Summary

In 2000 the extensive fortified citadel of Bernstorf near Munich in Germany, which burned down in or after c. 1320 BC and had already yielded some gold regalia of rather Aegean appearance, produced two amber objects seemingly inscribed in Linear B. The authenticity of these objects has been questioned, on grounds that are as yet insufficient. A new reading suggests links with a place called *Ti-nwa-to, the existence of which is attested by the Mycenaean archives at Pylos and possibly at Knossos. Women from this place worked at both palatial centers as weavers, but it also had a wealthy ‘governor’. An analysis of the Pylos tablets suggests that this place was in western Arcadia. This material sheds light on long-distance connections in Mycenaean times.

1. The finds from Bernstorf

Some archaeological and epigraphic finds are so startling that they seem to make no sense. With no knowledge of the Vikings, we would not expect to discern Norse runes on a stone lion in the Piraeus or discover Arab dirhams in Dublin. The Aegean script Linear B should not be found in Bavaria, even in a Bronze Age context. Any attempt to explain such a puzzle will of necessity draw on various disciplines and materials – in this case, the epigraphy of Linear B, early metallurgy, records of governors and female slaves at Pylos and Knossos, amber in Messenia, the geography of the kingdom of Pylos, and historical evidence from c. 1350–1200 BC for roving warriors in the Levant and Aegean. Only by adopting a very broad outlook can we hope to explain something so bizarre – unless the objects from Bernstorf are outright forgeries. But what if they are not?

The hamlet of Bernstorf lies in Upper Bavaria near Freising in the vicinity of Kranzberg, on the river Amper not far from the Danube and some 40 km north of Munich. It happens to be the site of the largest Middle Bronze Age fortification so far known north of the Alps. The site was located in 1904 by Josef Wenzl, a local schoolmaster, who drew a sketch-plan of the fortifications, half of them buried in the forest. Since 1955 two thirds of the enceinte has been destroyed for the extraction of gravel and marl; its original length was 1.6 km and it encompassed an area of 12.8 ha. In 1992 two amateur archaeologists associated with the Archaeological Museum in Munich, Manfred Moosauer, an ophthalmologist, and Traudl Bachmaier, a bank-employee, discovered that the site was enclosed by a timber stockade that burned so fiercely that vitrification occurred; the temperature reached was 1350 °C1. With the authorities’ permission, they excavated a small area of its NE sector in 1994–8. Burned timbers yielded a preliminary 14C date for its construction of 1370–1360 BC, during the local late Middle Bronze Age2.

In August 1998, after the archaeological excavations had ended, the contractor’s bulldozers and graders tore up the trees over an area of about 1 ha within the rampart inside the gate. Reportedly, the drivers found a hinged bronze cuirass with nipples rendered in pointillé, a bronze helmet and bronze weapons, all too small to fit modern men3. Moosauer and Bachmaier, in dismay at the devastation, investigated the spoil-heap on 8 August and began to discover among the uprooted tree-stumps an extraordinary hoard of amber and golden objects that had been carefully folded and wrapped in clay; after the first object was unearthed, most of the finds were made under official supervision between then and 29 April 1999, and all were taken promptly to the Museum4. Most of the material was encased in its original clay packing, which has been analysed and proves to come from Bernstorf5. This remarkable cache included six irregular centrally perforated lumps of amber6, a wooden sceptre which partly survived in a carbonized state (at the laboratory in Oxford the charcoal received a calibrated 14C date of 1400–1100 BC with 95.4% probability)7 and had a spiralform gold wrapping8, a gold belt with pierced triangular ends, a gold bracelet, a crown made of two layers of sheet gold with five attached vertical elements rising from its horizontal headband, a dress-pin of twisted gold with a flat triangular head, a gold diadem or cloak-fastener with pierced, pointed ends, and seven square gold pendants pierced at one corner for attachment (Fig. 1); in total these weigh 103.4 g9. The jewellry is made of sheet gold uniformly c. 25 mm in thickness10. Most of it was produced by a single workshop in repoussé by hammering the gold with punches made of bone or wood rather than of metal11; the decoration is rows of concentric circles and of diagonally hatched triangles, with a square tooth-pattern along the edges12. However, pointillé decoration is used on the sceptre and pin-head, which bears the wheel-pattern ? impressed in dots (there is no suggestion that this is writing)13. The projections on the crown were held in place with slots, as in Aegean crowns as early as that from Mochlos Grave VI14. The hoard was at first dated to the 16th or 15th centuries BC, because the style of the goldwork was compared with that of the rich finds from the Shaft Grave Circle A at Mycenae15. However, parallels with the gold of the Shaft Graves are weak16, and an initial 14C calibrated date of the wood from the sceptre, obtained in the laboratory at Oxford, gave a result of 1390–1091 BC17; three further 14C tests have given a tighter chronological range, with two yielding 1389–1216 ± 1 BC18. Although this is the only gold crown possibly of Aegean type that has been found outside the Aegean19, the treasure has been thought to derive from a local workshop under both Carpathian and Mycenaean influence20, or to come from a local workshop using material imported from afar21. The metal is too soft for the objects to have been used in ordinary life, and they were certainly ceremonial equipment; it has plausibly been proposed that they adorned a cult-statue or xoanon22, but they could also have been used for mortuary purposes. Analysis showed that the crown bore traces of styrax-resin, used for incense and native to southern Arabia23. The gold bears some traces of combustion. In its final use it was carefully folded and deposited as a hoard. Further excavations, now led by the Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege, took place on the S. side of the rampart in 1999–2001, and revealed that it had been constructed from an estimated 40,000 oaken logs and was completed with a ditch.

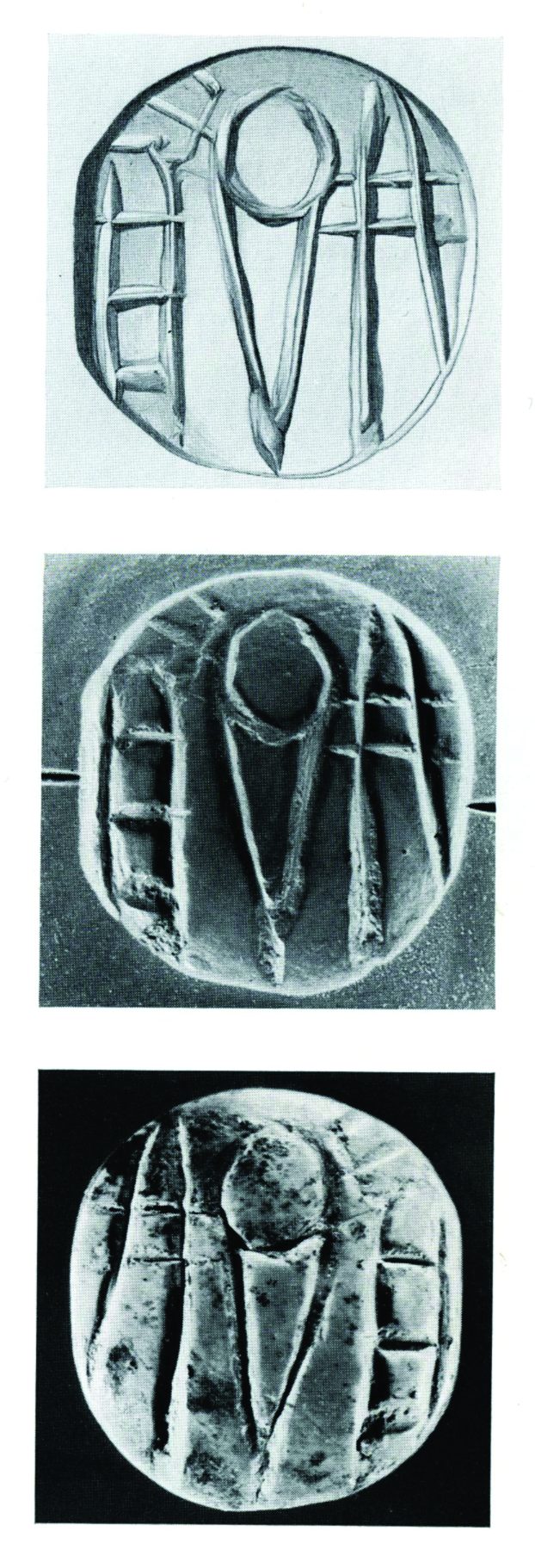

During the archaeological excavations of 2000, the directors decided to use a mechanical digger to clear an area of previously unproductive soil within the rampart, some 50 m E. of the find-spot of the hoard, in preparation for another rescue-excavation; however, after heavy rain, the resultant spoil-heap was seen to contain some prehistoric sherds, whereupon they asked the amateurs to search it. On two successive Saturdays, 11 and 18 November, Moosauer and Bachmaier, together with Alfons Berger, the deputy mayor of Kranzberg, found two inscribed amber objects, Objects A and B, along with sherds of a local Middle Bronze Age pot decorated with incised lines24. These were promptly handed to the Museum, where Object B was found still to be surrounded by a matrix of local sand and clay; they are described below.

Amber Object A (Figs. 2–3) is a roughly triangular piece of dark brown amber, 3.21 cm wide by 3.05 cm high and 1.08 cm in thickness. It has on the ‘obverse’ (Fig. 2) a male face with eyebrows, nose, mouth, and ears shown by simple incised lines; incised circles represent the eyes, and a beard is indicated by a number of short oblique incisions (no moustache is shown). It has been compared the famous gold funeral mask of ‘Agamemnon’ found by Heinrich Schliemann in Shaft Grave V at Mycenae,25 but is actually very crude. The ‘reverse’ (Fig. 3) bears three incised linear signs that in general appearance resemble the Linear B script. However, two of them are in fact very hard to identify in that script (see §7). Like the amber beads in the hoard, its edges and reverse display signs of melting and burning. However, where it is unburnt one can see that the surface of the reverse was smoothed or polished before the incisions were cut.

Amber Object B (Fig. 4) might be held roughly to resemble a scarab in shape. It is made of bright yellow amber. It is 2.1 cm high, with a flat oval obverse measuring 2.4 by 3.1 cm and and a convex reverse. It has a conical hole 0.35–0.31 cm in diameter drilled from one end only along the longer dimension of the reverse. Its upper and lower surfaces were carefully smoothed and polished before the incisions were made. Two thin strips of sheet gold, of much the same thickness and composition as the gold of the treasure, were found by X-ray analysis deep within the hole. The object seems not to have been burnt. On the obverse it bears three incised linear signs. The ‘exergue’ below the signs on its obverse bears a horizontal line with five vertical elements rising from it; this has been interpreted as a reasonably accurate depiction of the gold crown seen in Figure 126. Above this it has three signs, which were correctly read in Linear B as ??? pa-nwa-ti in the editio princeps, where the inscription received the number BE Zg 227. This reading of the signs is opaque in meaning, but the presence of the sign ? nwa confirmed, in the eyes of both the experts who were consulted at the time, L. Godart and J.-P. Olivier, that we are dealing with Linear B rather than Linear A, in which script that sign does not occur28. We shall return to their reactions below (§2).

Further excavations of the south-west sector of the ramparts followed in 2007 and 2010–11, together with a geomagnetic survey by the University of Frankfurt. These have showed that occupation at the site began in c.1600 BC, and that after its abandonment it was reoccupied to a lesser extent in Hallstatt and Medieval times29. Although 14C dating has given two possible chronological ranges for the construction of the rampart, 1376–1326 or 1317–1267 BC30, dendrochronological study shows that its logs were felled between 1339 and 1326 BC, more probably close to 133931. Local archaeologists believe that it was burned within one generation of its construction, since in their view such structures were never long-lived32.

The curators of the Archäologische Staatssammlung at Munich are certain of the authenticity of both the inscribed amber and the golden objects, which, they write, is guaranteed by the find-spot and the circumstances of the discovery, by the investigations that were immediately carried out in their laboratories, and by subsequent research33. Careful scientific studies have produced no valid proof that any of them have been tampered with since their discovery34. However, the purity of the gold is a stumbling-block. The first X-ray fluorescence analyses revealed the gold to be highly refined, with under 0.5% of base metal and under 0.2% of silver, presumably by the use of the salt cementation method that is first described by Agatharchides of Cnidus in the 2nd century BC35; the dearth of silver shows the gold could not be a local product from alluvial sources36. Salt cementation is first documented archaeologically in Sardis in the mid-sixth century BC, but could have existed in the Bronze Age37. Later studies have shown that the gold is about 99.7% pure by weight; none of the pieces contains any copper or silver at all, but traces of antimony, sulphur, mercury and bismuth in proportions that are roughly similar in all the objects38. The two small pieces of gold wire from deep within the perforation of amber Object B39 have a purity and composition almost identical to that of all the other golden objects from Bernstorf40. This shows that the authenticity of both sets of finds is a single question, which is also linked to the early radio-carbon date of the wood from the sceptre. The presence of these trace-elements has been held both to exclude modern electrolytic gold41, and to prove that this is what the Bernstorf objects are made of42. There are still rather few comparanda for the composition of early gold; only a handful of Bronze Age artefacts from Northern Europe are made of such pure gold, notably the Moordorf disk, which also has similar decoration43. However, such gold is known from the handle of a Mycenaean sword from Chamber Tomb 12 (the ‘Cuirass Tomb’) at Dendra in the Argolid; the tomb was closed in LH IIIA 1, but the sword may be LH IIB. This was pure except for 0.01% silver, 0.13% bronze, 0.002% tin, and 0.017% platinum44. The gold matrix of the mask of Tutankhamun is 97–98% pure by weight45. A finger-ring from Amarna is 98.2% pure46, while the gold in the so-called ‘coffin of Akhenaten’ found in the Valley of the Kings (KV 55) is 99% pure47, but differs in other respects48. For paucity of comparative data, we simply do not yet know how pure Bronze Age gold could be49. Lack of comparative data also hinders the determination of the origins of central European and Mycenaean gold50; the latter has been linked with Transylvania, Nubia, or possibly the Black Sea.51

The amber is succinite from the Baltic52. When at the Museum Object B was first removed from the matrix of local sand and clay in which it was found, it looked like new. Freshly cut amber fluoresces strongly under ultra-violet light, and this phenomenon lasts for ten to twenty years of exposure to light and air. When both pieces were examined shortly after they were found they fluoresced very faintly53. However, examination of other pieces of amber found in an excavation at Ilmendorf near Ingolstadt showed that they too all fluoresced faintly, whereas no fluorescence was seen in any of over a hundred pieces of Roman and Bronze Age amber in the Archäologische Staatssammlung which had been out of the ground for between thirty years and a century. Rather than prove these items to be forgeries, the comparison shows that the amber was relatively fresh when it was buried, and that its fluorescence was preserved by its burial54. Like the gold and amber from the cache, the two inscribed objects show traces of burning and melting. The lack of reoccupation at Bernstorf until the Hallstatt period suggests that the destruction of its fortifications provides a terminus ad quem for the artifacts found there. The hoard of gold and the carved amber objects were perhaps buried for safety by their owner or owners, never to be recovered, before the fortifications were fired, or were rescued from the fire and interred shortly thereafter.

2. Reactions to the discoveries

Kristiansen and Larsson, in a wide-ranging study of travel and trade in the European Bronze Age, accept the authenticity of the finds at Bernstorf and regard them as an important support for the thesis that there were extensive contacts in LH II–IIIA (1500–1300 BC) between Scandinavia and the Tumulus Culture of southern Germany on the one hand, via the Adriatic, with the eastern Mediterranean on the other55. As they note, the Uluburun shipwreck of c. 1305 contained both Baltic amber and an Italian sword56, as if amber routes via Central Europe and Italy were still operative57. However, the finds at Bernstorf were too outlandish and remote for them to have attracted much notice from scholars of the Aegean Bronze Age, a field which has seen some notorious forgeries and hoaxes58. Our inability thus far to identify parallels for Linear B on seals, to interpret the inscriptions convincingly, and to account for the nature of these objects has contributed to their continuing obscurity. When they have been noticed, they have attracted profound scepticism59.

Since the discovery of Linear B inscriptions in a Bronze Age context so far from Greece is completely unparalleled, forgery has been alleged, on several grounds: the amber objects were found by amateur archaeologists in an unstratified context, incisions can easily be made in amber, and assessing the condition of amber is a complicated question; convincing ‘antiquities’ made of it are not hard to create, and unworked amber was frequently found at the site60. Moreover, the discovery came at a convenient time to lend publicity to a book about the recent find of the cache of gold from the same site61. But it does not suffice to argue ‘was nicht sein darf, kann es nicht geben’, nor to try to impugn the integrity of their discoverers when there are no grounds for doing so62. Nor is it a valid objection to authenticity that the Bavarian amateurs have sometimes confused Minoan and Mycenaean in their publications63, and have made some far-reaching and probably exaggerated claims about their significance64. It should hardly need saying that wild comparisons and errors in popular publications do not in themselves constitute arguments that the objects under discussion are fakes (compare the Phaestus disc).

The reactions of Godart and Olivier to the inscriptions were mixed.65 Godart regarded the second and third signs on Object A as possibly Linear A, but rejected its overall authenticity. He would not have hesitated to accept the authenticity of Object B had it been found in a Bronze Age Aegean context, and read the signs as pa-nwa-ti. But he concluded that both were forgeries, because Object B was found with Object A, which he considered a forgery, because no amber seals are incised with Aegean scripts and only one seal is inscribed in Linear B (see below), and because they were found in Germany66. Upon learning, from further correspondence, of the previous discovery of the hoard of gold, he wrote that there can be no question of forgery in this case67. Olivier read the signs in Linear B as a symbol probably followed by ka-a on Object A, and as pa-nwa-ti on Object B. He too was astounded by the findspot, but moderated his scepticism after further correspondence.68

Apart from the possibility of forgery, three other reasons have been offered for rejecting the inscriptions from Bernstorf. First, if Object B is a seal its shape is unparalleled in the Minoan and Mycenaean corpora69. Secondly, if the parallels between the golden crown, the frontal portrait of a face on amber Object A, and the treasures from Grave Circle A at Mycenae, including the ‘Mask of Agamemnon’ from Shaft Grave V, are valid, these objects are much too early to be associated with Linear B70, which is first attested in the LM II or early LM IIIA 1 archive from the Room of the Chariot Tablets at Knossos71. Finally, although Linear B signs were freely written over sealings impressed on clay, ‘seals were not vehicles for Linear A and B. Nor was amber used for making them’72. However, these objections can be met.

First, although the shape of Object B (Fig. 4) is certainly unparalleled among Aegean seals, it may have been left largely in its natural shape. Object A largely retains its unworked shape.

Secondly, the gold is definitely to be dated after the Shaft Grave era on grounds of style, and perhaps too because of the purity of its composition. The similar composition of the gold wire found inside Object B seems to prove that the gold treasure and the inscribed amber were used together before their final depositions. Gold and amber were both worked in Room B of the palatial workshop at 14 Oedipus Street at Thebes in Boeotia73. If the goldwork were to be from the Aegean, its style does not match that of Late Middle Helladic and Early Mycenaean gold from the Argolid and Messenia, since both in Greece and in central Europe spiral and curvilinear decoration predominates at that time74. In this case, it was made later, perhaps in a peripheral area.

Thirdly, Linear B was certainly written on materials other than palatial clay tablets and Cretan stirrup-jars for trade in olive-oil. There must have been records on perishable materials, notably longer-term ledgers that correspond to the yearly records kept on the tablets75. The retention for two centuries or more of the curvilinear shapes of the signs, although they are written on clay, is a decisive proof76. Moreover, inscriptions on a sherd and on a stone weight have come to light at Dimini77. There are also a few connections between amber, seals, and Linear B. A single seal made of amber was found at Mycenae, an amygdaloid with grooved back showing a bull78; another probable specimen was found in a tholos-tomb79 at Pellana in Laconia dating to LH IIIA80, and a third in tholos-tomb 1 at Routsi (Myrsinochori) in Messenia (LH IIIA), which may have borne a rare frontal image of a human head81. Their existence shows that amber was sometimes worked after its arrival in Greece82. In addition, there is a Linear B inscription on a seal from a secure Mycenaean context. A lentoid seal now in the Museum at Delphi83, MED Zg 1 (Fig. 5), fully legible as Linear B, was found in the LH IIIC tomb 239 at Medeon in Phocis. Such items in LH IIIC tombs are often ‘heirlooms’, and naturally one suspects that it in fact dates from LH IIIA–B, when Linear B was still used84. It is published as ivory but is probably made of bone85. It has no figural decoration, but only the signs (reading from left to right) ??? e-ko-ja, an unparalleled sign-group86. However, every sign in this inscription happens to be symmetrical about its vertical axis; a retrograde reading of the seal from right to left would give a dextroverse reading in the impression87. If the order of the signs is indeed reversed, they read ??? ja-ko-e88. Both ja and e have medial as well as initial uses in sign-groups, but ??? e-ko-ja is perhaps preferable, since ? e is more common as an initial sign. Unfortunately neither reading supplies the basis for any obvious interpretation, and neither evokes any obvious parallel in our present corpus of Linear B. We are probably dealing with an unknown personal name or conceivably toponym89. The interpretation of short sign-groups in this script is always far harder than that of longer ones, particularly in cases like these where there is no context to help determine the meaning90.

3. A Fresh Approach

As was observed soon after the discovery91, all the signs in the inscription on Object B, ??? pa-nwa-ti (Fig. 4), are symmetrical about their vertical axes, like those on the seal from Medeon (Fig. 5). They are therefore open to being read in either direction, either as a seal or as an impression. Although microscopic examination shows that the lines were engraved from left to right92, and left to right is the invariable direction in Linear B, we should be open to a sinistroverse reading, since the impression of the signs would inevitably be read in the normal direction from left to right. If we do reverse the sequence of signs, we obtain ??? ti-nwa-pa (Fig. 6). This reading is still obscure, but it reminded Olivier of the ethnic adjective ti-nwa-si-jo that is well known in the Pylos tablets93.

I suggest that in fact there has been a mechanical confusion between two signs of similar shape. Experts on Linear B are even more wary than classical scholars of corrections to their texts94, because of the high level of uncertainty that the interpretation of Linear B involves, but this should not absolve them from considering intelligent emendations when ratio et res ipsa demand them; texts written in Linear B are no more exempt from error than those in any other script. As Ilievski showed, errors that depend on the confusion of sign-shapes do occur, and several other kinds of mistake, like the omission of a final syllable, are as verifiably frequent in the corpus95. In this case the intended inscription would have been ??? ti-nwa-to rather than ??? ti-nwa-pa, entailing the easy confusion between ? pa and ? to. Such errors are common in Linear B, and include ? na versus ? to96, ? pa versus ? ro97, and ? pi versus ? ti98, although not so far as I know ? pa versus ? to.

In this case ? to seems to have been changed into ? pa rather than the reverse. Magnification of the high-resolution image (Fig. 6) proves that the upper part of the vertical in ? pa was created as a separate incision,99 which was made in a different movement from the rest of the upright. This mode of writing it was normal among the scribes of Linear B100. Since the uppermost vertical is not crossed by the upper horizontal, which was incised from left to right, we cannot tell on that basis which line was cut first. However, since the uppermost vertical of ? pa projects above the apex of the sign ? ti that occupies the opposite, equivalent position on the oval flan, it breaches the symmetry of the engraving, in which the middle sign ? nwa ought to have projected above the signs on either side. Thus the mistake was probably caused by the engraver, who revised his opinion as to which sign he was meant to write, and altered his original ? to into ? pa101. Perhaps he was not himself literate, unlike the person who had written his exemplar; in Mycenaean Greece, a scribe was by definition literate but we have no evidence that craftsmen were. To the objection that, if the amber was originally a Mycenaean symbol of authority, such an error ought not to have escaped the notice of the ruler who commissioned it, I would reply that not all rulers of early societies were literate; the Mughal king Akbar was not, nor William I of England, to whom his rebellious son Henry I defended his bookish ways by saying ‘rex illiteratus, asinus coronatus’102. This mistaken correction, once made, could not have been reversed without ruining the precious amber. I conclude that the original reading was ti-nwa-to.

The sign-group ti-nwa-to is not directly attested in the Linear B tablets, but the adjectives ti-nwa-si-jo (masculine)103, ti-nwa-si-ja (feminine nominative plural)104 and ti-nwa-ti-ja-o (feminine genitive plural)105 appear in the archive from Pylos. The alternation between -si-ja and -ti-ja must be owed to analogical levelling: toponymic adjectives ending in -tios or -thios first became –sios in Mycenaean, as in Attic Μιλήσιος from Μίλητος and Προβαλίσιος from Προβάλινθος, but then the dental was often restored by analogy with the noun, as in Attic Κορίνθιος from Κόρινθος and Knossian ra-su-ti-jo /Lasunthios/ from *Λάσυνθος ‘Lasithi’106. Hence the forms ti-nwa-si-jo and ti-nwa-ti-ja-o must be derived from a place-name that is not itself attested, but was at once reconstructed as *ti-nwa-to and tentatively recognized as a prehellenic toponym in -ανθος within the wider class of such toponyms in -ανθος, -ινθος and -υνθος107. Thus the place-name *Ti-nwa-to108 should be interpreted as /Tinwanthos/ or /Thinwanthos/109, and the corresponding adjective as /T(h)inwansios/ or /T(h)inwanthios/. Except for pe-ru-si-nwa ‘last year’s’, no Mycenaean word containing nwa has an Indo-European etymology110.

Let us briefly examine the pre-hellenic words in -ανθος111. The termination shows that the mountain-range Ἐρύμανθος or Ἐρυμάνθιον, now the Olonós on the north-west border of Arcadia, has a pre-hellenic name, as many mountains do. A settlement Ἐρύμανθος is said to have been the earliest name for Psophis, and the river Ἐρύμανθος flowed south-west from the mountains to join the Alpheus112. On Pylos tablet Cn 3.6 a contingent of U-ru-pi-ja-jo, a detachment of troops who were defending the coast and were stationed at O-ru-ma-to in the Hither Province, send an ox to Diwyeus, one of the officials called ‘Followers’ that liaised with the coastguard113. These same U-ru-pi-ja-jo, noted to be thirty in number, are described by the ethnic O-ru-ma-si-jo-jo on ‘coastguard’ tablet An 519114; this ethnic gives the place where they were based, whereas they are guarding the coast at a place called A2-te-po south of Ro-o-wa, which was also in the Hither Province115. The fact that the ethnic of O-ru-ma-to is O-ru-ma-si-jo, just as that of *Ti-nwa-to is Ti-nwa-si-jo, confirms that O-ru-ma-to ended in -ανθος.

O-ru-ma-to must be the same word as Ἐρύμανθος, with a different initial vowel, because the same fluctuation is seen in other words that appear to contain the same stem: the name of the Homeric warrior Ἐρύμας is read as Ὀρύμας by the T scholia116, and the toponym Ἔρυμνα in Pamphylia was also known as Ὄρυμνα117. But the coincidence does not prove that Pylian O-ru-ma-to was located near Mt Erymanthus118; on the contrary, the corresponding reference to O-ru-ma-to in the coastguard tablets appears between entries pertaining to contingents in the south of the Hither Province, between Ro-o-wa and Pi-ru-te119. Another name in -ανθος in the archive is Pu-ro Ra-wa-ra-ti-jo (Ra-u-ra-ti-jo), i.e. /Pulos Lauranthios/, on Pylos tablets Ad 664 and Cn 45120, which is apparently formed from *Lauranthos121. This town lay in the south-east quadrant of the Further Province122. The only place outside the Western Peloponnese that ends in -ανθος is the village of Πύρανθος near Gortyn in Crete, modern Pyrathi123. However, like the name Gortys or Gortyn, the name Pyranthos could of course have been taken from the Peloponnese to Crete, since Arcadian elements appear in the dialect of central Crete at Axos and Eleutherna.124 With Pyranthos compare Hittite Puranda, a village in Pisidia125.

The concentration of place-names in -ανθος in the Western Peloponnese suggests that *Ti-nwa-to was located there. The likeliest explanation for the limited distribution of such names is that the local dialect of the pre-hellenic language (and this dialect alone) either modified the vowel that precedes the ending or preserved its original vocalization. In the latter case this ending is more closely comparable to the ending -anda that is so widely attested in the ancient place-names of Western Anatolia126.

4. The people of *Ti-nwa-to at Pylos and Knossos

The socio-economic status of *Ti-nwa-to and its inhabitants within the kingdom of Pylos has not been investigated, but turns out to have been peculiar.

*Ti-nwa-to was not among the sixteen major towns of the kingdom; only its ethnic attests its existence. At least two men identified by the ethnic Ti-nwa-si-jo were members of the Pylian élite. First, on tablet Fn 324.12 a certain A-ta-o Ti-nwa-si-jo, probably /Antāos/, receives an allocation of barley, perhaps in order to attend a religious festival127. On Jn 431.23 a man named A-ta-o is identified as a bronze-smith with no allotment of bronze, on An 340 a certain A-ta-o contributes or controls fourteen men, and on Vn 1191 the name appears in the genitive as A-ta-o-jo. Some or all of these further references may be to the same person, but this is uncertain128. As there was a man named A-ta-o at Knossos also (L 698), the name may have been common.

Secondly, a holding of land belonging to Ti-nwa-si-jo, which means ‘man’ or ‘men’ of *Ti-nwa-to, is recorded in tablet Ea 810129. The word may well be a name, since a singular proper name is expected here130. If, however, the name was used as an ethnic to describe an important individual from the town, it may describe the A-ta-o of Fn 324, the ‘governor’ Te-po-se-u (see below)131, or a third unidentified person132.

Thirdly, *Ti-nwa-to had a local leader or ‘governor’ (ko-re-te), whose name was Te-po-se-u. That a place which was not among the sixteen tax districts should have a ‘governor’ is not unparalleled; tablet Nn 831 mentions a ko-re-te who was probably in charge of the town of Korinthos133. Te-po-se-u appears twice. On tablet Jo 438, he is required to contribute towards the 5–6 kg of gold that the palace wished to collect for some purpose134. With ten others he is assessed for the standard amount of 250 g, the second-largest quantity listed, twice as much as the amounts for seven major towns. His gold never reached the palace, since there is no check-mark against his entry. His name recurs without a title or ethnic in tablet On 300, which records distributions or contributions135 of commodity *154, probably leather hides, among the governors of all the towns in both Provinces. Because the title ‘governor’ is given in eleven of the thirteen surviving entries, we can be sure that the same man is meant. His amount is the standard 3 units (the largest quantity is 6).

Chadwick well interpreted Te-po-se-u as /Thelphōseus/, comparing the toponym Τέλφουσα or Θέλπουσα;136 more precisely, Te-po-se-u would have been /Thelphonseus/ in Mycenaean Greek.137 This name certainly comes from the toponym Thelpousa or Telphousa; both forms are derived from *Θέλφονσα < *Θέλφοντyα ‘Place of diggings’138, with different dissimilations of the aspirates according to Grassmann’s Law139. The first is the spring Telphousa near Haliartus in Boeotia140. Ιn addition, a town of this name was located on the river Ladon in N.W. Arcadia141, but its location may have moved since Mycenaean times, since many Pylian place-names appear in Arcadia142; I suspect that they were taken thither by refugees from the collapse of the Pylian kingdom, since the Mycenaean dialect of the tablets survived in Arcadia into the historical period. In classical times two other place-names from Mycenaean Pylos are found in N.W. Arcadia—Erymanthus and Lousoi (see §5 below). In addition, Pausanias records that a river Ἁλοῦς flowed below Thelpousa143, whereas the coastguard tablets mention a place A2-ru-wo-te /Halwons/, i.e. Ἁλοῦς, in the north of Hither Province near Ku-pa-ri-so and O-wi-to-no144. Since the river’s name, from *ἁλόϝεντ-ς, means ‘salty’145, the Pylian location on the coast was probably the original one.

In addition, the lists of personnel who worked for the palace suggest that nine of its women were dependent on it and are recorded among sets of tablets that otherwise tally slaves. The Ad series records the children of about 750 women at Pylos who were working in various humble professions146. Tablet Ad 684 lists the seven children, two adult and two under age, of weavers from *Ti-nwa-to147. The same women, stated to be nine in number, reappear in tablets Aa 699148 and Ab 190149, where they have seven and three children respectively. The other groups of women at Pylos in these three sets of tablets, Aa, Ab and Ad, are identified either by their professions alone, or by toponyms, and their husbands are never referred to150. Where the toponyms can plausibly be identified, as most of them have been, they are almost all located far away on the coasts and islands of the Aegean151, as if they were captured in the kind of piracy or raiding that forms the background to Homer’s Iliad. The women in these series include women of Cythera (ku-te-ra3)152, Carystus (ka-ru-ti-je-ja)153, the Euripus (e-wi-ri-pi-ja)154, Chios (?) (ki-si-wi-ja)155, Asia/Aššuwa (A-*64-ja = A-swi-ja)156, Lemnos (ra-mi-ni-ja)157, Miletus (mi-ra-ti-ja)158, Cnidus (ki-ni-di-ja)159, and Halicarnassus (?) (Ze-pu2-ra3)160, alongside the unplaced ko-ro-ki-ja161 and Ti-nwa-si-ja162. This pattern immediately suggested that they had come to the palace as slaves, especially since they seem to have no husbands163. Chadwick proposed that they were named after the slave-markets in which they were purchased164, like the one on Lemnos in which Priam’s son Lycaon was sold165. However, historical parallels for such a nomenclature are lacking; they ought to have been known by their ethnic origins, like the Carian or Phrygian slaves of classical antiquity. Some are probably called ‘captives’: on tablets Aa 807 and Ad 686 twenty-six or twenty-eight of these women are described as ra-wi-ja-ja /lāwiaiai/, which is more likely to mean ‘captives’, from λεία (Ionic ληΐη, Doric λαΐα) ‘booty’166, than ‘harvesters’ from λήϊον ‘harvest’167. The fact that these women are explicitly called ‘captives’ might imply that the others were not, but more probably means that their ethnic origins were mixed or unknown. In any case, the others were treated like them168.

That women from *Ti-nwa-to are among these alien women is a remarkable oddity that ought to have been noticed long ago. Tritsch did so notice it, and deduced from it that the women in these documents cannot have been slaves or captives: ‘the Ti-nwa-si-ja cannot possibly be captives, for they come from a Pylian township . . . whose ko-re-te brings a gold tribute about twice as large as those of the ko-re-te of Rouso, Pakijana, Akerewa, Karadoro, Timitija, Iterewa, Eree, etc.’169. Tritsch held that the women of *Ti-nwa-to cannot represent a population cleared out of their town by the Pylian king himself170: ‘the Pylian fleet, however large, did not aimlessly raid Pylian townships to bring Pylians as captives to Pylos’171. To our way of thinking, if these women came from within the kingdom they certainly should not have been slaves. However, at Od. 4. 174–7 Menelaus tells his guests that he had thought of ‘sacking a city’ (πόλιν ἐξαλαπάξας) of people ‘in Argos’ (ἐν Ἄργεϊ) who ‘dwell round about, and are ruled by me’ (περιναιετάουσιν, ἀνάσσονται δ’ ἐμοὶ αὐτῷ), in order to hand it over to his foreign ally Odysseus and all his retinue; evidently he did not actually do so. Yet, although we do not know whether actual Mycenaean kings ever behaved so ruthlessly towards their own subjects, we cannot exclude it.

Instead Tritsch suggested that all these women were refugees or persons displaced by recent disturbances, who had fled from more exposed places in or beyond the kingdom and were gradually being found employment under emergency conditions within the palatial system shortly before the palace at Pylos was itself burned172. Such a situation existed at contemporary Ugarit, where women of Alašia (now proved to be Cyprus or in Cyprus, and at the time allied to the king of Ugarit) were taken in as refugees before that city too was destroyed173, apparently by an attack of the ‘Šikalayu who dwell on ships’174. This hypothesis has been rejected on the basis that there was no disorder in the Aegean at this time175 (this begs the question), that the terminology for the textile-workers is the same as at Knossos, where no state of emergency is documented, that these records cover more than twelve months, and that the women ought to have been dispersed for their safety176. Can this possibility be excluded?

The women of *Ti-nwa-to are exceptional in that they not only come from within the kingdom, but also have husbands. The scribe of Ad 684 adds on the edge that their children were ‘sons of the rowers at A-pu-ne-we’, a port in the Hither Province177. Chadwick called this addition ‘very remarkable, as being the only instance where the fathers of the children are mentioned’178. That the women and children were not living with their husbands confirms their humble status179, but their husbands’ existence was acknowledged by the palace in this afterthought, and suggests that the women did not have exactly the same status as other female workers employed by it. The sons of some of the other women were also rowers: thus forty men from the port Da-mi-ni-ja in the Further Province are listed as Da-mi-ni-jo among the rowers on An 610.13, and Ad 697 records ‘at Da-mi-ni-ja the sons of the linen-workers, being (?) rowers’180. If any of these women were displaced persons rather than slaves, it is the women of *Ti-nwa-to, since they, alone among such women, are recorded to have had husbands as well as sons. These men were serving as rowers at A-pu-ne-we; seven men were sent from A-po-ne-we, which is the same port, to Pleuron in tablet An 12, and An 19 lists thirty-seven rowers there. Can it be coincidence that the latter tablet includes men called po-si-ke-te-re ‘suppliants’, ’refugees’ or ’immigrants’, beside za-ku-si-jo ’Zacynthians’, ki-ti-ta’settlers’, and me-ta-ki-ti-ta ’new settlers’, who held land in exchange for service in the fleet181? There is no indication, however, that the rowers who were married to the women of *Ti-nwa-to owned any land182.

In the kingdom of Knossos women from a place called Ti-wa-to are listed among over a thousand female workers in the textile industry who were dependent on the palace. Tablet Ap 618 tallies five or more Ti-wa-ti-ja183. I suggest that Ti-wa-ti-ja may be a graphic variant of Ti-nwa-ti-ja /Tinwanthiai/, which is of course a variant of Ti-nwa-si-ja /Tinwansiai/ (above, §3); the n at the end of the first syllable would be omitted in accord with the usual orthographic conventions of Linear B, in which the sign nwa is exceptional184. Such is the length of the sign-group that a coincidence seems unlikely185. These women belong to, or are attributed to, two powerful members of the palatial élite, /Anorquhontās/ and /Komāwens/ (both often appear in the main archive from Knossos)186, together with a certain We-ra-to187. They are stationed at an otherwise unrecorded place called A-*79188. The tablet adds that two further women, who bear the names I-ta-mo and Ki-nu-qa189, are missing (/apeassai/) from two places that are familiar from the archive, Do-ti-ja and *56-ko-we190. Like the Pylian weavers from *Ti-nwa-to, they manufactured textiles191. Their status as corvée labourers, refugees, or slaves is clear.

To explain why women of *Ti-(n)wa-to are recorded in the main Knossian archive one might suggest that there was another place called Ti-(n)wa-to, not the one referred to in the Pylian archive. Normally one would not want to multiply entities unnecessarily. However, many prehellenic place-names recur in different regions of Greece, such as Leuktron and Orchomenos in Arcadia and Boeotia, Thebai in Boeotia and Phthiotis, or Korinthos in the Further Province and on the Isthmus192; so there could have been two places with this same name. However, if these women came from the Pylian *Ti-nwa-to, this would have startling implications, since the coincidence might support the latest possible dating of the main archive at Knossos, i.e. within LM IIIB. Although this dating is currently out of favour, it is yet to be decisively disproved193.

5. The location of *Ti-nwa-to

No later toponym in the Peloponnese, or indeed anywhere in Greece, corresponds to or resembles *Ti-nwa-to, whether in ancient, Medieval or modern times. Even were one attested, this would not in itself establish where *Ti-nwa-to was. Place-names often changed their location over time, above all the case of Pylos itself, which formerly lay under Mount Aigaleon (Mycenaean /Aigolaion/) at Ano Englianos, as the tablets prove, then in classical times at Coryphasium on the north side of the bay of Navarino, and now on its SE side, not to mention the traditions about other places further north in Triphylia that were also called Pylos194. Again, in classical times there was a place called Leuctrum in the Outer Mani south of Kalamata, i.e. beyond the E. boundary of the Further Province, the river Nedon, yet in the Pylian archives Re-u-ko-to-ro was a major town within the kingdom195. Again, the Ro-u-so /Lousoi/ south of Pylos in the Hither Province has the same name as classical Λουσοί in northern Arcadia east of Mount Erymanthus196. As we saw in §4, many place-names may have been taken to Arcadia by refugees from the Pylian kingdom, and there is a notable concentration of such names around Mount Erymanthus.

The geography and frontiers of the Pylian kingdom have proved surprisingly hard to reconstruct with confidence197. This is owed to two factors. First, there was a radical discontinuity in settlement at the end of the Bronze Age, when the number of settlements in Messenia declined massively198. The region changed its dialect from Mycenaean, the closest ancestor of Arcado-Cypriot, to West Greek, or Doric, a change which has seemed to many hard to explain without an influx of new people199. The discontinuity is compounded by poor sources for Messenian history in the classical period and the high proportion of Slavic toponyms200. Thus the list of nine towns in the Homeric Catalogue of Ships notoriously fails to correspond to the towns in the Pylian tablets201. and Strabo claims that Nestor’s Pylos was in Triphylia202. Secondly, the Linear B tablets were created as economic records: the network of settlements underlying them has to be deduced from their sequence in the documents, their recorded products, and the links between them, and some of these links may be hierarchical or arbitrary rather than simply geographical203. To relate them to archaeological remains on the ground, in the absence of inscriptions that tell us the names of their findspots, is even harder204.

All scholars agree that the kingdom was divided into two provinces, the Hither Province and the Further Province, by the mountains called /Aigolaion/ by the Mycenaeans and Αἰγαλέον by Strabo, and that the Hither Province lay to the west, the Further Province to the east, with its eastern border on the river Nedon205. The relative locations of places in the Hither Province close to Pylos and further south are also fairly secure, since it is agreed that they are listed from north to south206. However, the location of the northern border of the Hither Province seems less certain: did it lay in the Soulima (Kyparissia) valley, or on the river Neda, or yet much further north on the river Alpheus207?

Two main arguments have been advanced for restricting the Pylian kingdom to Messenia. First, for security and ease of communications its capital ought to have been centrally located; however, one may contrast, for instance, Britain, France, Germany, Russia, or the United States)208. Secondly, few Late Mycenaean settlements are known between the Soulima valley and the Alpheus, with a particularly noticeable gap at the Neda; however, this is an argumentum e silentio, since Triphylia is not well explored209. The best evidence for the river Neda is that the commander of the northernmost command on the ‘coastguard’ tablets (the An series) is named Ne-da-wa-ta /Nedwātās/, a name formed from ‘Neda’210. But even the first securely located place in the north-south series of towns in the Hither Province, ku-pa-ri-so (PY Na 514), which is thought to correspond to modern Kyparissia, refers to a tree that must have been very common in the landscape; therefore its location does not seem secure211. The northernmost town in the Hither Province, ?? Pi-*82, may have been inland; it does not appear on the ‘coastguard’ tablets, what that fact is worth. If Pi-*82 is to be read Pi-swa212, as is likely, its name is ‘Pisa’ like the later Pisa near Olympia on the Alpheus; its products, sheep and flax, might suit the latter location213, but these products were widespread in Mycenaean Messenia too. The second town in the Hither Province, Me-ta-pa, was on the coast214 and rich in barley and textile production215; on tablet Cn 595 it is next to a place Ne-de-we-e, which is properly linked with the name of the River Neda and likely to be near it216. Both centres controlled sizable territories217. Me-ta-pa reappears as the name of an otherwise unknown town called Metapa that is attested by a treaty of the early 5th century BC, found at Olympia, between τὸς Ἀναίτ[ς] καὶ τὸ[ς] Μεταπίς218. Since this pact is in Elean dialect and officials at Olympia were to oversee it, like the treaty between the Eleans and their neighbours the Ἐϝαοῖοι219, this Metapa was not the town of the same name in Acarnania220 but must have been in the western Peloponnese. Classical Metapa was, perhaps, south of classical Pisa221. The coincidence that Pisa and Metapa were located near to each other in the classical period reduces the odds that their collocation in the tablets is random, and makes it possible that these place-names were in much the same area in Mycenaean times, or that they were both taken to Elis by refugees from the same region in the Pylian kingdom. Dyczek puts Bronze Age Metapa at Kato Samikon, and Lukermann and Eder locate it at or near Kakovatos222. However, most scholars continue to locate Mycenaean Pisa and Metapa south of the River Neda223. We shall shortly see that Metapa also had ties to the North West sector of the Further Province.

Tritsch held that *Ti-nwa-to lay in the Further Province, probably on the Messenian Gulf rather than inland on the Laconian border224. Chadwick supposed that it was not fully part of the Pylian state, but ‘a distant possession (colony or island?) which was administratively attached to the Further Province’225. He later rejected the idea that it was an island: ‘it must have been of some size, since its assessment for gold on Jo 438 is one of the higher ones on the list. There are only two islands within easy reach of Pylos which are large enough, Zakynthos and Kythera, both of which appear to be mentioned on the tablets under these names’226. Deriving *Ti-nwa-to from *στενϝός, he suggested instead that it was in ‘the hill country immediately to the north of the Messenian valley’, i.e. above the Stenyclarus plain227; whatever the merits of this location, the proposed etymology is unconvincing228. Finally, evidently still perplexed, he proposed that it was in a part of the Mani, i.e. the east coast of the Messenian Gulf, that was not accessible by land from the kingdom’s eastern frontier229. Thus Agamemnon offered Achilles as a dowry seven towns in a peripheral area outside the kingdom of Nestor in the Outer Mani, i.e. the east coast of the Messenian Gulf230. This region was hard to reach overland from Kalamata until a generation ago; historically the Mani has always resisted subordination to centralizing powers. But better arguments can be made by reexamining the tablets.

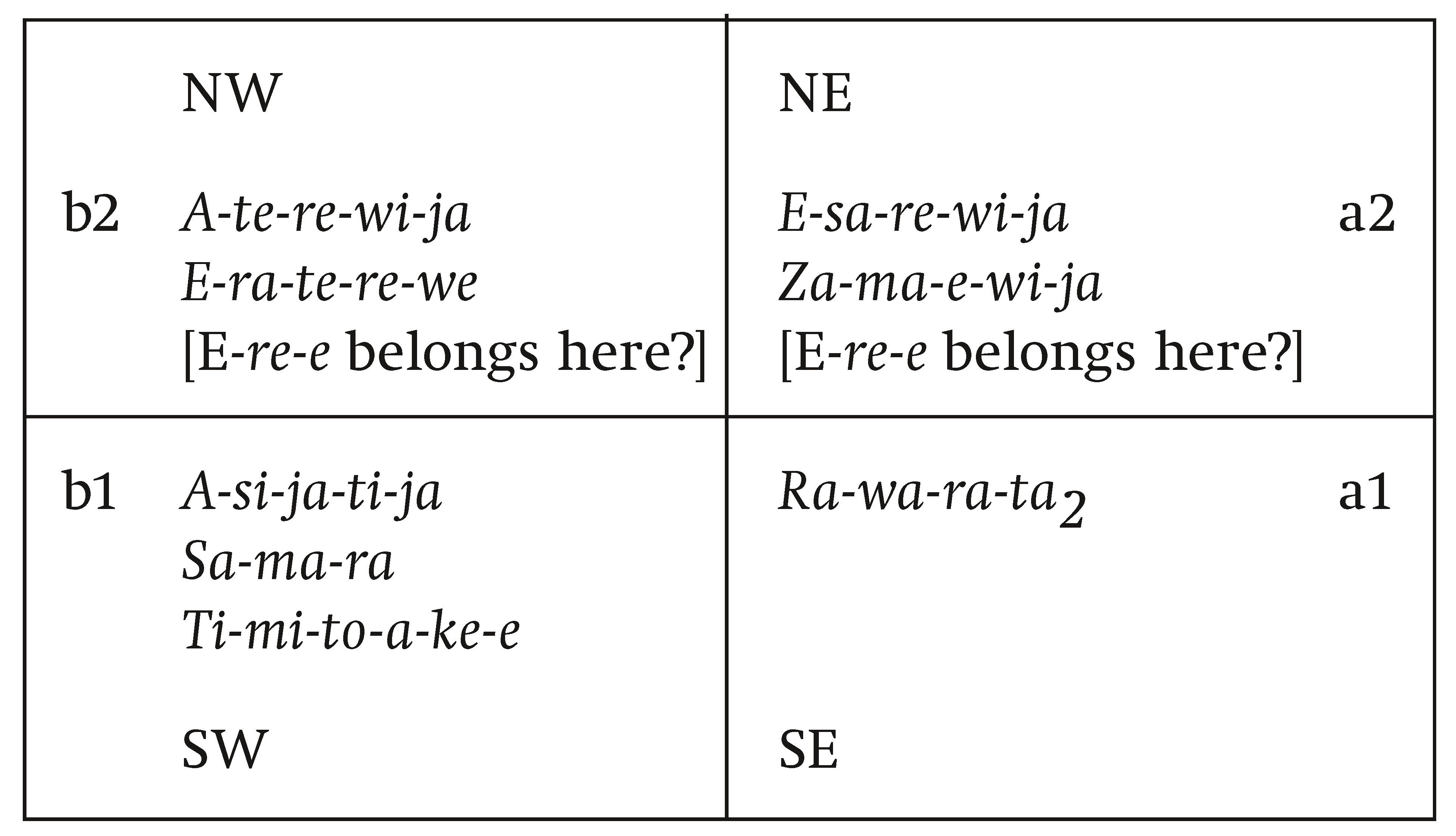

The sequence of entries in the tablets provides several clues to the location of *Ti-nwa-to. Unfortunately tablet Jo 438, recording the gold-tax on governors and vice-governors, does not itemise the towns in the usual order, and mixes up towns from the two Provinces231. It lists the governor of *Ti-nwa-to between entries for the first town from the Further Province, namely e-re-e (/Helos/ ‘marsh’), and the last town of the Hither Province, Ti-mi-ti-ja232. The location of these places depends on the organization of the four tax-districts of the Further Province in the Ma series of flax-tablets (Table 1), in which the Pamisos is the north-south division, and the Skala hills the east-west233.

Thus Jo 438 mentions the governor of *Ti-nwa-to between tax districts b1 and a2 of Table 1. This is puzzling, since in the standard reconstruction these districts are not adjacent. Ti-mi-ti-ja or Te-mi-ti-ja (/Terminthia/?) is the same as Ti-mi-to-a-ke-e, i.e. /Tirminthōn ankos/ ‘glen of terebinth trees’234, a coastal town on the western border of the Further Province; it has often been identified with the major settlement at Nichoria (Rizomylo)235, Chadwick showed that, since on tablet Cn 595 sheep from the station at E-ra-te-re-wa in district b2 are recorded as at Metapa in the north of the Hither Province, districts b2 and a2 are likely to be in northern rather than southern Messenia. Hence Za-ma-e-wi-ja and the other towns in its district are in the N.E. quadrant of the Province. Helos is listed after Za-ma-e-wi-ja on tablet Jn 829; it does not appear in the Ma series, but has its place taken by E-sa-re-wi-ja, and is also likely to be in the N.E. quadrant236. There are links on tablet Aa 779 between A-te-re-wi-ja and Metapa, on An 830 between A-te-re-wi-ja and Pi-*82 (/Piswa/?), the northernmost town of the Hither Provice, and on Ma 225 between Pi-*82 (/Piswa/?) and Re-u-ko-to-ro /Leuktron/, an important place in the further province237. Hence Helos is split into two in the Ma texts, and may have had ties to both northern tax districts238; it was probably the marshes at the source of the River Pamisos between both districts239.

Tablet On 300, transactions involving the governors of all the towns in both Provinces in commodity *154, probably hides, is also helpful in locating *Ti-nwa-to. The name of its governor, Te-po-se-u, is the final entry, after the governors of two towns that belong to the Further Province, namely a-si-ja-ti-ja ko-re-te ‘the governor of Asiatia’ and [e-re-o du]-ma ‘the official of Helos’240. Again, exactly as on Jo 438, the entry for *Ti-nwa-to appears with that for Helos.

This seems the best clue to the location of *Ti-nwa-to. It lay inland, on or over the northern borders of the Further Province, close to Helos. Whether the kingdom’s northern frontier lay on the Alpheus, or (more probably) on the Neda itself, *Ti-nwa-to must have been located in the northernmost districts of Messenia or in what one can call southern Triphylia or south-western Arcadia.241 Although Chadwick rejected most of the suggestions for locating Pylian place-names in Arcadia, he conceded that the Pylians may have occupied ‘the extreme south-western fringe of Arcadia, so as to control the few passes leading into Messenia’242.

The interior of southern Triphylia, i.e. south-western Arcadia, was so poor that it was famous for its mercenaries in historical times243. It is so lacking in fertile land that it can hardly have been any richer in the Bronze Age. Cooper has shown that Apollo Epikourios was worshipped in Ictinus’ temple at Bassae, with all its military dedications, as god of mercenaries (ἐπίκουροι)244. Such poverty may explain why women of *Ti-nwa-to went or were taken to Pylos and perhaps to Knossos to work as weavers alongside slaves from afar.

6. From the Peloponnese to Bavaria: some hypotheses

If the amber from Bernstorf was incised with Linear B in the western Peloponnese, how did it reach Upper Bavaria, and why? Even in the Middle Bronze Age, valuable artifacts could travel vast distances245. One can only offer hypotheses, since it is not clear on what basis we could decide between them, but at least only a limited number of them are available; considering them will shed light on several aspects of Mycenaean long-distance relations. If these objects are genuinely from Mycenaean Greece, they must either have been traded by Mycenaeans, taken from them by force, or paid by them for services of some kind, the most obvious of which is service in a force of mercenaries. They could then of course have been traded great distances, as far as Bernstorf, by other intermediaries. Let us start with trade.

Vianello proposed that the amber objects from Bernstorf were tokens sent from Greece along the trade-route for amber to ask for ‘more of the same’, and that the signs (which he does not interpret) signify ‘some commercial agreement’246. Indeed, names on the inscriptions could perhaps have functioned as guides to illiterate merchants or travellers; once they went back to Greece, they could have shown the inscriptions to literate officials in order to find the place or the person that they were seeking. We simply do not know how Mycenaean trade with such remote regions operated.

The piece of gold wire found deep within the suspension-hole of Object B247, which links it with the gold treasure (see §1 above), suggests that this item was at some point worn by a member of the Mycenaean élite, presumably around the wrist like the seal seen in the fresco from the shrine of the Citadel House at Mycenae (Fig. 7)248. A young man buried in a wooden coffin in a chamber-tomb in the agora at Athens in LH IIIA1 wore an amygdaloid amber bead and a seal around his wrist249. Could the gold and amber have been insignia of office, carried by rulers or lesser officials like the ko-re-te-re to enhance their authority? We are not certain what Mycenaean symbols of royal authority looked like, but it is easy to suppose that the crown and sceptre in the Shaft Graves were such regalia250. One may compare the famous LM I seal-impression from Khania which shows a large and muscular male figure holding a staff and standing on top of a two-gated city.251 For a sceptre, such as would be borne by a σκηπτοῦχος βασιλεύς, one may compare the celebrated sceptre made of enamelled gold from Kourion in Cyprus,252 or those of gold and of ivory wrapped in gold from Shaft Grave Circle A at Mycenae.253 Amber was rare and highly prized254, no doubt for its electrical properties, which would have been considered magical, as well as for its golden colour and beauty. Could the bearded face on the ‘obverse’ of Object A even depict the ruler of *Ti-nwa-to?

A variation on trade is that these objects became obsolete for some reason and sent to remote Bernstorf as diplomatic gifts. If political reorganization or conflict led to a diminished status for *Ti-nwa-to, perhaps its precious insignia of power, if this is what the amber and golden objects were, came to need a safe and lucrative disposal. Although scholars assume that the great increase during LH IIIA–IIIB1 in the size and number of settlements in the central regions of Mycenaean Greece indicates a time of general peace, archaeological and textual evidence points to the expansion of the kingdom of Pylos in LH IIIA2 and trouble in peripheral areas255. A strong argument has been advanced, on the basis of both archaeological indications and internal evidence from the Pylian archives, that the Further Province was brought into the kingdom during LH IIIA2; Bennet dates its incorporation to between 1350 and 1300 BC256. The fresco from the megaron of Mycenaean warriors by a river fighting rustics clad in hides and armed only with daggers may depict such a conflict257. The authorities at Pylos could have converted the royal insignia of the subjected town of *Ti-nwa-to into material for a diplomatic gift-exchange and sent them, directly or indirectly, to remote trading-partners in contemporary Germany.

For such a scenario one may compare the collection of gems and cylinder-seals made of Afghan lapis lazuli which were found in a LH IIIB context at Thebes in the so-called Treasure Room on the Kadmeia Hill, where they had ended up as raw material in a Mycenaean palatial workshop258. The latest of the numerous Kassite seals from Babylon, some with dedications to Marduk, date stylistically from c. 1250 BC. Porada proposed that this cache was a diplomatic gift to the Thebans from King Tukulti-Ninurta I of Assyria, who would have taken it from Babylon after he pillaged the temple of Marduk there in 1225 BC259. This hoard, which included numerous heirlooms, would have had high value to the Assyrians. However, the seals were no longer usable for their initial purpose; the Assyrian king had nullified their utility as sources of power, and it became convenient, or even wise and necessary, to dispose of them safely as scrap. The solution adopted was to send them far away, presumably as part of a mercantile exchange so that no loss was incurred. If it were doubted whether the Assyrians would have wanted to establish a close relationship with Mycenaean Thebes by sending such an expensive gift260, one must remember the Hittites’ determination, expressed in the treaty between Tudḫaliya IV of Hatti and Šaušgamuwa of Amurru in Syria, to interdict trade between Tukulti-Ninurta I and the land of Aḫḫiyawa.261

Let us turn to the second possibility, that these materials were seized by force. The gold treasure represents about 46% by weight of the 250 g which, according to tablet Jo 438, the governor of *Ti-nwa-to was expected to send to the palace, but which did not arrive there in time to be recorded before the palace was destroyed (see §4). Were the treasures from Bernstorf that very same consignment, with the amber meant to make up the rest of the payment, seized during the catastrophe of c.1190 BC and then taken, either directly or indirectly, to Bavaria? This scenario would be part of a pattern of contacts between western Greece, Italy and the Adriatic that manifested itself from LH IIIB2 onwards in such phenomena as Naue II swords and fibulae262. That would entail that the enceinte at Bernstorf was burned far later than in c.1300, as archaeologists believe it was (see §1). But these materials could have been seized at some earlier date, perhaps in LH IIIA 2 when the Pylian kingdom was expanding263.

A final option is that these materials were brought to Bernstorf, whether directly or indirectly, after they had been paid to (or taken by) mercenaries in the service of the palace. Such warriors could carry treasures great distances, like the gold and ivory sword-hilt brought to Lesbos by the poet Alcaeus’ brother Antimenidas after he had served in Judaea under the Babylonians264. Chadwick already proposed that the Pylian levies of gold recorded on tablet Jo 438 were needed for buying off hostile forces or paying mercenaries265. Mycenaean warriors were depicted far away, both in Anatolia at Boğazköy and in Egypt at El Amarna266. Like their Near Eastern counterparts, the rulers of Pylos and Knossos both employed such forces267. Gschnitzer has shown that Mycenaean armies consisted of three elements: chariotry, the general levy of the /lāwos/ ‘host’, and specialized forces that were, at least originally, of foreign origin268. Driessen pointed out that contingents of such troops called Ke-ki-de, Ku-re-we (/Skurēwes/ ‘Scyrians’?)269, O-ka-ra* (o-ka-ra3) ’Oechalians’, and U-ru-pi-ja-jo* were serving at both Pylos and Knossos270. Moreover, Gschnitzer identifies the Pe-ra3-qo at Pylos as /Pe(r)raigwoi/ ‘Perraebians’ and the I-ja-wo-ne* at Knossos as /Iāwones/ ’Ionians’; neither group would have originated within their respective kingdoms271. We do not know where the other groups came from, but the various contingents of the coastguard at Pylos, collectively called e-pi-ko-wo272, are not named after the toponyms of Bronze Age Messenia. Chadwick deemed them ‘communities resident within the kingdom of Pylos but not part of the normal Greek population’, i.e. pre-hellenic subject groups273, but this does not account for the groups recorded at both Pylos and Knossos. According to the Na series of tablets, the Pylian contingents held flax-producing land and were associated with textile production274. The e-pi-ko-wo* on tablet As 4493 at Knossos, who like their Pylian counterparts appear with an e-qe-ta /hequetās/ ’follower’, were also associated with textile production275. In both kingdoms they apparently held land in exchange for military service276, like some of the rowers at Knossos and Pylos (rowers, of course, could also fight)277.

The coastguard tablets from Pylos bear the heading o-u-ru-to o-pi-a2-ra e-pi-ko-wo, i.e. /hō wruntoi opihala e-pi-ko-wo/ ‘thus the e-pi-ko-wo* are protecting the coast’278. Ever since the decipherment of Linear B, e-pi-ko-wo* has been read as ἐπίκο(ϝ)οι ‘watchers’279. The later word ἐπίκουρος, taken to mean ‘allies’ in Homer, has been derived from a cognate of Latin currō ‘run (to assist)’, from the Proto-Indo-European root *kors-280. This root, however, is otherwise unattested in Greek, and one can readily interpret e-pi-ko-wo as /epikorwoi/ ἐπίκουροι, from /korwos/ ‘boy’281. Melena proposed that e-pi-ko-wo* means ’those in charge of young apprentices’, taking the prefix epi-* as ‘over’282. However, if one understands epi- as ‘additional’ the compound would mean ‘extra lads’, i.e. ‘extra warriors’, which is perfectly acceptable in semantic terms283. Cooper proposed that the term evolved from ‘allies’ to ‘mercenaries’, which is its sense in late 5th century authors284. In fact it already means ‘mercenary’ in Archilochus285 and in the Iliad, even though the Trojans’ ἐπίκουροι are always translated ‘allies’286. However, Homeric ἐπίκουροι are clearly ‘mercenaries’ who are allies or ‘allies’ who are mercenary. Thus Hector points out to them that the Trojans’ payments of ‘gifts’ and provisions to them are excessive if they will not fight:

κέκλυτε μυρία φῦλα περικτιόνων ἐπικούρων· οὐ γὰρ ἐγὼ πληθὺν διζήμενος οὐδὲ χατίζων ἐνθάδ’ ἀφ’ ὑμετέρων πολίων ἤγειρα ἕκαστον, ἀλλ’ ἵνα μοι Τρώων ἀλόχους καὶ νήπια τέκνα προφρονέως ῥύοισθε φιλοπτολέμων ὑπ’ Ἀχαιῶν. τὰ φρονέων δώροισι κατατρύχω καὶ ἐδωδῇ λαούς, ὑμέτερον δὲ ἑκάστου θυμὸν ἀέξω.

‘Listen, you myriad tribes of allies who dwell round about: I did not gather each of you here from your cities because I needed or wanted a crowd, but for you to protect with zeal from the warlike Achaeans the Trojans’ wives and innocent children. To that end, I wear out my people with gifts and food, but nourish the pride of each one of you’287

These ἐπίκουροι ‘protect’ (ῥύοισθε) the city with exactly the same verb, wruntoi = ῥύ(ο)νται288, as on the heading of the coastguard tablets, /hō wruntoi opihala epikorwoi/. Again, Hector tells Poulydamas that they must capture the Achaeans’ ships because the city’s payments of gold and bronze have bankrupted the city:

πρὶν μὲν γὰρ Πριάμοιο πόλιν μέροπες ἄνθρωποι πάντες μυθέσκοντο πολύχρυσον πολύχαλκον· νῦν δὲ δὴ ἐξαπόλωλε δόμων κειμήλια καλά, πολλὰ δὲ δὴ Φρυγίην καὶ Μῃονίην ἐρατεινὴν κτήματα περνάμεν’ ἵκει, ἐπεὶ μέγας ὠδύσατο Ζεύς.

‘For once all articulate people used to call the city of Priam rich in gold and bronze. But now the fine heirlooms are perished from our halls; many are the possessions traded to Phrygia and lovely Maeonia, since great Zeus got angry’289

Thus ἐπίκουροι already connotes ‘mercenaries’ in the Iliad. Expeditionary troops were paid either by plundering cities, or, if they were on the defending side, by gifts of what would otherwise have been looted. Kings like Peleus and Menelaus could also give land within their kingdoms to foreign warriors like Phoenix and Odysseus, in the latter case with his retainers, in exchange for military service.290 We have seen that the situation was similar in the Bronze Age.

Thus ἐπίκουροι is the easiest interpretation of e-pi-ko-wo. Chadwick refused to interpret e-pi-ko-wo as ἐπίκουροι on the historical ground that the Mycenaeans would have been imprudent to employ alien ‘allies’ for anything but non-combatant duties291. However, the reliance of Late Bronze Age kingdoms on such troops is well documented. It was certainly imprudent if they contributed to the collapse of around 1200 BC, but imprudent actions are all too common in human history. In this case one should remember the Romano-Britons’ reliance on Germanic mercenaries for the defence of the ‘Saxon shore’ in eastern England, where these mercenaries eventually invited in their friends and relatives and took the country over292. The heading of Pylos tablet Cn 3 gives the troops of the coastguard the collective name me-za-na293, which is rightly read as /Metsānai/ ’Messenians’294. Does this not suggest that these warriors took control of the region after the fall of the palace and gave their name to it? This was certainly done by the Franks, who gave their name but not their language to France, and the Huns and Bulgars who did likewise to Hungary and Bulgaria. We should be alert to such possibilities.

As we saw in §5 above, *Ti-nwa-to was in southern Triphylia or south-western Arcadia, a region famous for mercenaries in historical times295. Such a location for *Ti-nwa-to is also attractive because it was rich in gold and amber—but not, of course, because these substances occurred there naturally. Large amounts of Baltic amber, as well as gold, appear in the tholos tombs at Pylos, Routsi (Myrsinochori), Koukounara, Peristeria, and above all Kakovatos, down to LH IIB296. The heyday of the traffic in amber was in LH I–IIA (as well as later, from c. 1200 BC onwards)297. It percolated through Mycenaean society more widely, but in smaller quantities, during LH IIIA–B; there is none from the Palace of Nestor298. Although some amber was still being traded by sea in c. 1305, since at least forty beads of Mycenaean type made of Baltic amber were recovered from the shipwreck at Uluburun299, it has been suggested that this was simply by a redistribution of the plenteous supplies which had arrived in Early Mycenaean times300. The tholos tombs at Kakovatos were extremely rich in both gold and amber, and surely some of them had already been robbed of their wealth by Late Mycenaean times.

The whole story may never be known, but the discovery of Linear B in Upper Bavaria opens a surprising new window onto the Mycenaeans and their far-flung connections.

7. Appendix: the Inscription on Object A

The text on Object A was assigned the number BE Zg 1. It is very obscure, since two of its three signs are unclear (Fig. 4), and there are high odds against achieving an assured interpretation of even two signs without a context.

The first sign | or ↾ looks like an upright arrow or spear with something of a point at the top, like the ideogram ? has ‘spear’ but with a different orientation. This upright can hardly be a word-divider, since it is too tall and redundant in the absence of a second sign-group. Might it be represent a sceptre, conceivably as a symbol of sovereignty or rank? We can compare the gold-wrapped wooden sceptre from Bernstorf: just as Object B seems to bear a representation of the crown with its five projections, so too Object A may represent the sceptre that was found with the crown. Thus this seems the best interpretation of this sign.

The second sign is the familiar wheel ? ka. One may also compare the ideogram ? rota.

The third sign  consists of a square, occupying the upper half of the sign, that is bisected by a single central vertical line which runs from the very top right down to the base-line, like the ideogram ? gra ’wheat’ but with straight sides. It is not ? wa, where the lateral verticals always continue to the bottom and the box is not bisected. The sign ? ko is once written φ by the scribe from wa-to in Crete who painted some stirrup-jars found at Thebes301, but this cannot be relevant, since our scribe could draw curves. The sign ? a2 always has distinct curves or, as in Hand 1 at Pylos, angles, and is never simplified to a box bisected by a vertical line. The Bernstorf sign does not correspond to ? a, even though many variants of this have a second horizontal above the first one, since in ? a the space between these horizontals is never bisected by the upright. It does correspond to the rare variant of the sign ? di which has a medial cross-bar in Hand 91 at Pylos302. In addition, the sign ? ne is very similar in Hand 11 at Pylos, but still has distinct curves to the side-bars that the Bernstorf sign lacks.

consists of a square, occupying the upper half of the sign, that is bisected by a single central vertical line which runs from the very top right down to the base-line, like the ideogram ? gra ’wheat’ but with straight sides. It is not ? wa, where the lateral verticals always continue to the bottom and the box is not bisected. The sign ? ko is once written φ by the scribe from wa-to in Crete who painted some stirrup-jars found at Thebes301, but this cannot be relevant, since our scribe could draw curves. The sign ? a2 always has distinct curves or, as in Hand 1 at Pylos, angles, and is never simplified to a box bisected by a vertical line. The Bernstorf sign does not correspond to ? a, even though many variants of this have a second horizontal above the first one, since in ? a the space between these horizontals is never bisected by the upright. It does correspond to the rare variant of the sign ? di which has a medial cross-bar in Hand 91 at Pylos302. In addition, the sign ? ne is very similar in Hand 11 at Pylos, but still has distinct curves to the side-bars that the Bernstorf sign lacks.

Its discoverer, Manfred Moosauer,303 read the inscription from left to right as ??? do-ka-me, but this does not seem likely. Olivier suggested ?? ka-a304, but the ? a would have had to be very badly written. The reading could be ?? ka-di, but the sign-group is unparalleled in Linear B305. If this inscription too is dextroverse, it might read ?? di-ka; the closest parallel in Linear B is Mount Dicte in Crete (di-ka-ta)306, but the match is poor. If the reading were ?? a-ka, there is an obscure place called a-ka in the Knossos sheep tablets307, or the name /Arkas/ Ἀρκάς, the mythical founder of Arcadia, might be read. None of this is very convincing, and I suspect that the scribe was simply not very literate, which would not be so surprising if *Ti-nwa-to lay on the periphery of the Pylian kingdom, perhaps indeed in what was later called Arcadia.