Research into regional and state-level history in Europe is increasingly looking at topics and periods that have seen European bodies play a role alongside national and regional stakeholders of historically longer standing. Starting in the 1950s, the European Communities acquired extensive competences in agricultural, economic, and structural policy that intersected with the powers of subnational entities including, notably, the German Länder. The Council of Europe became an influential driver of cultural policy, and intergovernmental organizations such as CERN and the European Patent Organisation became more significant in research policy.1

Individual works of history, in particular regional studies, have drawn on the concept of multilevel governance as a descriptive category to characterize the new situation—at times tacitly, by highlighting how the emergence of new stakeholders at various levels created new possibilities for shaping states’ policies,2 and in other instances by invoking the concept directly.3 Historians appear to regard the concept as meaningful to the point of being virtually self-explanatory4 and either refrain from defining it or make reference to contributions from political science, a discipline that has been using the concept of multilevel governance since the mid-1990s.5

In their political science research on European structural policy, Gary Marks and Liesbet Hooghe highlighted the roles of subnational authorities, experts, and pressure groups as participants involved alongside member state governments in making and delivering policy decisions.6 This led them to reappraise the assumption that member states are consistently able to control policy outcomes and conclude, instead, that the influence of actors at the different governance levels varies considerably across and sometimes even within policy areas.7

Although historians were well aware of the influence of domestic politics on foreign policy in the wake of controversial discussions of the supposed “primacy of domestic politics”8 since the late 1960s, considerable time passed without any attempts being made to connect this insight with the role of subnational entities in European politics. In political science, however, researchers have embraced the concept of multilevel governance—especially in the context of examining the role the regions played following the Maastricht treaty and how regional and local authorities delivered structural policy on the ground.9

Applied more broadly, however, the insights of this approach can also prove helpful for analyzing pre-Maastricht European integration. Guido Thiemeyer recently pointed this out in his description of the emergence of the European multilevel governance system from the 1950s to the 1980s as a process of “trial and error” involving bodies at the European, national, and state or regional levels that was substantially characterized by unofficial structures and had “no legal basis.”10 Burkhardt-Reich and Hrbek/Wessels used the term “multilevel system” as early as the beginning of the 1980s—and not without reason—“to account adequately for the complex structures and processes in the Community,”11 even as political scientists at the time were otherwise still largely cleaving to a two-level approach based on the assumption that national governments were fundamentally “gatekeepers between the domestic and international levels.”12

Including these perspectives from political science undoubtedly opens up new horizons for the discipline of history as a whole and especially for regional studies.

Fundamental aspects of the multilevel system

Multilevel governance systems arise when “power or competences are distributed between territorially delimited organizations” but “political processes” simultaneously “encompass more than one level” because “tasks are interdependent.”13

Interdependent tasks sometimes crop up because—in an increasingly “denationalized” world—the spaces in which problems arise tend to diverge from the spaces within which individual nation-states have the sovereign authority to bring their problem-solving expertise to bear on them.14 International financial crises or environmental problems, for instance, demand solutions that do not stop at national borders.

Interdependencies also arise—especially in the political system of the EC/EU—because of the ways in which competences are distributed between multiple actors at multiple levels. These range from agenda-setting (e.g., the European Commission has a right of initiative to propose new legislation, often based on proposals from experts) and negotiating decisions (the Council of Ministers with national government representatives who need each state’s respective backing for their decisions, to a greater or lesser extent depending on the country; since 1992 especially and increasingly the European Parliament) to the actual implementation of new policies (national and subnational authorities such as federal states, regions, and local authorities, often in cooperation with non-governmental actors).15

The ability of each level to autonomously exert control is thus limited, necessitating coordination and management across various levels. German federalism research has a word for this: Fritz W. Scharpf’s coinage of Politikverflechtung,16 literally “interwoven politics” but translatable in a number of ways, for example as a framework for joint decision-making or even a joint decision trap. But the same essential mechanisms are also found in unitary states with their voluntary or imposed cooperative relationships between government agencies at different territorial levels.17

The terms “systems of multilevel governance” and “multilevel systems” are common in scholarship within the field. Germanophone research makes especially extensive use of the “multilevel system” (Mehrebenensystem) concept. Conceiving of multilevel governance in this way may appear to evoke a hierarchical system with a “top” and a “bottom,” but neither element is essential. This is especially clear in the case of federally organized states: in Germany, for instance, the Länder (as partially sovereign constituent states) retain a distinct “statehood that is not derived from the federation but is, at the same time, limited.”18 The federation and the constituent states “are not principally superior or subordinate to each other” but are “within their sphere of action … fundamentally independent of one another, albeit bound to mutual loyalty (and under certain circumstances also obedience).”19

Even in regionalized or decentralized states in which the subnational units have only limited self-government rights or have been conceived of as decentralized administrative units, chains of hierarchical command do not work automatically: despite the presence of formal hierarchical structures, the “lower” levels typically are “powerful enough to evade the ‘reach’ of the central level” and can use the threat of non-cooperation to open up coordination channels to the “top”—informally if not officially.20

Using the term “system” possibly promotes a tendency to think in terms of hierarchies and may imply the existence of regularized mechanisms for achieving the necessary cooperation. Such formal relationships are, in fact, given in some cases, for instance when a second parliamentary chamber secures the participation of the subnational level in the formation of national policy or when institutions like mediation committees or constitutional courts resolve conflicts between levels.21 In addition, however, cooperation can take countless informal routes that are mostly not constitutionally defined or capable of generating legally enforceable agreements. The term “multilevel governance”—frequently encountered in Anglophone research— captures the fluid nature of many such cooperative relationships more clearly.

The concept of governance was originally applied to international relations in an effort to clarify that the relationship between states is not organized hierarchically and that satisfactory outcomes can, as a rule, only be achieved through a range of negotiation processes conducted between sovereign states. This was the usage context invoked by Ursula Lehmkuhl with her suggestion that the concept could also provide a productive analytical perspective for historical scholarship.22 Since then, however, the concept of governance has shifted to encompass policy production in its entirety and not only international relations.

“Governance” represents a “counterpoint to ‘government’—understood as control of society exercised in an étatist and hierarchical way”23—and this promotes a shift in perspective that leads away from envisaging “the state as a monolithic subject that is sovereign in its dealings with the outside world and hierarchical in its internal workings.”24

Instead, “governance” foregrounds the substantial autonomy enjoyed by various subdomains in society in modern constitutional states, the large influence non-state pressure groups exert on politicians and policy-making, and the obsolescence of the idea that authority can be exerted smoothly from the top down along hierarchical chains of command.25

At the same time, the governance approach also seeks to avoid the danger inherent to “forgetting, or at least trivializing, multiple phenomena that are empirically evident and involve state control of societal processes in hierarchical form.” It therefore conceives of the hierarchical organization of political processes as only “one of several patterns of managing interdependence between states and between state and societal actors.”26

One of the other control mechanisms27 (apart from hierarchy) is negotiation. It comes into play when a cooperation partner cannot be compelled to take a certain course of action, but interdependence makes reaching a joint solution desirable. Direct communication between the parties creates opportunities for barter, brokering compromise, or seeking concessions, although each party can also break off talks at any point and block progress towards a solution.28

The Association of Alpine States (Arge Alp, short for Arbeitsgemeinschaft Alpenländer) supplies an example case for horizontal negotiations in the European multilevel system. It was founded in 1972. Participating states, cantons, and regions sought to reach joint positions on spatial planning issues and on environmental, cultural, and transport policy that they could advocate vis-à-vis their national governments and at the European level. The desire to cooperate arose out of the conviction of those involved that problems in these policy fields do not stop at national borders and often affect the Alpine region as a whole.

Despite this insight, the partners chose to work in an organization with only minimal institutional structuring that afforded opportunities for coordinated discussion of matters, but allowed for decisions to be reached only when it was possible to do so unanimously—and even these took the form of jointly formulated recommendations addressed to the relevant agencies of the national governments in each country.29

Negotiations between subnational actors can also take place vertically between actors at different hierarchical levels, as the Kramer/Heubl talks on the composition of German delegations to European committees demonstrate. The nub of the problem was that committees had come into existence at the European level in which the German Länder wanted to be represented because the matters addressed fell within the scope of responsibility of the Länder in Germany. In some cases, the relevant committees played merely coordinating roles (this was, for instance, true for the Advisory Committee on Vocational Training). In others, they had substantive decision-making powers (examples included the Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development and the Committee on Regional Policy).

This desire on the part of the Länder clashed with the federal government’s insistence on its primacy in the realm of foreign policy, although the federal government also conceded that the expertise of the state administrations in certain areas was helpful. Resolving the dispute via the Federal Constitutional Court was not an option, as the political cost of losing was too high for both sides. Instead, after protracted talks, the federal government and the states arrived at a negotiated arrangement facilitating the involvement of Länder representatives on a case-by-case basis. Both sides could live with this arrangement, and neither side had to formally cede an inch of its respective legal position.30

The outcome produced by the Kramer/Heubl talks remained a loose agreement, however, essentially “a declaration of intent made by both sides with each side hoping that the other side would respect it.”31 Its interpretation repeatedly proved controversial, but the negotiations had nevertheless produced a passable outcome of sorts, albeit never codified in legislation or used to refine the constitutional order.

Networks are another steering mechanism in the governance concept. They are “more or less institutionalized, stable communication and action systems of connections [between autonomous actors] with an interest in sets of shared development issues and problems.”32 By fostering mutual trust and establishing routine processes of negotiation and decision-making, regular communication between actors in networks may reduce or even avert potential for conflict at an early stage in decision-making. While such networks often emerge between specialist administrative agencies at different levels that are concerned with the same specific policy fields, network links can also develop that connect such specialist agencies with external experts.

The emergence of the EEC mountain and hill farming program in 1974 is a case in point. Right from the beginning of the common EEC agricultural policy, both the Bavarian Farmers’ Association and the Bavarian state government had been opposed to the agenda advocated by agriculture commissioner Sicco Mansholt that favored rapid structural change and a shift to larger and more efficient farms.33 The alternative “Bavarian Way” envisaged the continued coexistence of full-time, part-time, and sideline farmers and aspired to preserve small-scale agriculture as practiced in the Bavarian Alps with state support.

The state government repeatedly appealed to the European Commission to consider agricultural structural policy in a regionally differentiated way, but it was probably the work of agricultural economist Paul Rintelen that was ultimately decisive for the Commission’s decision to recognize, for the first time, the existence of areas or forms of farming for which specific supports could be justified (and to put these supports in place in the form of the EEC hill farming program). Rintelen, a professor at the agricultural faculty of the Technical University of Munich in Weihenstephan, had close ties to Bavarian farming networks and had supervised the doctoral thesis of Bavarian agriculture minister Hans Eisenmann.

After the European Commission tasked Rintelen with conducting a study on the situation of agriculture in the Alpine region, he made a convincing case for the Bavarian view, presented as an important expert opinion in January 1973 that paved the way for the hill farming program.34

This roundabout route taken via the Bavarian agriculture network made it possible to influence the European decision-making process much more heavily than could have been achieved solely through formal channels like the state government lobbying the Bundesrat to reach a position statement that the federal government could in turn have put forward and defended against resistance in the Council of Ministers of Agriculture of the European Communities.

Finally, the governance concept also views the markets and market competition as a steering mechanism: this purely decentral process can cause stakeholders to compare their own performance or successes with the results attained by competitors and to modify their actions in turn.35

Within Germany, the principle of competition between states was evident, for example, in the efforts of Social Democrat and Christian Democrat state governments in the 1960s and 1970s to garner support by demonstrating the superiority of their respective education policies to voters. It also featured in the era of prime minister Edmund Stoiber in Bavaria around the turn of the millennium and the comparisons made then between Bavaria and other German states and European regions that were used by the Bavarian government to justify various policy initiatives.36

Although the concept of multilevel governance emerged from political science analysis of EC/EU regional policy and the regions’ role as formalized in the Maastricht treaty in 1992, much political science literature draws on it to reappraise the relationships between the European and nation-state levels.37 To minimize analytical complexity, authors tend to confine themselves to these two levels.38 Often only a “junior partner” role remains for subnational authorities at the regional level,39 but the fundamental nature of the model of multilevel governance does not automatically predestine them to be sidelined in this way.

Contemporary regional history can shed some light on this blind spot and contribute to incorporating subnational levels into investigations of the European multilevel system.

The emergence of European multilevel governance—A look at the regions

The fact that the European multilevel system extends beyond the European and national levels is attributable, first and foremost, to the very fact that subnational entities exist in member states.

They are, however, by no means a homogeneous group: the number of subnational levels, their nature as legal entities, and their competences depend on whether nation-states are organized federally (as in Germany, Austria and Switzerland), with regionalized structures (as in Italy and Spain), or as decentralized unitary states like France and Norway.40

The characteristic feature of multilevel governance—the organization of government activity by entities with varying territorial scope with interdependencies and coordinated actions—is nevertheless preserved in all of these cases.

The account below will look at the German Länder and the Italian and French regions as examples of states with, respectively, a federal structure, a regionalized structure, and a unitary structure with elements of decentralization. The discussion of these structures is confined here to the period up to the end of the 1980s, since the relationship of the regions to the European level “changed fundamentally”41 after that point. In the wake of European Structural Fund reform in 1988 and the Maastricht treaty in 1992, the nature of the regions as actors on the European stage was utterly transformed. France and Italy also embarked on extensive reform processes in the 1990s that greatly altered the role of the regions in the domestic politics of both countries.42

As a generally accepted definition of the term “region” is still lacking in political science, and interdisciplinary coordination with spatial research remains underdeveloped,43 the following references to regions are made with a degree of caution. The conceptual core of the “region” category can be described as a subspace of medium size, with an intermediary character, that is defined in some way by physical geography and the natural environment, history and culture, political and administrative activity, economic and functional ties, or (as is often the case) some combination of these factors.44

In a prototypical region, these factors would all coincide, but individual regions can deviate from this prototype to varying degrees. One advantage of this approach based on prototype semantics45 is that it allows for the sidestepping of the question whether a region must necessarily have legislative powers of its own to count as such—a characteristic that would exclude Brittany, for instance, although it will become clear below that Breton politicians and the Breton population clearly regard Brittany as a distinct region and represent its concerns as such at the French and European levels.

I. Functional interdependencies and forms of intra-country cooperation

Regionalism in France “as a call for a more rational division of the country and as a counterweight to excessive centralism … has a long and venerable tradition.”46 The French regions emerged in an effort to close the gaping chasm in regional development between “Paris et le désert français”47 that became increasingly evident after 1945. Regional stakeholders spearheaded by the Breton pressure group CELIB (Comité d’étude et de liaison des intérêts bretons) achieved a regionalization of national planning policy in 1956 that saw the establishment of twenty-one “program regions” (régions de programme) for spatial planning purposes (albeit with scant regard for historical and cultural links).48

In 1964, the program regions—now redefined as “circles for regional action” (circonscriptions d’action régionale)—each gained their own Regional Economic Development Commissions (Commission de Développement Économique Régional, CODER).49 The work of DATAR, the Agency for Land Planning and Regional Development (Délégation à l’Aménagement du Territoire et à l’Action Régionale), was coordinated and implemented by the regional prefects. To bring more expertise from the regions on board, the prefects were each assisted by two advisory committees with local elected officials, representatives of the state administration, and members of professional associations.

But the French regions always remained mere technocratic tools geared to improving planification in a modern industrial society. In 1969, President de Gaulle sought to implement his vision of a “participatory society” with a major regional reform that would have turned the regions into territorial authorities with their own councils, budgets, and competences. But this reform effort failed because de Gaulle simultaneously strove to weaken the Senate. By announcing his intention to resign if the reforms were rejected, he effectively turned the referendum on the reforms package into a plebiscite on confidence in his presidency.50

Under de Gaulle’s successor Pompidou, a minor reform in 1972 transformed the regions into legal entities under public law with purely administrative functions in the area of regional economic planning. A regional council composed of national parliamentarians and regional representatives elected from the départements was also created.51

The regions only received the status of territorial authorities—and therefore a legal status equivalent to that of the communes and départements—during the major reform initiative that took place in 1982, during the Mitterrand presidency. Executive power passed from the regional prefect to the president of the—now directly elected—regional council, and the previous comprehensive advance control of all actions (tutelle, as this kind of administrative tutelage by the prefect was called) evolved into a form of retrospective legal supervision.52

The regions acquired competences of their own in the fields of regional spatial planning, infrastructure, and economic development. They also became responsible for providing and maintaining schools of the lycée type, vocational education and training, environmental protection, and regional cultural affairs. But they remained the “economically and politically weaker level” vis-à-vis the départements that were also bolstered in this reform phase, especially as the possibility of one territorial authority exerting tutelle over another was excluded.53

The subnational levels in France do not formally participate in national political decision-making; de jure responsibility for communicating issues of regional concern “up” to the central government rests with the prefects who also simultaneously serve as the representatives of the central state in the départements and regions.54 Although a second chamber that is formally the representative body of all territorial authorities exists in the form of the Senate, the nature of the electoral system means that it is dominated by the small communes and, to a lesser extent, the départements.55

What developed in France in the absence of formal participation structures was a strongly personalized system of interdependences that local elected officials can exploit to bring their interests into the policy process of the central state. This “pouvoir périphérique”56 is founded (apart from the long terms of office of many important local officials) especially on the cumul des mandats (accumulation of offices) at the national and local levels that has been “one of the defining features of French parliamentarianism since the beginnings of the Third Republic.”57

Jacques Chaban-Delmas, for example, not only served as mayor of Bordeaux for almost fifty years, but was also a member of the National Assembly for the same length of time, its president on multiple occasions, a national minister and prime minister, and twice president of the Regional Council of Aquitaine.58 Other top-tier national politicians also held office as presidents of départements or regional councils as a form of symbolic identification with “their” regions and combined “democratic legitimacy with a vestigial remnant of great feudal lordships.”59

Such local notables were able to exert considerable influence in this fashion and to place unsurmountable obstacles in the path of the central state as represented by its prefects in the regions and its control centers in Paris. Formal hierarchical structures thus receded into the background. Conflicts were processed in a tangled web of elected officeholders and state officials with the help of “the cross-regulation system” (régulation croisée)60 that linked “administrative and political sources of authority via personal and territorial ties.”61

In addition to this long tradition of relying on intricate interpersonal connections, subnational units also gained a powerful tool enabling them to co-shape the policy of the national government when decentralization legislation brought in planning contracts. Even before these were put in place, effective spatial planning was not possible without the participation of the subnational levels.62 The seventh national plan (1976–1980) was the first national plan to integrate the regional plans of the newly created regions into the new national plan for France as a whole.

The 1982 decentralization reforms subsequently made the state-region planning contracts (contrats de plan Etat-Région, CPER) “a central tool for managing state investment in cooperation with the decentralized levels.”63 The regions acquired seats on the National Planning Commission (Commission nationale du plan) entrusted with producing a national plan. Once the national plan existed, a negotiation phase followed that led to each region and the state concluding a state-region contract that set out their joint priorities and the level of funding to be awarded.

Although the central government continued to play a strong role and the regions generally had only limited financial resources,64 the planning contracts did establish the “principle of partnership between the central level and the subnational territorial authorities in the sphere of spatial planning and regional policy”65—especially as the financial resources of the regions were often decisive for plugging the last remaining funding gaps that needed to be closed before individual investment projects could proceed.

Foundations were thus laid for the outcomes seen today: a “major result of decentralization policy” can be identified in a shift from “hierarchical, centralist government in which the state (at least formally) had the upper hand” to “negotiation-based settlements.”66

While the French regions were established chiefly to foster functional decentralization, the Republic of Italy was conceived of from the outset—and defined in the Italian Constitution of 1948—as being both “una e indivisibile” and a multilevel system with regions, provinces, and local authorities. It was envisaged that the Italian regions would be autonomous legal entities with powers and tasks of their own.

While regionalization was not uncontroversial, a need to “overcome the excessive centralism of fascism” supplied motivation to drive it forward.67 Even before the constitution entered into effect, the legal prerequisites for regional administrations were created (between 1944 and 1947) in what were to become autonomous regions with special statutes—Sicily, Sardinia, Valle d’Aosta and Trentino-South Tyrol.68

But the Christian Democrats, who initially advocated regionalization, delayed the establishment of the regions envisaged by the constitutional process because they feared left-wing opposition coming from the regions as a threat to their governing majority. Liberals, monarchists, and the ministerial bureaucracy all preferred the unitary model of statehood and were opposed to regionalization.69

Italian regionalization proceeded along doubly asymmetrical lines:70 the content of the special statutes (with the rank of constitutional laws) giving special autonomous status to four regions (later five following the enactment of the special statute for Friuli-Venezia Giulia in 1963) differed from region to region, and the other fifteen ordinary statute regions were different again.

The ordinary statute regions were furnished with considerably weaker competences and budgetary autonomy. In addition, their establishment proved to be a protracted process that dragged on until 1970: although the regions already featured in the constitution, the legislation governing the election of regional councils was not passed until 1968 and the legislation on regional budgets was only passed in 1970. The first regional council elections were held in June 1970 and regional governments were formed. In 1971, the regional statutes were drafted by the regional councils and approved by both chambers of the national parliament. By 1977, the transfer of competences to the regions was finally complete.71

The areas of competence of the regions with ordinary statutes were enumerated in the constitution. Taken together, they depict the regions as an “agrarian economic unit… from the pre-industrial age.”72 Their focus was on markets, local police forces, public welfare, vocational training, local museums and libraries, urban planning, tourism, regional infrastructure including inland waterways, agriculture, forestry, hunting, and, last but not least, the crafts and trades. The regional statutes also generally formulated objectives including participation in regional economic planning and structural policy. Regions with special statutes had additional competences in the areas of culture, industry and the economy, labor law, higher education law, and social security law.73

However, the residual legislative powers remained with the central state, as did numerous obvious and more subtle levers for wielding control over processes. In most cases, only the regions with special statutes had “exclusive power to legislate” while regions with ordinary statutes had to confine themselves to enacting supplementary legislation within the limits of a legislative framework created by the central state. The central state was also able to exert a form of preventive control over regional legislative and administrative activity via government commissioners and supervisory commissions that did not confine itself to regulatory oversight but could also intervene in questions pertaining to the “national interest” or the interests of other regions.74

Taken together with their tightly limited budgetary autonomy, the effect was that the ordinary administrative regions, especially, were strongly dependent on the central state from their very establishment. Only in the regions with special statutes did most of the national taxes levied in each region flow into the budgets of the regional governments.75

While the regions were “kept on the leash of the central state” right from the start,76 the second phase of the transfer of competences from the central state to the regions, which took place between 1975 and 1977, softened the rigidity of the constitutionally envisaged separation of competences and tasks. Especially in administrative action, “diverse coordination and cooperation mechanisms” emerged and responsibility for a given issue “being assigned to only a single level of government became very much the exception rather than the rule.”77 Over time, a system of “unofficial or semi-official negotiations and consultations that was beyond democratic control developed for coordination purposes between the levels and entities involved.”78

This was especially relevant for spatial planning and economic development, areas in which the regions received new competences. The regional presidents were members of both the Interministerial Committee for Economic Planning (Commissione interministeriale per la programmazione economica) and the Interregional Commission (Commissione interregionale), newly created in 1970. Both bodies played a decisive role in planning the national economic program and regional development programs.79

In contrast to the provinces and local authorities, the Italian regions were involved to a limited extent as subnational bodies in the decision-making process of the central government: The regions received a right to propose national legislation, and also a right to initiate national referenda when requests were made by five regional councils. The regions participate in the constitutional bodies of the central state only via the role of regional delegates in electing the Italian president. The regional presidents of special-statute regions were also eligible to participate in cabinet meetings in an advisory capacity during discussions of matters affecting their specific regions. Although the Senate is formally “elected on a regional basis,” it is not otherwise designed as a form of regional representation.80

The State–Regions Conference established at the insistence of the regions in 1983 was initially an infrequently convened body of no great significance, but a 1988 reform transformed it into a standing body chaired by the prime minister, who was required to convene it at least twice a year. It gradually became more significant but remained a purely advisory body “intended, on the one hand, to avoid the exclusion of the regions from the national political scene, but also, on the other, to prevent an effective regional chamber expanding regional representation at the national level.”81

While the French regions are territorial entities with autonomous administrative competences and the Italian regions have legislative competences of their own only to the degree to which the central state has ceded these competences to the regions, the German Länder are qualitatively rather different:

As partially sovereign constituent states with their own constitutions, the Länder possess the quality of statehood and original legislative powers, chiefly in the areas of culture, education, research, internal security, state planning, and administration. They also have the residual competence to legislate in all areas not expressly defined as matters falling under exclusive federal legislative power in the German Basic Law and in areas in which the federal government has not made use of its concurrent legislative competence. The state governments are also participants in federal legislative and administrative processes via the Bundesrat and can, depending on the issue being legislated, exercise an absolute or suspensory veto over Bundestag positions there.82

Reconstruction of the German economy after the Second World War, the importance attached to establishing equal living conditions throughout the federal territory in the Basic Law, and the beginnings of “planning euphoria” combined—especially from the 1960s onwards—to create a steadily more unitarian trend in federal German policy which the Länder were largely unable to counter.

The budget reform of 196983 solidified a model of “cooperative federalism” with its introduction of three areas of joint responsibility (regional policy, agricultural structural policy, and university construction), a uniform fiscal system, greater fiscal equalization between states, and elements of whole-country planning. A large number of joint committees were instituted to address these joint responsibilities of the Federation and the Länder.

While the German Länder and the Italian and French regions are all very different from a constitutional law perspective, striking similarities are evident from other perspectives: the subnational levels in all three states have tasks in the areas of spatial planning, regional structural policy, and infrastructure policy. In Germany and Italy, tasks in the area of agriculture also feature. Hope that the potential of the regions could be made fertile for economic modernization processes was not the least motive behind the transfer of these areas of competence from nation-states to regions.84

But these are areas in which a need for cooperation is especially likely to arise between central governments (that usually, at the very least, have control over funding streams and can thus influence overall planning) and the subnational authorities tasked with delivering policy on the ground. And when competences are distributed, cooperation becomes all the more essential. Even in such a strongly unitary-decentralized system as France before 1982, such cooperation can be observed, as Dörte Rasch clearly demonstrates in her study of French spatial planning policy.85

Once the European Community gained influence in (agricultural) structural policy within the framework of the common agricultural policy, started granting its own investment loans through the European Investment Bank, and was given an expressly designated role in regional policy with the establishment of the European Regional Development Fund in 1975, interdependencies between the regional and European levels became entirely unavoidable.

In Germany, the Länder were involved from the beginning due to their administrative sovereignty. But similar patterns are discernible in Italy and France: the Italian regions were allowed to implement the EEC directives on agricultural reform independently for the first time in 1975, albeit only within the narrow parameters fixed in detailed national legislation passed in advance.86 The reform of the European Structural Funds in the 1980s also led to the Italian regions—in stark contrast to the situation in France—becoming more involved in the planning and implementation of programs.87

In France, the regions were initially only able to influence the distribution of European structural funds indirectly via their planning contracts with the central state. But direct links between French regions and the European Community were forged from 1986 onwards in the context of the Integrated Mediterranean Programmes. The regional council presidents and regional prefects were both program signatories and co-chaired the monitoring committees.88 Although the French central government otherwise retained the power to distribute structural funds for itself alone and granted an active role in the regions only to the prefects, so as not to bolster the budgetary autonomy of the territorial authorities, it did at least involve regional partners in an advisory capacity in program planning and delivery.89

In addition to the ramifications of the structural policy activity initiated at the European level, the regions themselves created additional points of contact between the European and subnational levels with every form of regional economic development they initiated.

The economic policy the member states agreed to in the EEC Treaty was essentially liberal and focused primarily on “fair competition” and the “elimination of restrictions on trade between states.”90 It sought primarily to break down trade barriers and to prevent discrimination against trading partners from other EEC states.91 This liberal economic model found expression in Article 92 of the EEC Treaty, for instance, with its prohibition of state aid except in narrowly defined exceptional cases dependent on Commission approval.

This meant that any regional development policy that the regions in France and Italy or the Länder in Germany wished to pursue always also required that any loans or credit programs involving public funds be approved on the European level. This applied to the development programs for southern Italy administered by the Cassa per il Mezziogiorno and the regions, and it was also true for the Bavarian “zonal border development” (Zonenrandgebiet) programs.92 Several German Länder drew up EEC adaptation plans for their own policies as early as the 1960s.93

II. The self-image of the regions

In political science, the emergence and evolution of multilevel governance is sometimes understood only in terms of the specific interdependencies that arose out of the overlap between the competences of the regions and those of the nation-state and European levels. But the self-image of some specific regions was no less important a factor, as these individual regions advocated for the relevance of the regional level in the European multilevel system and thus ultimately changed the status of regions more generally.

In the German context, the example of Bavaria is particularly salient. With its strong and long-standing tradition of asserting its own statehood, Bavaria (initially with support from North Rhine-Westphalia) was quick to position itself at the forefront of efforts to safeguard the statehood and powers of the Länder in the era of European integration.94

Within Bavaria, the historical dimension was especially foregrounded; the state government was keen to stress, for instance, that the sovereignty of the old Kingdom of Bavaria “lives on in a weakened form in the new Free State of Bavaria”95 and that independent contacts with the European Commission were also “a manifestation of a certain Bavarian self-reliance.”96

The minister president of North Rhine-Westphalia, Karl Arnold, took a different tack with his expression of fears that European integration could lead to a “progressive mediatization of the Länder by the federal government and their transformation into pure administrative districts” because the—intrinsically desirable—vision of a federal European state did not include room for political decision-making at the Länder level.97 States such as Bavaria and North Rhine-Westphalia chose to participate actively in European policy-making to counteract such threats and protect their statehood.

As partly sovereign constituent states, the German states were able to build on their strong position in constitutional law that gave them both original state powers and rights to participate in federal policy-making. But such consciousness of their own statehood and a desire to influence European-level politics was not equally pronounced throughout Germany.

In Italy, too, there were great differences in how involved individual regions became in foreign and European policy. The northern regions of Lombardy, Piedmont, Tuscany, Emilia-Romagna, South Tyrol, and Trentino were especially prominent—the same regions that demonstrate a strong sense of their own distinctive identities in inner-Italian discourse.98 The southern regions seemed disinclined to exert influence on higher-level policy formation and focused their attention more narrowly on the areas of regional autonomy mapped out by the constitution.

The French regions were different again: they had been created solely to meet the needs of regionalized planification. As territorial authorities with purely administrative self-government rights regulated only by ordinary legislation, they encompassed areas that were only historically and culturally coherent to a limited extent. Historically, only Corsica, Brittany, Alsace, and Nord-pas-de-Calais had enjoyed a sense of regional awareness.99 And it was indeed mainly the Bretons, and to a lesser extent the Alsatians, who demanded places for their respective regions in the political fabric of the European Communities.100

The regions mentioned here pursued their objective of asserting the political relevance of the regions in Europe in three ways: by nudging political discourse in the direction of a “Europe of the regions,” by seeking to participate in decision-making at the European level, and by cooperating with other European regions over shared interests or challenges.

<34 id=”iii.-european-discourses-on-regionalism”>III. European discourses on regionalism

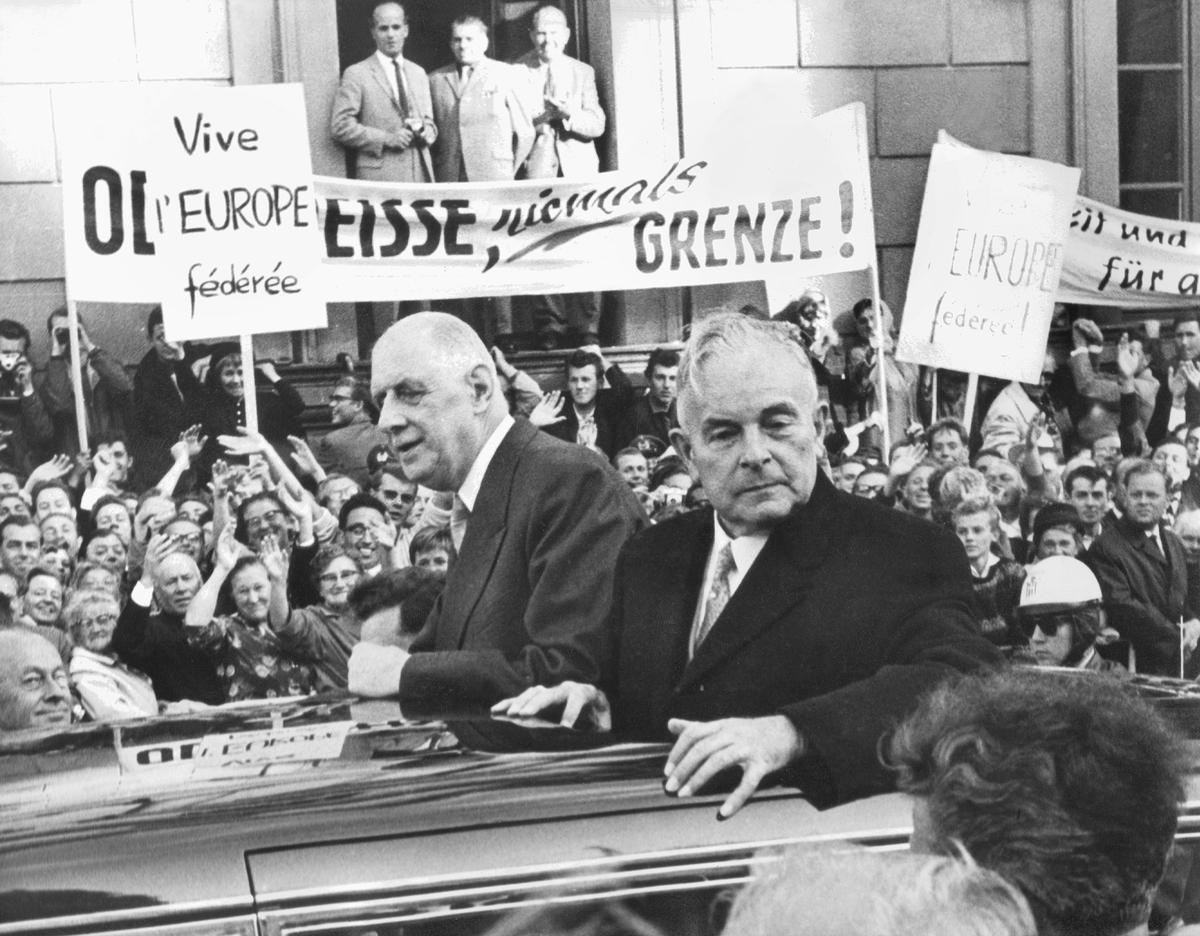

Federalism as the main design principle for a united Europe was a central component of the agenda of pro-European movements right from the outset, but it was often conceived of mainly in connection with the relationship of the European states to a desired European federation.101 The fact that a federal order would also need to include the states and regions at the subnational level was brought into the debate, especially in the Federal Republic of Germany, by politicians from Bavaria and North Rhine-Westphalia.102 Against a background of growing and strengthening regionalism in France, Italy, and the United Kingdom, a Europe-wide debate then began to gain momentum in the 1960s.103

The Swiss philosopher Denis de Rougemont104 coined the term “Europe of the regions” in 1962. He argued that nation-states ought to be abolished because they were simultaneously too big and too small to tackle the problems of the day:105 too small to defend themselves, prosper, and continue to play their former role in world politics, and yet also too big to enable their citizens to personally participate in public life in appropriate and effective ways. Rougemont argued that the larger tasks of the nation-states could be handled at the European level and the smaller tasks could be handed over to the regions.

While French international law expert Guy Héraud106 was pursuing a different agenda with his model of a “Europe of ethnic groups,” he arrived at much the same conclusion about the desirability of abolishing nation-states and favoring smaller regional units. As a scholar of international law, Héraud was primarily interested in the question of how to protect ethnic groups and minorities. He viewed the “(ethnic) nation” as the “natural community” and argued that many nation-states failed to provide this natural community with sufficient protection in cases where it was a minority community. This was the background to his conception of a European federation based on homogeneous ethnic regions that would end the oppression of minorities.107

Both thinkers influenced regionalists in France and the Alpine region,108 and their ideas also diffused into the Sardinian regionalism movement.109 The Council of Europe was likewise highly influential: its committees provided forums that gave regional authorities a voice at the European level and facilitated the development of “une véritable doctrine de la régionalisation.”110

The “Conference of Local Authorities of Europe” became the “Conference of Local and Regional Authorities” in 1975 and the “Committee on Municipal Affairs” set up by the Consultative Assembly of the Council of Europe later became the “Committee on Spatial Planning and Regional Authorities.”111 The European Conferences of Border Regions organized by the Council of Europe in the 1970s contributed significantly to the adoption of the Madrid Convention by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe in 1975. This placed cross-border cooperation between subnational entities on a legitimate legal footing within an international legal framework for the first time. In 1966, the member states had blocked an earlier proposal that would have created such a framework agreement.112

The Council of Europe Conference held in 1978 from January 30 to February 1 in Bordeaux declared itself the “first meeting of the Europe of the regions.”113 By this point, at the very latest, de Rougemont’s concept had been integrated into the self-concept of the regions.

The idea of a “Europe of the Regions” was strongly advocated ahead of the Maastricht treaty in a conference series with that title. This process eventually led to the establishment of the Committee of the Regions and the incorporation of the principle of subsidiarity into the European treaties.114 Even today, “Europe of the regions” is a catchphrase used in contexts extending beyond politics; its recent invocation by Robert Menasse is a case in point.115

IV. Exploring opportunities for political participation

The creation of the Committee of the Regions marked a high point (and one that the regions had long been working towards) in the inclusion of subnational levels in European-level structures. Regions sought to be involved in decision-making processes both because the specific outcomes reached on particular issues affected their interests, given the interdependencies in specific areas outlined above, and because of the wider concerns of the Italian regions and the German states that they could gradually be “dispossessed”116 of their competences by what was perceived as the “regional blindness”117 of the European treaties.

The subnational territorial authorities in Germany and Italy could not participate in the European legislative process even when the issues being legislated fell wholly or partially within the competences they held under domestic arrangements. On the contrary: national governments were now able to influence decisions (via their participation in the Council of Ministers of the European Communities) in spheres for which they were not responsible under domestic arrangements. In Italy, the nation-state also laid claim to the task of implementing European standards even in those areas of policy for which the regions were responsible under domestic arrangements.118

The subnational levels adopted two tactics in their quest for greater influence: they used their clout in domestic decision-making processes to help shape the positions advanced by their respective national governments in the Council of Ministers, and they sought to bypass the national level altogether and influence European institutions directly.

Subnational authorities typically participate in domestic decision-making processes via a second parliamentary chamber. The Senates in Italy and France were, as described above, only suitable for this purpose to a limited degree. In addition, the national governments made it unmistakably clear that how they positioned themselves in the Council of Ministers was an “executive function” and “not at the disposal of any other body,” especially since European policy, as part of foreign policy, fell within the competence of the national executive.119

In the Federal Republic of Germany, the national government was initially only prepared to grant the Bundesrat and the states a weak right to be informed: from the initial EEC negotiations onward, there was an expectation that an observer representing the Länder within the German EC delegation and a Bundesrat special committee would satisfy the states’ need to be kept abreast of developments.120 But this gave the states practically no scope to actively exert influence. Agreement on participation was reached for the first time in 1979, after somewhat acrimonious negotiations, and a procedure for participation was instituted at that point, the Länderbeteiligungsverfahren. After it proved “almost entirely unsuccessful”121 in practice, the Länder pushed for and achieved more far-reaching and legally guaranteed rights during the ratification procedures for the Single European Act and the Maastricht treaty, and Germany’s Basic Law gained a new Article 23 in 1992 that reflected these changes.122

Developments in Italy unfolded in a broadly similar way. When the regions were first established, the parliamentary committee concerned with regional policy unsuccessfully called for the regions to participate in the decision-making process of the central government on matters of concern to the European Communities. Only after a fresh attempt to raise the issue did the regional presidents’ committee gain a weak right to be consulted by the central government in 1975. In this arrangement, the central government still held all the cards: if no consensus was reached, the central government was entitled to make decisions after consulting the parliamentary committee on regional policy.123

At the end of the 1980s, the regions won improvements to their right to be consulted in the context of the State–Regions Conference. The “La Pergola law” enacted in 1989 ensured both that Italy’s European policy had to be discussed regularly in the State–Regions Conference and that regional presidents acquired the right to participate in cabinet meetings discussing European legislation issues of direct relevance to them.124

The regions in France long remained completely cut off from the formulation of the country’s European policy.125 Only the traditional French approach to connecting different political levels, the cumul des mandats and the notables system, allowed certain opportunities to test their influence. One such opportunity arose during the period in which the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) was created: With Jacques Chaban-Delmas, the duc d’Aquitaine, as French prime minister from 1969 to 1972, the two Bretons Olivier Guichard and René Pleven as ministers, and Alsace-born Maurice Schumann126 as the foreign minister, important cabinet members were sensitive to regional policy issues. They placed no major obstacles in the path of the new proposals advanced by the European Commission to institute a common regional policy in the Council of Ministers of the European Communities after previous regional policy initiatives by the Commission had been shelved following resistance from various member states in the late 1960s.127

As the willingness of national governments to allow subnational bodies to participate in the formulation of national policy on Europe remained low in all three member states discussed here, the regions also sought from an early stage to bypass the nation-state entirely and engage with the European level directly.

This could rarely be achieved through formal channels, as there was no official regional representation at the European level. Participation of subnational representatives in national delegations to European Communities bodies remained the exception.128

Efforts to address this gap in representation were undertaken as early as 1950/51 with the founding of the Council of European Municipalities, mainly on the initiative of French and Italian local-level politicians including the mayor of Bordeaux Jacques Chaban-Delmas.129 With this step, the founders took up municipal association models that were familiar to them from their own national contexts and extended them further. The Association des Présidents de Conseils Généraux had, for example, been the most important advocacy group representing French local authorities since 1946.130

The role of unofficial channels for fostering direct contact was considerably more important. In Germany, the Bavarian Minister of State for Federal Affairs, Franz Heubl, spun a web of close ties linking the Bavarian state to the European Commission. Bavarian politicians used “informative visits”—in both directions—to draw attention to specific Bavarian needs in areas like agricultural and structural policy among those responsible for these areas at the European level.131 Especially early on, when the federal government was still trying to prevent contacts, Franz Heubl benefited from his close personal relationship with Walter Hallstein, the first president of the European Commission.132

To a lesser degree, North Rhine-Westphalia also had direct contacts with Europe in the 1950s, and Hamburg, too, made its mark with its own distinctive foreign policy.133 A similar strategy has been documented for Italian regions, albeit not yet to the same extent. In 1975, the regional government of Sicily invited George Thomson, the European commissioner with responsibility for regional policy, to visit that region, but this was an invitation extended jointly with the national government. In 1976, delegations from Emilia-Romagna and Piedmont traveled to Brussels for the first time and met with representatives of the Commission and the Parliament there.134

In the Federal Republic of Germany, a special situation existed insofar as the CSU, a political party active only within Bavaria and politically dominant there, supported the German government coalition for long periods as part of the CDU/CSU Christian Democrat alliance while also being present in the European Parliament with its own deputies.

Due to its role in the federal government, the CSU succeeded in ensuring that Hans von der Groeben remained a member of the European Commission for another term in 1966.135 As the party of Hans August Lücker, who chaired the Christian Democrat grouping in the European Parliament from 1969 to 1975, the CSU was even able to play an important role in the establishment of the European People’s Party.136 In France and Italy, by contrast, regional parties (with the sole exception of the South Tyrolean People’s Party, SVP) played only minor roles during the period discussed here.137

In France, as in Germany and Italy, the regions did not allow the national government to hedge them in entirely, although the French government “militantly favored their exclusion”138 and stressed more emphatically than any other national government its exclusive prerogative to represent the country externally. The Breton pressure group CELIB adapted the domestic strategy it had used to lobby the French government to consider the region’s needs more fully in national structural policy and transferred it to the European level.139

As a legally independent association, CELIB was not subject to state supervision and had more leeway to act as it saw fit than the regional administrative agencies. It was able, for instance, to organize a fact-finding tour of Brittany for members of the European Parliament and Commission officials as early as June 1966. In 1974, CELIB representatives met with European Commission president François-Xavier Ortoli and regional policy commissioner George Thomson and achieved the establishment of an advisory body at the Commission with representatives from European regions and local authorities.140

Although the French national government explicitly banned direct contacts between subnational and European institutions in 1983, CELIB succeeded in being included in the European Commission’s OID program (”Opérations intégrées de développement”) in 1985 in spite of opposition from DATAR, the national spatial planning agency. The Breton network managed to present its outline program directly to the Commission, circumventing national bodies, during a brief window of opportunity characterized by both a phase of experimentation in EC structural policy and a positive buzz around decentralization in France.141

However, the regional office Brittany maintained in Brussels from the late 1980s onwards was largely ineffective because it was under-resourced and hampered by resistance from the central government.142 The constituent states of the Federal Republic of Germany also started opening their own representations in Brussels around this time, but their work and its effectiveness has not yet been examined in depth. The Italian regions were not allowed to set up representations of their own until 1996, and even then only on a limited scale.143

While Brittany’s direct connections to the European level came about through the CELIB network, Alsace was able to exploit the position of the city of Strasbourg as the seat of both the Council of Europe and the European Parliament. Representatives of the city and the Département Bas-Rhin invoked Strasbourg’s vocation européenne when staking their claims to participate in European discourse.

This is particularly evident in the context of the Treaty of Rome: the members of the city and département councils met in the Prefecture of Bas-Rhin on October 19, 1957, unanimously expressed support for “all the efforts undertaken to unite the free peoples of Europe,” and called to “reunite all the European institutions in Strasbourg.”144 This resolution was then dispatched not only to the French Foreign Minister Christian Pineau, but also—with scant regard for official protocol or the division of powers in France—directly to Walter Hallstein, the designated president of the European Commission, and to the chairperson of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe.145

The unofficial Rassemblement Européen referendum on the establishment of a “United States of Europe” presents an even clearer example: fifty-four local authorities in Alsace made their town halls available as polling stations for an unofficial referendum on setting up a “United States of Europe” and the simulated parallel elections to a “Congress of the European People” held on November 24, 1957.146

For decades, the Alsace region also had a personified bridge to European institutions in the form of Pierre Pflimlin. As mayor of Strasbourg for many years and president both of the general council of Bas-Rhin and of the regional economic development commission (CODER), Pflimlin was the leading politician in Alsace. At the same time, through the cumul des mandats, he served not only as a national parliamentarian and minister in France, but also as a member of the Assembly of the Council of Europe and of the European Parliament and even as president of the latter from 1984 to 1987.147

The subnational bodies also sometimes intervened on substantive policy issues at the European level. During the discussion of the Mansholt Plan for the reform of European agriculture, the Italian section of the Council of European Municipalities adopted a position in favor of the plan in May 1969. Nevertheless, the Regional Council of Trentino-South Tyrol, where agriculture was practiced on a small scale and the Mansholt Plan was seen as a threat to traditional structures, simultaneously adopted a resolution clearly rejecting the plan.148

European multilevel governance also found its early expression in Italy and France in similar episodes and phenomena. It can be registered that the regions worked to “‘upload’ the norms of their own member states”149—in other words, that they reached for models already known from the domestic context and sought to apply them to their efforts to shape European institutions and processes: informal contacts through visiting delegations in all regions, somewhat more formal mechanisms of participation in Italy and the Federal Republic of Germany, personal or party networks in Germany and France, and lobbying by umbrella organizations and pressure groups in France and Italy.

V. Visibility through cooperation

The regions contributed to the emergence of a European multilevel system not only by seeking to participate in decision-making processes at the European level but also by working together with other regions that faced similar challenges or had similar interests and finding ways to represent such shared interests collectively. Municipalities along the border between the Netherlands and the German Länder North Rhine-Westphalia and Lower Saxony banded together as early as 1958 to form the Euregio association.150 The Association of European Border Regions emerged out of similar efforts in 1971.151

In 1971/72, a Bavarian and Tyrolean initiative led to the foundation of the Association of Alpine States (Arge Alp, short for “Arbeitsgemeinschaft Alpenländer”), a loose cooperation initially between the heads of government in the states, regions, and autonomous provinces of Bavaria, Graubünden, Lombardy, Salzburg, Tyrol, Vorarlberg, and Bolzano-South Tyrol. The regions aimed to jointly address issues in the areas of infrastructure, spatial planning, agriculture, environmental protection, and culture that did not stop at national borders but were relevant for the Alpine region as a whole.

The heads of the regional governments worked to reach joint resolutions in this loosely structured working group without involving the committees in their respective regional assemblies. They then communicated these results as recommendations to the respective national agencies and also, for informational purposes, to European institutions.

Arge Alp consciously envisaged itself as an “experimental European regional model” and anticipated that such regional working groups across the entire Alpine arch could become the nuclei of a “Europe of the regions.”152 Other working groups did indeed follow: the Alps-Adriatic Working Community in 1978, the Working Community of the Western Alps (COTRAO) linking French, Italian, and Swiss regions in 1982, the Working Community of the Pyrenees (CTP) with regions from France, Spain, and Andorra in 1983, and the Working Community of the Jura (CTJ) with French and Swiss regions in 1985.153

With conspicuously similar timing to the founding of Arge Alp, CELIB convened a Conference of Peripheral Maritime Regions of Europe (CPMR) in 1973. Representatives of twenty-three regions from nine states, ranging from Scotland to Sicily, came together to represent their interests vis-à-vis European institutions jointly.154

The conference had a “caractère semi-privé” but was “sous le patronage” of French spatial planning minister Olivier Guichard.155 The support of this top Breton politician did not suffice to deter the Minister of the Interior from instructing the regional prefects to ensure that the conference was on no account funded from the budgets of participating regions. Jacques Chaban-Delmas stepped in with funds from the city of Bordeaux and the Italian region of Sardinia contributed, as well, and the tide turned when the French government changed in 1977, and the new Minister of the Interior was the Breton Christian Bonnet, who promptly lifted the ban.156

Regional organizations like Arge Alp, the CPMR, and the numerous Euregios were brought together by, as it were, “natural” interests they shared due to a common border area or a similar (peripheral) geographical location.157 Other bilateral or multilateral alliances were created to institute formal links between regions that were not neighbors but nevertheless wished to cooperate more closely. A partnership agreement building on earlier bilateral ties was, for instance, concluded in 1988 between the German state of Baden-Württemberg, the Spanish autonomous community of Catalonia, the Italian region of Lombardy, and the French region of Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes. As the “Four Motors for Europe,” these regions aimed to cooperate especially in the areas of business, technology, and research.158 The idea was not to create a new spatial unit, but to advocate for shared socioeconomic interests at the European level and exploit synergies between the regions.159

As these various kinds of cooperation between regions progressed, a Europeanization of the regions was simultaneously taking place: as countries and regions engaged in political exchanges, developed joint strategies, and competed for the best solutions, they began to site themselves in broader comparative political and economic frameworks. While regions had always had their immediate neighbors in their own nation-states as jumping-off points for comparisons, other European regions facing similar challenges now started coming into view as possible points of reference:

One concern of the European Wine Regions Conference (CERV) founded in 1988 at the instigation of Edgar Faure, Jacques Chaban-Delmas, and the Council of Europe director Gérard Baloup was jointly representing the interests of wine regions to the European Commission, which was responsible for regulating the wine market in the context of the common agricultural policy. But the increase in political cooperation between the regions inevitably also led to individual regions becoming more aware of their own market position and their own special interests. At times, competitive wrangling for the best solutions also came into play (in the working group on training winegrowers, for example).160

The interregional cooperation that broke new ground and spawned a growing number of organizations in the 1970s was a significant component in European regions becoming increasingly vocal and visible in the 1980s and thereby gaining greater political heft.161 In France and Italy, especially, the rise of regional units gave rise to a new and increasingly self-confident “première génération d’exécutifs régionaux.”162 Joint umbrella organizations such as the Liaison Office of European Regional Organisations (BLORE) developed into important pressure groups linking the regional and European levels; BLORE was founded in 1979 and evolved into the newly established Council of European Regions in 1985 that was known as the Assembly of European Regions from 1987 onward.163

VI. The openness of European institutions

In addition to the regions being interested in participating at the European level, the European institutions also had motives of their own for fostering their ties with the regions.

The European Commission organized a Conference on Regional Economies as early as 1961 that left some participants unable to “avoid gaining the impression that regionalism was being encouraged here by the Commission.”164 In its proposal for the First Medium-Term Economic Policy Programme, the Commission expressly envisaged consultation with the regions affected by regional policy measures. The member states unequivocally rejected this proposal in 1966, however, and stressed that they and they alone were the Commission’s dialogue partners as defined in the treaties.165

The Commission nevertheless continued to purposefully pursue the establishment of a European regional policy166 and to maintain contacts with subnational territorial authorities. Regional Policy Commissioner Albert Borschette justified this in a lecture given in Munich as follows: “To fulfill its political mandate, the Commission not only needs constant dialogue with the governments of the member states. It also needs direct contact with the governments of the Länder and the authorities in the regions.”167 Formal justification for this logic was available in the form of Article 213 of the Treaty of Rome, which stipulated that the Commission could “collect any information and carry out any checks required for the performance of the tasks entrusted to it.”

The Commission’s self-image as a motor driving European integration and seeking to promote progressive unification at all levels was probably a contributory factor in this policy. What was just as significant, however, was that having open lines of communication with the regions improved the Commission’s negotiating position vis-à-vis the Council, in which decisions were made by representatives of member state governments, since the Commission was able to draw on informed insights into the progress of domestic discussions and into possible differences of opinion at the domestic level to poke holes in monolithic arguments put forward by member states. The German Federal Ministry of Economics indignantly registered as early as 1964 that the Länder were “tripping up” of the federal government when the Commission raised repeated objections based on information it could only have gained from Länder sources.168

European regions encountered especially fair winds in the 1970s. While Walter Hallstein, the Commission’s first president, had already sought contact with the regions, an entire series of people well-disposed towards the regions held posts in the Commission during this decade of supposed “eurosclerosis”: Industrial Affairs Commissioner Altiero Spinelli was a passionate federalist. Regional commissioner George Thomson, a Scot, recommended that his homeland take its cue from Bavaria and establish its own contacts with Brussels.169 In 1974, Thomson and Commission president François-Xavier Ortoli—himself a Corsican!—met with CELIB representatives and agreed to set up an advisory body at the Commission with representatives from European regions and local authorities.170

The Bavarian commissioner Peter M. Schmidhuber also gave decisive support to the regions-friendly establishment of a Consultative Council of Regional and Local Authorities in 1988, the predecessor of the European Committee of the Regions (CoR). This was a body for which the Council of European Municipalities and Regions (CEMR) had long been campaigning.171

While the European Commission sought to give the regions access to the European level through regional policy as a policy field in which it had gained increasing competences, the Council of Europe granted the regions their own place in its structures. Since the 1950s, the Council of Europe had been attempting to involve local and regional authorities in its work and to provide them with a political forum so that European unification could grow from below as well as being fostered by national governments.172

At the urging of the Council of European Municipalities, the Consultative Assembly of the Council of Europe set up its own municipal affairs committee as early as 1952. In 1955, it decided to convene an annual conference of local authorities. This European Conference of Local Authorities met for the first time in 1957 and was officially set up by the Committee of Ministers in 1961 as an advisory body tasked with advising the Council of Europe on municipal issues and keeping European municipalities abreast of European issues.173

In 1965, the Council of Europe politicians Fernand Dehousse, Nicola Signorello, and Willi Birkelbach took this initiative further again with their call for a European Senate with regional and national representatives to be established within the EEC to foster democratized European regional policy.174 Until then, the European Conference of Local Authorities had also dealt with the problems of peripheral, disadvantaged, or border regions as a kind of proxy.175 But in 1975, the formal remit of the Conference of Local Authorities was expanded (at its own request) by the Committee of Ministers to include representation of the regions; by this point, the Council of Europe conferences on European peripheral and border regions (Brest 1970, Strasbourg 1972, Innsbruck and Galway 1975) had left an impression.

The establishment of the new Conference of Local and Regional Authorities of Europe sought to give a voice to the regions and to promote closer ties between the Council of Europe and the European Communities.176 This represented a “milestone in the development of international law, and specifically European law, as it gave regions within states a firm place—however modest—in European-level institutions for the first time.”177

The nation-states (or rather their governments) dragged their feet and obstructed all these developments. They were reluctant to cede or unnecessarily weaken their position as gatekeepers between European and national politics. From their point of view, organizing negotiations with Europe as a “two-level game”178 where they faced the Commission alone in the Council of Ministers was a logical goal. Attempts by national governments to prevent subnational bodies from engaging in contacts with European institutions are known from all member states.

In Germany, preventing Bavarian delegations from making regular informational visits to Brussels proved impossible. In Italy, the prohibition of official contacts between the regions and the European level (a ban that also encompassed informal contacts until 1980) was “undoubtedly among the least heeded” rules179—just as the promise extracted from the European Commission by the French government in 1993 that the Commission would respect the internal distribution of powers in France and refrain from fostering regional autonomy also scarcely had practical consequences.180

But for all their resistance, it was often the nation-states themselves that made decisions that—often unintentionally—advanced the development of a European multilevel system. By creating the regions and furnishing them with certain competences that were at least partially encroached on by European competences, the French and Italian governments created a degree of interdependence with the European level that made mutual contact inevitable. At the European level, too, the nation-states made decisions that strengthened the hand of the regions. At a 1972 Paris summit, the long-standing efforts of the Commission to finally establish European regional policy as a distinct policy area in its own right finally paid off when government leaders recognized that regional policy was necessary for a stronger Community and decided that a European regional development fund could be established.

While the reasons underlying this decision were mainly political and tactical—the idea was to smooth the path of the United Kingdom to becoming a member state181—the momentum it created was unstoppable and the nation-states soon had to live with the consequences: once the Commission had powers of its own in the area of regional policy and funding to disburse, the European and subnational levels automatically moved closer together because they had more common ground on substantive policy issues.

In the Council of Europe, too, the Consultative Assembly initially pushed to have local and regional bodies more involved in the Council’s mandate and then decided to establish a Municipal Committee and convene the Conference of Local Authorities of Europe. The Conference formulated “une véritable doctrine de la régionalisation” on its own initiative182 but its formal recognition as a consultative body of the Council of Europe was effected by the representatives of national governments in the Committee of Ministers in 1961. The Council’s mandate was subsequently extended to encompass the representation of the regions in 1975.183 The Committee of Ministers also decided to establish a European convention on cross-border cooperation between territorial authorities in 1975—after avoiding a decision for the best part of a decade.184 While the nation-states made numerous protocol declarations geared to undermining the effectiveness of the new convention, an international law framework giving legitimacy to cooperation across borders between subnational units now existed and went on to develop dynamics of its own that were beyond the control of nation-states.