTNVRECEFEDV

5 ARFNIIVQTNVRELEFEF

6 MEDIFIMIVQTNIS

7 IXIFEDITOVED

Textual Analysis

Line 4: Fla(v)us: orthographical mistake or careless pronunciation.

Line 5: fefel(l)erunt, with lack of consonant gemination as in DT Abusina 1 and 2.

Line 6: mi: established classical abbreviation of mihi.

Edited Transcription

7 Devoti, defixi

6 sint, qui mi fidem

5 fefel(l)erunt, qui in fra-

4 ude fecerunt: Fla(v)us,

3 Donatus, Florus.

2 Nillos, miseros, nul-

1 los, defixos, devotos, malos

Translation

“Cursed, banished they should be, those who abused my trust, and who acted deceptively: Flavus, Donatus, Florus. (I curse) the nobodies, the miserable, the nobodies, the banished, the cursed, the malignant.”

Commentary

Line 7f: Rarely is the terminology of cursing so directly and thoroughly employed. It is repeated at the end of the text.

Lines 2–1: nillos … nullos: the negated pronoun is used as an adjective: “empty, worthless”; the accusative can be understood if a word like defigo has been elided.

Interpretation

The text, written in the retrograde method and intended to convey magical powers, is notable for a number of stylistic repetitions and alliterations; one might speak here of a popular rhetorical style. The text begins and ends by putting a curse upon three people, who are asyndetically named in the middle section of the text. The reason for the curse is disloyalty, which the text emphatically states twice—with both fidem fallere and fraudem facere. It does not, however, list any further details.

DT Abusina 4

ASM E. No. 1981/22. Width x height of large fragment: 11 x 9 cm. Height of the letters: 7–8 mm

Lead tablet DT Abusina 4, front (recto). 1) Sketch; 2) Photograph. Scale 1:1.

Lead tablet DT Abusina 4, back (verso). 1) Sketch; 2) Photograph. Scale 1:1.

Condition

The tablet is broken into three parts; the smallest piece has a broken edge that matches that of the largest, so that one might speak of two fragments. In addition, considerable pieces from the upper and right-hand margins are missing. Yellow and red oxidation spots have roughened the leaden surface.

Script

Majuscule lettering. Given the similarities with capitalis rustica, the text can be dated as relatively late, at least to the third century AD.

Additional Information

Four lines of text of decreasing height and line spacing.

Diplomatic Transcription

Recto

1 DC ET QV […

2 QVISQVIS.. E[…

3 ET.. FECIT […

4 Y

Textual Analysis

DC: indecipherable, perhaps it could be read as OC=hoc.

Edited Transcription

1 (hoc) et qu<is…[

2 quisquis… […

3 et… fecit […

4 Y

Translation

1 “this (?)… and who (whoever?)

2 whoever… […

3 and… has done […”

4 [.]

Commentary

Lines 1–3: The pronouns presumably introduce clauses that name the unknown delinquents and their infractions. The deed is characterized with fecit.

Verso

Four lines of single, indecipherable letters; majuscule script in lines 1–3, minuscule script in line 4.

Interpretation

Given the numerous parallels in texts that name unknown delinquents, it can be safely assumed that this artifact is also a curse tablet.

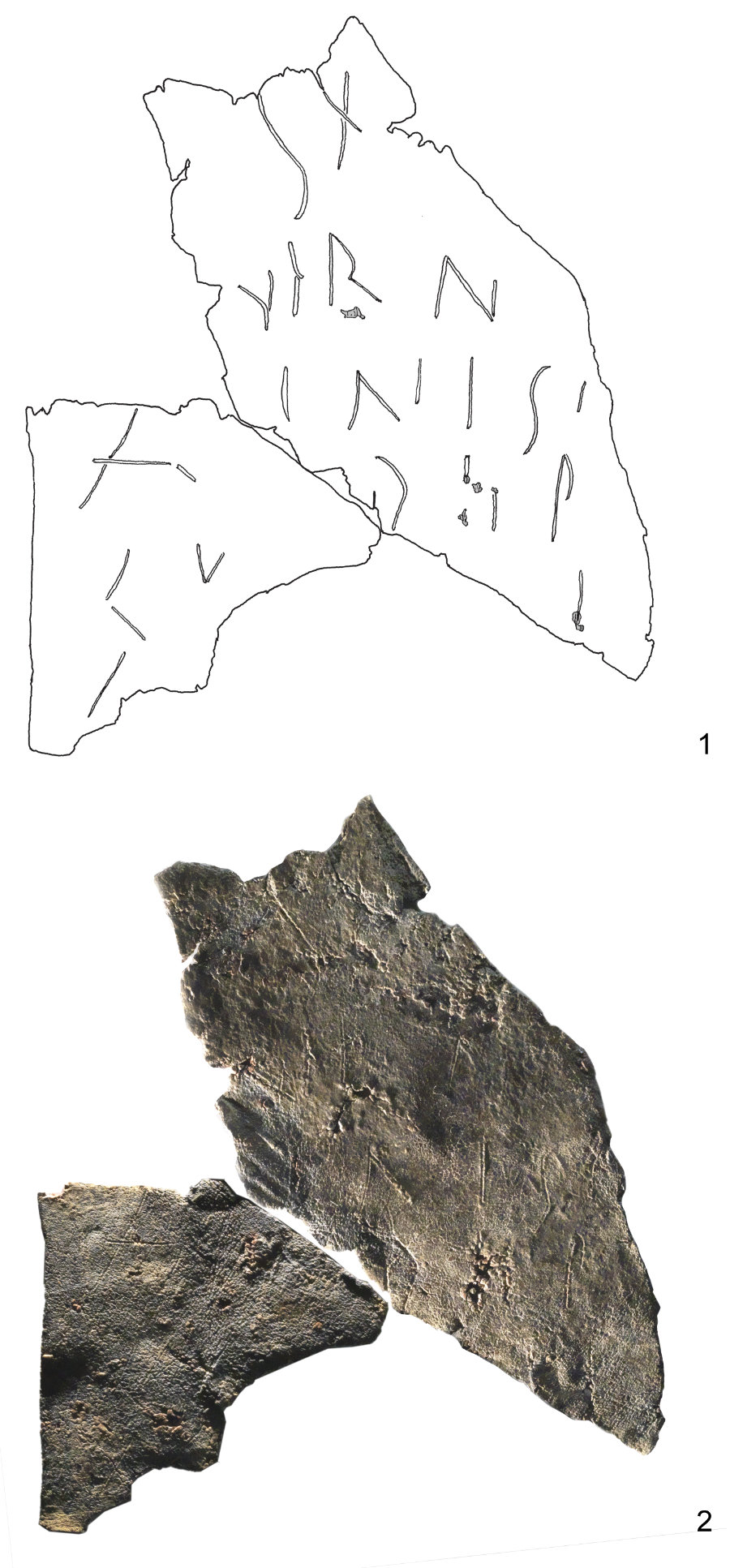

DT Abusina 5

ASM E. No. 1981/2. Width x height: 6 x 7.4 cm. Height of the letters: between 3.5 and 1.4 cm

Lead tablet DT Abusina 5. 1) Sketch; 2) Photograph. Scale 1:1.

Condition

Two fragments of a larger tablet that lack exact matching edges. The corner of one outer margin is preserved.

Script

Majuscule, date indeterminable.

Diplomatic Transcription

1 S X

2 V I R (?) N

3 X… I NISI

4 L (?) P

Text Analysis

The letters are written with considerable spaces between them.

Edited Transcription

1 SX

2 vir (?) N

3 X. I nisi

4 L (?) P

Translation

“Man… if not…”

Commentary

If the vir in line 2 is a reference to the delinquent, this text could be a curse directed at an unknown individual. Line 3: nisi: Parallel texts suggest the possibility that the curse was to be suspended if the stolen object were returned.23

Interpretation

Even the scant remains of the inscription allow for identifying it as a curse.

Assessment

Magical rites, with which it was possible to call upon the gods and demons in order to acquire power over other individuals, to punish them for their behavior, or to eliminate them as potential competitors from professional situations, chariot races, or romantic affairs, had been imported into Greece from ancient Egypt and the Near East and from there had spread throughout all areas of the Roman Empire.

Evidence of these practices is provided by five lead tablets—only one of which is preserved completely—found near the civilian settlement (vicus) just outside the Roman fort Abusina and two curse dolls made of clay, which were pierced multiple times with needles to symbolize the curse. They resemble the more or less contemporary figures found within the sanctuary of Isis and Mater Magna in Mainz.

The lead tablets and the curse dolls can be dated to the period between the founding of the fort in 80 AD and the destruction of the vicus in 260 AD. They cannot, however, as stray finds be assigned to any particular settlement strata. As a result, the dating must be based on the form of the script, the orthography, and the language used. The texts written in minuscule certainly stem from the second half of the first or beginning of the second century AD. The majuscule texts can be dated to the second or third century AD based on their use of language.

All the texts incorporate the sort of deviations from standard Latin that are typical for areas on the periphery of the Roman Empire. One peculiarity is the lack of consonant gemination.

Based on the material of the tablets themselves and the text, there is no doubt that they all served to place a curse on one or several wrongdoers. Given the distinctive differences in the script and composition, it is clear that the texts were composed by different authors, all of whom had only a basic grasp of the typical characteristics of curse texts. Although one author was acquainted with the technique of retrograde script, none of the authors used the standard phrases associated with sorcery. Like the roughly contemporaneous curse tablets found in the sanctuary of Isis and Mater Magna in Mainz (DTM)—similarly situated along the periphery of the Roman Empire, the tablets found in Eining lack magical symbols or images. Apparently the authors were not priests, sorcerers, or professional scribes, but rather lay people. There is little to suggest whether they might have been male or female, free or enslaved. The intense emotion that implies a sense of powerlessness found in one of the texts (DT Abusina 1) suggests that this text might be most likely have been written by a woman.

The reasons given for the curses are kidnapping, theft, infidelity, and fraud. These infractions were all punishable under the law, assuming that the injured party was entitled to pursue litigation. The fact that the authors did not do so could mean that they were not Roman citizens or were women. The case of the unknown wrongdoer is a special case. In such an instance, appealing to a supernatural power was the first line of defense.

The contents of the texts do not refer at all to the military encampments or its residents. The only geographical reference is implied in the use of domina to appeal to a female deity, which could refer to Victoria, who was venerated together with Mars in a nearby temple. Steidl’s recent research on the circumstances surrounding these artifacts, however, also allows for the hypothesis that, as in Mainz, Mater Magna was venerated here and such ritual curses might have called upon her. Although the goddess Fortuna was venerated in Abusina, as well, the evidence of this cult is dated to a later period.

Sigla

AE: L’Année Épigraphique (Paris, 1888ff.)

ASM: Archäologische Staatssammlung München

CIL: Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum

IBR: F. Vollmer. Inscriptiones Baivariae Romanae: sive Inscriptiones Prov. Raetiae (Munich, 1915).

Illustration Credits

Image 1: Based on Walter Sölter, ed., Das römische Germanien aus der Luft (Bergisch Gladbach: Lübbe, 1981), 43 with additions.

Image 2.1: Based on Thomas Fischer and Konrad Spindler, Das römische Grenzkastell Abusina-Eining, Führer zu archäologischen Denkmälern in Bayern: Niederbayern 1 (Stuttgart: Theiss, 1984), with additions. Graphic: Dr. Gabriele Sorge, Archeological Collection of the Bavarian State, Munich.

Image 2.2: Ground plan from the archives of the Archeological Collection of the Bavarian State; adapted by Dr. Gabriele Sorge.

Image 3: Based on Reinecke, “Eining,” 14, image 14.

Images 4-10: Sketches by Jürgen Blänsdorf; photographs by Stefanie Friedrich; retouched by Dr. Gabriele Sorge, Archeological Collection of the Bavarian State, Munich.